Environment

Alternate Visions of Motherhood

A Personal Perspective: What myths and science tell us about motherhood.

Posted June 29, 2022 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Ma-aaa!

In almost every language, a variation of mama is a baby’s first sound-word. And rightly so. The infant’s wail signals an urgent need, a summons to a nurturing maternal presence. To consider the cry being unanswered you must imagine a world without mothers, without nourishment, a world of unthinkable despair.

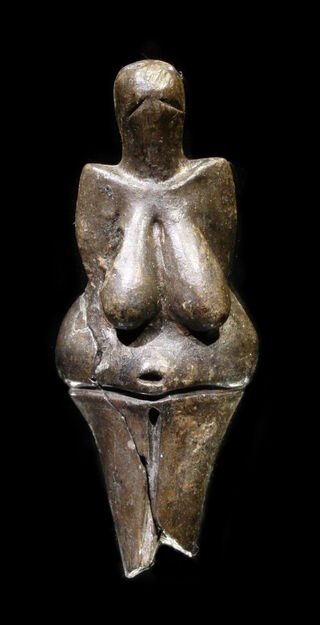

Mothers represent birth, life, sustenance, and the continuation of the species. In the symbolic world, Mother Earth embodies the mother principle. Numerous indigenous myths partner her with Father Sky. The two principles, matter and air, (matter, material from the Latin mater or mother) combine to create life. Father Sky provides sun, wind, and rain that replenish the earth, but all living things depend on the benevolent fecundity of Mother Earth to flourish and grow.

Our human roots are in the soil. Like most life forms, we spring forth from the earth and are dependent upon her for subsistence. In our conventional world, the Great Mother is not part of our daily reality. We no longer believe in the spirits of trees or the souls of animals. We know her through myths and fairy tales.

Across cultures, the Great Mother manifests in dreams and visions and artistic renderings and in inarticulate movements within our psyches that touch mind and heart.

In her idealized form, the Great Mother is a loving goddess, a good fairy or fairy godmother. She watches over us, recognizes our longings, and sends helpers. Sometimes she appears disguised as a wise old woman or kindly animal, a protective she-bear, or a lioness that pops up in a dream. All power and magic are hers; what we lack, she supplies. She sees our situation and knows our needs. We never feel abandoned. Whether we face internal or external chaos, enemies, tricksters, or evil forces, her strength, her courage, and her fortitude support our efforts. She is loyal to us. In the primitive layers of our psyches, we believe in her existence. The idealized good mother, Great Mother, is abundant Nature herself, all-giving, all-loving. She is super-human, a far cry from the flawed and fallible women who gave us birth.

In her destructive aspect, the Great Mother steals into our lives as the bad fairy; we prick our finger on a spindle and sleep for a hundred years. She is the evil stepmother disguised as a friendly apple-seller. She is the shadow side of our feminine nature, vengeful because society does not accept her ferocity, her power. She is despised or ignored. Much to society’s peril. But that is another story.

With our outer world broken and in decline, feelings of helplessness and confusion increase, and we are in need of a caring, comforting maternal guiding spirit that can offer refuge and restore our faith in our capacity to adapt and re-vision a future.

Inhabitants of the ancient Roman world looked for help from the Goddess Cura, or Care. The myth tells us about the relationship between humans and care. Human beings are the creation of Cura. Her care and devotion are her lifelong gifts. Our educated modern minds easily distinguish between the factual and the mythological, between the symbolic and the literal, and yet because the universal motifs and patterns in tales energize the unconscious layers of our psyches, we are strangely comforted by them.

However, we look to science to fortify and confirm ancient truths.

Studies in neuroscience, psychology, and sociology support what the ancients knew about our innate need for mothering. In the 1950s, American psychologist Harry Harlow’s now-classic laboratory experiments with rhesus monkeys concluded that for healthy development babies needed more than food from their mothers.1 Comfort, companionship, and love proved to be equally important for an infant’s healthy physical and mental survival. Harlow’s revolutionary experiments built on the research of psychiatrist and psychoanalyst John Bowlby2,3 who studied the effects of institutionalization on child development, especially the traumatic impact of separating infants and young children from their mothers. Their work led to a deeper investigation of parent-child bonding and encouraged a greater understanding of how infants attach to their caregivers and led to more sophisticated theories about attachment styles.

As our institutions fail and we face destructive new weather patterns and diminishing financial resources — fear, anger, and anxiety escalate. COVID, too, has altered the landscape of mothering. During periods of stress and instability, we need maternal care and comfort from those who embody a mothering presence. Overburdened and lacking government or community support, mothers and caregivers who are tasked with overseeing family life, children’s at-home education in addition to earning a decent wage are now speaking out.

I sympathize. As a young mother, I entered graduate school not knowing exactly what I’d signed up for. The decision was a life-changing event. A conflict arose between my creative and domestic selves.

The writer needed silence, solitude, and the time to explore the hidden tunnels of Self.

My role as a mother demanded opposite qualities: predictability, stability, sacrifice, and endless patience with the menial tasks of caretaking. Above all, being a mother meant I needed to provide a constant loving presence for my children. Much like pantheons of female deities that represent different archetypes in our unconscious — Aphrodite, Athena, Hera, Demeter, Artemis — I was at war with myself.

I was lost and frustrated. But today’s mothers are burdened in ways I was not: school shooters, educating children at home while working full-time. These were not a daily reality. “Pandemic” was not part of my vocabulary. Institutional safety nets allowed me to believe universal childcare and healthcare would soon be offered. I had hope. If anything, mothers earnestly believed our efforts to improve the conditions of motherhood would bear results.

A foundation of hope may be part of our survival equipment. Has hope for our future disappeared? How do we mother our families as well as the greater community when we ourselves are exhausted and depleted? How do we address empathy fatigue? What are the collective values around “good mothering”? What does it mean to be a good mother to our family? To our country and our communities?

What we seek is a model of mothering that is not confined to gender or role identity and that benefits both the individual and the community. One I’ve found that comes closest to that is set forth in a transformational book titled: Restoring the Kinship Worldview: Indigenous Voices Introduce 28 Precepts for Rebalancing Life on Planet Earth by Wahinkpe Topa (Four Arrows) and Darcia Narvaez, Ph.D. The introduction addresses the critical differences between the dominant Western anthropocentric, materialistic worldview with its emphasis on rigid hierarchies of race, class, gender, dualistic thinking, and individualism versus a worldview that acknowledges nature as sentient, benevolent, and composed of biocentric interconnected systems.

The contributors to the book call us to the maternal care of the planet and each other, prizing mutual dependence, humility, gratitude, generosity, and community welfare over competition and personal gain. Let us envision more pathways to change.

References

1 Harlow, Harry, “The Nature of Love” American Psychologist (1958) https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1960-02805-001

2 “Maternal Deprivation” Wikipedia entry on John Bowlby’s work https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maternal_deprivation

3 “Attachment Theory” Wikipedia entry on John Bowlby’s theory https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attachment_theory