Psychology

The Theater of Consciousness: A New Map

A new map of the theater of consciousness.

Posted March 22, 2016

This blog was authored by Mandi E. Quay, M.A., a doctoral student in health service psychology at JMU.*

As a student clinician in psychology, I am learning that a large part of my job as a therapist is to foster self-awareness in my clients. This gives rise to the question, if we are to guide our clients to become more aware, what are we trying to guide them to be aware of? One key element involves helping my clients become more aware of their conscious experiences. But what exactly do we mean by “conscious experiences”? Indeed, what is consciousness?

Until embarking upon my doctoral training, I had not really been exposed to a clear map of human consciousness. It did not show up in my undergraduate training in psychology, or in my masters training. And I don’t think it shows up in many doctoral programs in professional psychology. It seems to me that this is problematic. If most of our time as psychologists is dedicated to working with the conscious mind, isn’t it strange that an entire field dedicated to learning and knowing the human mind and mental processes cannot aptly clarify human consciousness?

In this blog, I share how I understand human consciousness. My understanding is grounded in the unified approach of my mentor, Gregg Henriques, especially his "Updated Tripartite Model of Human Consciousness". My understanding has recently increased as I have started to blend Gregg’s model with Bernie Baars’ Theater of Consciousness model. What I am trying to develop is a map of human consciousness that can function as a helpful tool not just for clinicians to navigate their clients’ internal conscious experiences, but also for anyone who wants to better understand their minds.

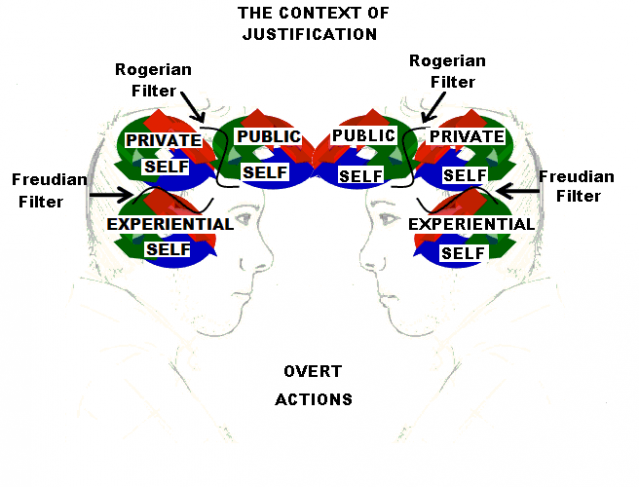

Henriques’ Updated Tripartite Model attempts to capture the key domains of consciousness, both within the self and between others. Further, it integrates important concepts from Experiential-Humanistic, Cognitive-Behavioral, and Psychodynamic theories. The basic components of this map are as follows:

- The “experiential self” is the part of your consciousness that is receiving raw sensations (both from the environment and your body), perceptual experiences, emotions, drives and imagined scenarios. Basically, this “self” comprises everything you experience in the here-and-now, “felt sense” of being. A mind-boggling part of the experiential self is that only you can ever truly know your experiential self. Nobody else will ever directly experience your first person experiences and you will never directly experience anyone else’s experiential self. No one else can see your experience of the color red!

- The “private self” is short for the private self-consciousness system. This is the self-reflective part of your consciousness where you narrate those experiences residing in your experiential self. It is the part that reflects on those sensations and emotions and tries to make sense of them based on your own personal history of experiences and your worldview. In other words, this is where your immediate experiences are being translated into linguistic representations that justify what is going on and why. This is where you might say to yourself, “Oh, this apple is the color red and I know that based on my past experiences of being told that this color is considered ‘red’ and my favorite kind of apples are red delicious.”

- The "public self" is what shared with others and is the image you attempt to project (although it might be quite different than how that image is received). The private and public self are directly connected through language because via language you are able to provide a window for others to see into your private self, which is very unique to us as human beings! So, in following the example I have been using thus far, it would be like me saying to you: “I see the color red on this apple, do you?” Now, you and I are sharing an experience together, at least through the highway that is language!

- Then there are the “filters”. You may have noticed the squiggly lines that are separating the various selves of consciousness. These are filters that regulate the flow of information between each system.

