Ethics and Morality

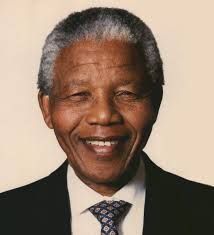

Madiba: The Gray Areas of Greatness

Does being great like Nelson Mandela always entail some badness?

Posted December 6, 2013

The historian Lord Acton wrote that ”power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely”. But his less-known, follow on sentence was: “Great men are almost always bad men.’

Did Nelson Mandela fall into Acton’s category? Clearly he was a great man, but was he also a bad man? Amnesty International could not give him their Prisoner of Conscience award in 1962—though he did receive its Ambassador of Conscience Award in 2006—because he had instigated the African National Congress into violent action as a strategy and had became leader of a terrorist group called UmKhonto we Sizwe.

This resulted in indiscriminate public bombings similar to those carried out by the IRA in Northern Ireland during the troubles, including the Church Street bombing in Johannesburg on 20 May 1983 which killed 19 people and mutilated 217 others of every race, gender and age.

What are we to make of this in the light of the global admiration for a great man following his death yesterday? Was he the saint he is being portrayed as, or was Lord Acton right in saying that greatness entails badness?

I think the problem here is the language we use to categorize individuals as if they are like whales swimming an ocean, each easily classified as black or white, big or small, weak or strong.

In fact, the brains which underlie our individuality are more akin to swarms of jellyfish, drifting on tides and currents over which they have little control, and subject to division and scattering at the whim of the sea. And as this happens, essentially we become different people.

Greatness, I would argue, comes when an individual manages somehow to harness the jellyfish brain to make a decision or takes an action that defies the direction of the tide. