Psychology

Why Science is "Mindblind," and Why We Need to Fix It

Science does not know how to talk about the mind.

Posted April 30, 2021 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Science is mindblind, meaning science does not have a general consensus on how to frame and talk about the mind.

- Mental behavior is a different kind of behavior than either physical behavior or living behavior, and it is crucial in framing the mind.

- Mental evolution is as different from biological evolution as biological evolution is from cosmic evolution.

- The Unified Theory of Knowledge shows how we can scientifically define the mind, self-consciousness, and idiographic subjectivity.

Modern science is mindblind.* By that I mean that we scientists generally do not know how to talk about “the mind” from the vantage point of science.

Evidence for this is everywhere. It is seen in the ubiquity of the so-called “mind-body problem” in philosophy, as well as “the hard problems of consciousness.” Some scientists, like Donald Hoffman, now argue that rather than energy and matter being the fundamental substances in the universe, it is consciousness. The primary reason Hoffman reaches this rather radical conclusion is that he does not think consciousness fits into the materialistic language of mainstream science. As such, he concludes that maybe a dramatic metaphysical revision in our understanding is necessary.

The problem, from the vantage point of the Unified Theory of Knowledge, is more mundane. It is that science is “mindblind.” I mean this in two senses of the word. First, the language game of modern, empirical, natural science is all about behavior and being situated in an objective stance. From this third-person position, subjective conscious experience sits across an “epistemological gap.” This is because it is impossible to directly observe another’s direct experience of being. As such, science is epistemologically blind to idiographic subjectivity.

Science is also mindblind when it comes to effectively framing the ontology of mental processes. Now, as the brilliant work of my friend and colleague John Vervaeke shows, science is not completely blind here. Indeed, we made huge strides in the 20th century with cybernetics and the cognitive revolution. And those strides are continuing with work on predictive processing by folks like Karl Friston, especially when those advances are lensed through Vervaeke's recursive relevance realization.

Broadly speaking, the cognitive revolution gave us the idea that the mind or mental processes emerge as a function of neuro-information processing in the brain. Information processing is a complicated concept, but at its base, it involves a system that takes in inputs, translates them to some kind of “computational language” that can then be recursively computed and stored, and used to generate some outputs into some other medium. This means that just as the gut metabolizes food for energy, the brain metabolizes information to predict guide overt animal behavior. This is a basic "cognitive" model of the brain and nervous system.

Despite these advances, science remains largely mindblind. In simple terms, this refers to the fact that there is no agreement about what science means by the mind. You see, the neurocognitive revolution was only one piece of the puzzle pertaining to the mind (see here). It did not really address the nature of subjective conscious experience. That is why Donald Hoffman, who was trained in computational psychology, shifted his metaphysics to a “consciousness first” approach. The neurocognitive revolution also has struggled with two other problems associated with the mind, which are the concept of the self (see here) and the nature of explicit self-conscious awareness in humans.

Many natural scientists think about the mind in terms of behavior. Behaviorists like Watson and Skinner made this move. So too do behavioral biologists, like Professor Robert Sapolsky. His book Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst is, in many ways, excellent. However, I see the world through a completely different metaphysical perspective. And no, it is not because I have some “woo” version of science that is "post-materialistic" (see, e.g., here). Rather, it is because I see what is called the Life-to-Mind joint point.

Seeing the Mind Joint Point

Early in the book, Professor Sapolsky clearly articulates the professional perspective that grounds his book: “I make my living as a combination neurobiologist—someone who studies the complexity of the brain—and a primatologist—someone who studies monkeys and apes. Therefore, this is a book rooted in science, specifically biology” (p. 4).

This sentence says it all. And it shows that, at least from the vantage point of the UTOK, Sapolsky is mindblind. You see, to my way of understanding science, primatology should not be thought of as a biological science. Instead, it should be considered part of comparative psychology and be seen as a "basic psychological science." To be fair, people have different opinions about this, and certainly many people think of primatology in terms of biology. Indeed, mine is the minority position, and Professor Sapolsky is certainly justified in his claim given current institutional identities.