- First, there is the attentional filter, which is not labeled directly, but it comes more into focus on the next diagram. This filter determines what you become aware of (or not) in your experiential system. For instance, you are currently aware of the words you are reading on this screen, but maybe not aware of how your left big toe inside your shoe feels—until now.

- The second filter is the Freudian Filter (or the filter between the experiential and private self), which is where your private self “chooses” either what to put attention to or to suppress from your experiential system. This filter was named after Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, who noticed that we are defended against impulses and drives that we consider to be socially unacceptable. Thus, instead of experiencing them or acknowledging them, we push them back down into the depths of our unconsciousness.

- The third filter is the Rogerian Filter (or filter between the private and public self), named after Carl Rogers, the father of Humanistic Psychology, who contended that humans strive to maintain a justifiable image in the eyes of important others. Thus, this filter regulates what you share with others, usually in a way that supports an acceptable image of yourself (or what has been labeled your “persona”).

- Finally, there are two other labels on the diagram. First, “Overt Actions”, listed at the bottom, refers to observable behaviors that take place between the individuals and the environment. “The Context of Justification” refers to the relational expectations, social roles, norms, and cultural values that provide the socially constructed system that frames the exchange

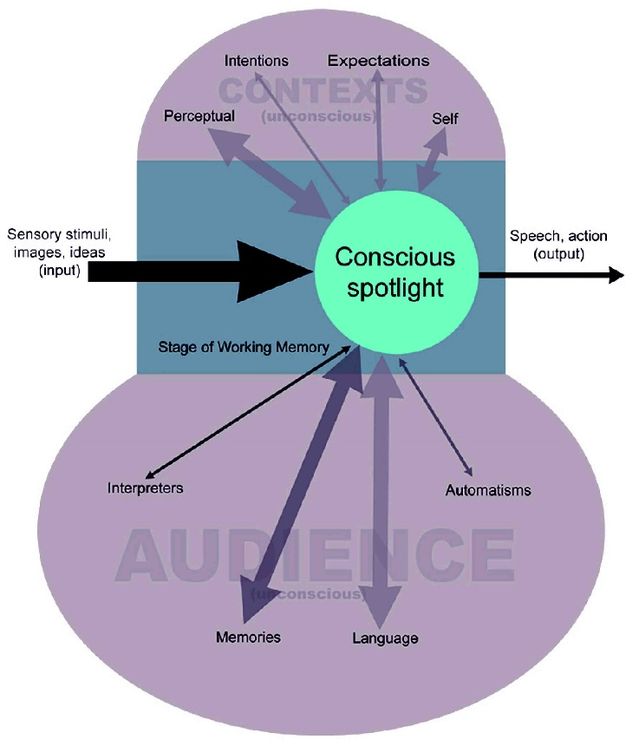

With Gregg’s framework providing a basic map of the primary domains of human consciousness, I am now going to turn to Bernie Baars’ model, delineated in his book, In the Theater of Consciousness: The Workspace of the Mind. As Baars’ notes, the idea of consciousness being akin to a theater has a long history, dating at least back to Aristotle. The idea here is that “the lights come on the stage” when you wake up and go dim when you go to sleep and flicker on and off when you dream. Baars’ combines this historical metaphor with his own approach to cognitive psychology and a “global workspace model” for consciousness, which argues that consciousness is deeply connected to working memory and provides a way to integrate, reference, and compare disparate streams of information. Here is Baars’ map of the Theater of Consciousness.

The “spotlight” refers to what is the focus of conscious attention, and it operates within the context of working memory (which is the “stage”). Everything else (i.e., sensory input, the concept of self, long-term memories, rules of grammar, automatic behaviors, etc.) is considered “unconscious”.

