Behaviorism

Scientifically, Say "Yes" to Behavior, "No" to Physicalism

Reductive physicalism is misguided; a universal behaviorism is the way to go.

Posted November 1, 2019 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Ontology refers to what one believes is real; that is, it is one’s theory of reality. More specifically, it can be thought of as one’s philosophy of fundamental reality.

To make this concrete, I see the corner of my desk and say it is “real.” What does this mean? At a basic level of correspondence, my perception, my language, and my actions can all line up with this reality, such that if I walk by the corner of my desk, I will either pass by it or bump into it. In philosophical language, we can say that I have an ontology (a belief about reality) that states the corner of the desk is "ontically" real.

This is a start, but to move to more refined knowledge, we need to ask some questions. Although the corner of the desk is real in some ways, it can hardly be said to be foundationally real. That is, "corners" and "desks" are presumably not the foundational conceptual categories that make up reality. For example, where does the corner "end" and some other reality begin? Or consider that “deskness” is a human invention. In noting this, we can state that the corner of the desk is clearly tied to my unique, subjective way of seeing and thinking about the world. And those are not the categories that will give us a "deep ontology." For a foundational ontology, we need a frame that is more "objectively true" and much more independent of my unique subjective concerns or perceptions.

Most people educated in modern scientific knowledge will say that the desk is really made up of molecules, which are made up of atoms and other physical forces. This is a deeper physical ontology, and much of modern science can be thought of in terms of the quest for this more "foundational" ontology. It states that conventionally understood objects like desks break up into molecules, which are made up of atoms. Atoms are made up of particles like electrons and protons. Protons are made up of even more fundamental particles like quarks. It is things like quarks and electrons that are the fundamental “particles.” They exist in fundamental fields, and forces, like electromagnetism, are communicated between them. This is the "standard model" of particle physics. It is justifiably considered the foundation of our physical ontology.

A number of philosophers and scientists believe that this foundational picture is the best, most justifiable, tough-minded picture of what is “really real.” The argument is that there is one ultimate substance (energy-into-matter on a spacetime grid), and everything that is real is real in this way. And all “real” scientific causes are material and mechanistic in nature and reduce to this level.

Consider, for example, the Great Course titled: The Theory of Everything: The Quest to Explain All Reality. The course was on foundational physical theories. The title suggests that if we found the ultimate theory of quantum gravity, we would be able to then explain all reality. As a psychologist, I don't think this accurately captures all the deep philosophical and scientific issues at play. For example, I would argue that a successful theory of quantum gravity would have little impact on, say, how we "explain" depression. Hence, it doesn't really explain all reality in any meaningful way.

Yet we do see this kind of thinking pop up in the world of psychology. It is called “eliminative materialism” and related philosophies. Such approaches attempt to reduce both phenomenological experience (i.e., a toothache) and behavior (i.e., my writing this blog) to the brain and the “mechanisms” of the body. Here is one hardcore description from the vantage point of physicalism, described as "scientism." The author, Alex Rosenberg, is a physicalist philosopher describing the process of psychotherapy:

“There are also scientifically serious approaches to talk therapy … and they might work. Stranger things have happened. Scientism has no problem with the improbable, so long as it is consistent with physics. However, if talk therapy does work, it will be like this:

“Your therapist talks to you. The acoustical vibrations from your therapist’s mouth to your ear starts a chain of neurons firing in the brain. Together with circuits already set to fire in your brain, the result is some changes somewhere in your head. You may even come to have some new package of beliefs and desires, ones that make you happier and healthier. The only thing scientism insists on is those new beliefs and new desires aren’t thoughts about yourself, about your actions, or about anything. The brain can’t have thoughts about stuff ...

“There is no reason in principle why the noises that your therapists makes, or that someone else makes (your mother, for example), shouldn’t somehow change those circuits “for the better.” Some of those changes may even result in conscious introspective thoughts that seem to be about the benefits of therapy. Of course, science shows it is never that simple. It also shows that when talking cures work, they almost always do so as part of a regime that includes medicine working on the neural circuitry. The meds reach the brain by moving through the digestive system first, without passing through the ears at all.”

I would have thought this kind of physical reductionism was a joke if I have not encountered it on several occasions. Indeed, it is authored by a well-respected professor, and is an idea that pops up with some regularity. Consider that I was engaged in a conversation with a young adult who just came back from college, and I asked him what he learned. He had a taken both a neuroscience and philosophy class that were taught by folks of this ilk and he said, more or less, that he learned he “was just a bunch of chemicals.”

From the vantage point of the ToK System and larger unified paradigm, this is both tragic and absurd. It is absurd in the sense that it is self-contradictory. If all of our beliefs and desires and arguments are epiphenomenal physical excitations, then the argument that all reality is just a bunch of physical vibrations is also just that. So what is the point of making these "sounds"?

To have a clear understanding there are a couple of separate issues that need to be sorted out. One key issue that we need to be clear about is the differences between physical reductionism, emergent naturalism, and substance dualism. Substance dualism states that there are two fundamentally different kinds of things in the world. Most famously, the Cartesian split between matter and mind. Substance dualism is deeply problematic. I am not a substance dualist. I do not believe in a knowable personal God (i.e., I am not a "theist") nor supernatural souls. The ToK depicts a substance monist view; that is, reality is an unfolding wave of energy-into-matter.

The physical reductionist stops with "matter." As an emergent naturalist (see here), the ToK System posits that the universe is an unfolding of processes; that is, of object-field changes across time and complexity. In addition, the ToK depicts the fact that new emergent properties appear as the universe evolves. Not only that, but that there are some patterns of activity that result in dramatic, qualitative shifts in complexity and self-organization. These changes in activity are such that it is observationally obvious that the real patterns of behavior are qualitatively different. Organisms (Life), animals (Mind), and people (Culture) behave radically different from inanimate physical objects.

Such behaviors things do not appear via magic or some second mystical substance like Descartes thought for the human mind. Rather they appear as a function of information-communication patterns (mediated by matter) across evolutionary developmental processes. That is why the proper ontology of the universe from a ToK System perspective is an Energy-to-Matter-to-Life-to-Mind-to-Culture wave of behavioral complexity. This gives us a radically different picture than the "I am just chemicals" ontology.

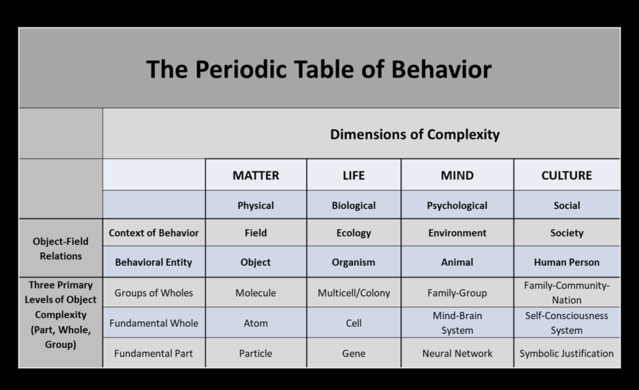

Indeed, from a ToK vantage point, a mechanistic, materialistic description of this blog in terms of "electrons" or "electromagnetic radiation" is simply nonsensical. More specifically, it is a category error (see Ryle's The Concept of Mind, for what a category error is). Instead, my writing this blog is a function of justification dyanmics at the Culture-Person plane of existence, just as was Rosenberg's ill-conceived argument about soundwaves and psychotherapy. These categories can be clearly mapped into the Periodic Table of Behavior (see also here and here), as shown here.

As a clinical psychologist who is familiar with how psychotherapy actually works, let me end with this thought: When your therapist tells you that perhaps you are seeing yourself and the world as a "bunch of chemicals" because you have been fed a misguided ideology or because you are blocking emotional wounds and engaged in the defenses of intellectualization and compartmentalization, it is highly possible that there is more to this interpretation than physical sound waves entering your inner ear.