However, from the vantage point of map of reality and science given by the Tree of Knowledge System, this way of thinking is grossly confused. The reason is simple. Animal behaviors such as primate aggressive actions are not just behaviors, or even biological behaviors. Properly considered, they are mental behaviors. Imagine three cats in a tree; one dead, one anesthetized, and one awake and aware. (Clearly, scientists love abusing cats in thought experiments). If you drop them, they all behave.

However, they behave very differently. The first falls through the air, lands on the ground, and bounces. Such behaviors are “physical” or “material” behaviors that are a function of gravity, the mass and shape of the cat, and things like air resistance. The second cat also falls and bounces. Same deal on the outside. However, if you look inside the second cat, you see behavior of a different kind. All of the blood flow, heart pumping, and cellular activity that maintains the cat's biological integrity are physiological behaviors. These are the behaviors of life, which is the subject matter of biology.

The final cat lands on its feet and takes off. This is behavior of a different sort. In the language of UTOK, this is mental behavior. Mental behavior is defined as the behavior of the animal as a whole mediated by the brain and nervous system that produces a functional effect on the animal environment relationship. If the cat took a swipe at its handler because it was pissed that it was dropped, that aggressive behavior would also be mental behavior. Mental behaviors are (or should be) the subject matter of basic psychology.

From this perspective, Sapolsky's book is clearly misnamed. It most definitely is not about "behavior" in general. Rather it is about a particular kind of mental behavior in humans. The misnomer arises precisely because science in general and psychology in particular has failed to clarify the relationship between behavior and mental processes. If my discipline had effectively solved this problem 100 years ago, Sapolsky would not be confused today.

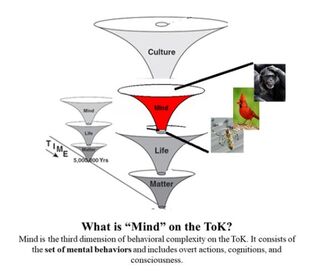

The UTOK solves science's mindblindness via three frames. First, via the Tree of Knowledge System, it highlights the fact that there is a “joint point” between the domain of living behaviors and the domain of mental behaviors. It starts with the Cambrian Explosion, which saw the evolution of animals with brains and complex bodies engaged in "mental behavior". Recent work on the ancient origins of mind and consciousness (see, e.g., here, here, here, and here) make this point clear. In the language of UTOK, this is the Mind plane of existence.

A joint point is a complexity building feedback loop that generates a new dimension or plane of existence. Behavior Investment Theory is the UTOK’s joint point between Life and Mind. Behavioral Investment Theory is metatheory that joins neurocognitive science with behavioral sciences and ethology and places them on an evolutionary foundation. It is crucial to note that many big picture scientific worldviews are completely blind to this crucial joint point in nature. This includes E O Wilson’s Conslience, David Christian’s Big History, and Holmes Rolston's The Three Big Bangs, and many others. These authors simply fail to understand that mental evolution is as different from biological evolution as biological evolution is from cosmic evolution.

The second problem that science is confused about is the self-into-human self-consciousness shift. This represents another phase shift into a new dimension of existence. This is the Animal-Mind into Culture-Person joint point. In UTOK, Justification Systems Theory maps this territory. This is the domain of language, narrative, and justification. This is the part of the human mind that allows us to reflect on aggression and decide whether it is morally justified or not.

The third problem was mentioned previously, which is that the language game of modern science is epistemologically grounded to an objective natural behavioral view of the world. That means it is blind to idiographic subjectivity. As this blog explains, the UTOK has a placeholder for the unique particular subject that the language of science is blind to. Such a placeholder is absolutely necessary to keep our metaphysics, ontology, and epistemology in order.

We need to fix science’s mindblindness. It stems from foundational gaps in the philosophical and scientific understanding of the world that was generated during the Enlightenment, and thus it is a deep and broad problem. However, a solution is at hand. By identifying the two joint points between Life and Mind and Mind and Culture, and seeing the need for a placeholder for idiographic subjectivity, the UTOK shines the light on a new way of understanding the mind that can set the stage for revitalizing the human soul and spirit in the 21st Century.

References

*It should be noted that "mindblindness" is a term from Simon Baron Cohen who generated it to describe a central feature of autism. See here for the wiki entry on this idea.