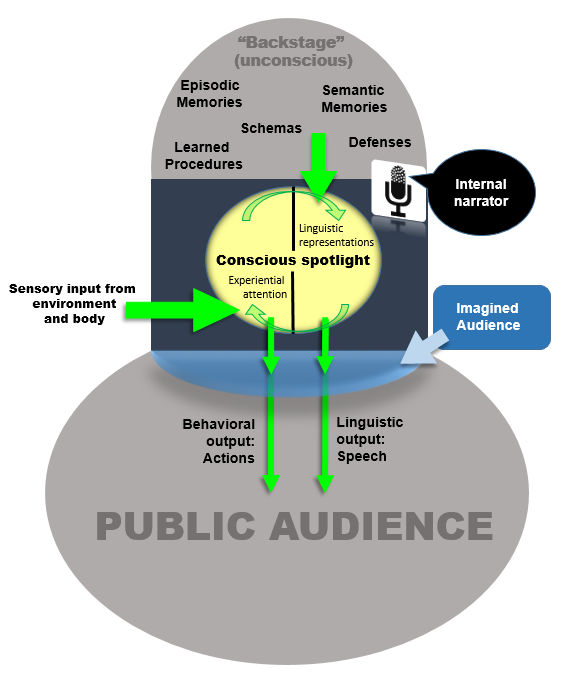

Baars’ model is valuable; however, it is missing some key pieces. Most notably, it is missing the key domains and their relationships as outlined in Henriques’ Tripartite model. So I have developed a new model combining the two. Taking the Updated Tripartite Map of Human Consciousness and applying it to Baars’ Theater of Consciousness, a new visual model is presented here.

This New Theater of Consciousness Diagram combines Henriques’ model with Baars. To the left of the model, sensory input is being received onto the stage and into the spotlight. What the attentional filter allows “on the stage” (of working memory) is denoted in our conscious spotlight. The conscious spotlight is now divided up into two streams. The left half represents the experiential information we are attending to (i.e., the experiential self); whereas the right half of the conscious spotlight are the linguistic justifications that parallel and make sense of experiences (this is one part of the private self, but not its entirety). The “public audience” is the person or people you are currently interacting with or imagining you will be interacting with in the future. It is important to reiterate that who our audience literally is and who we imagine them to be may be quite different! Who we imagine our audience to be is important because our perception of them determines what we share from our internal experiences and how we do so (i.e., the public self).

Now that we have our audience as well as our sensations, emotions, and thoughts about our immediate experiences on stage with a spotlight shining on them, we have to make sense of them somehow. This is when our “internal narrator” (the other important part of the private self) becomes a significant figure in this metaphor. The narrator is the part of our theater that is directing and further narrating the experiences in our conscious spotlight to both ourselves and to our audience. The narrator plays a role in how and what is expressed or repressed, which can be a function of our developmental experiences, who our audience is (and who we believe them to be), our tolerance of negative emotions, our ability to cope, etc. Arguably, our internal narrator plays a central role in how we relate to our experiences. For example, it is what determines if we accept or turn against our experiences.

To illustrate this, let’s use a pretty common example: Sally is naturally an anxious, temperamentally neurotic individual, as well as a high-achieving college student. One day she receives a poor grade on an exam. Her experiential self is getting panicky emotional input that causes her heart to race, her breath to become shallow, and tears to well up in her eyes. She immediately reflects on past experiences when she’s gotten bad grades where her parents expressed anger and disappointment with her. She also starts to ruminate about how this grade will result in a below average GPA and will further result in denial into graduate schools. If her internal narrator is a critical one (as is often the case), instead of allowing Sally to calmly reflect on what she has going on in her spotlight, she will instead narrate her experiences critically: “This is a mess! I can’t be feeling this!”, resulting in a frantic effort to push those emotions and memories off stage as quickly as possible. This would be unfortunate for Sally because experiential avoidance of this nature actually has a reverse effect that exacerbates the experience of negative emotions. Thus, Sally may find herself in an endless cycle of criticizing herself for her natural affective experiences and subsequently, denying herself the full spectrum of human emotion.

The Updated Tripartite Model and, as an extension, the new Theater of Consciousness has many implications for the treatment of psychological distress and discomfort, much like Sally’s. It provides a means by which clinicians and clients alike can truly come to understand the inner workings of their conscious experiences. In doing so, this gives a space for people to take a metacognitive perspective of their consciousness via a guided map that allows for a more curious, calm approach to their experiences versus a reactive, critical one. This process of awareness opens doors to experiential acceptance, which is the foundation of mindfulness. To see how this map of consciousness and its theater metaphor can be applied in the practice of mindfulness, see here and here.

__

*It is worth noting that the model described in this blog was submitted to be presented as a poster at the Eastern Psychological Association Annual Meeting, but was initially rejected because there were no “data”. I (Gregg Henriques) had to call up and have the decision reconsidered (which it was, because I am an EPA Fellow). I share this as a commentary that mainstream psychology seems often to be more concerned with data than actual understanding of the phenomena of interest.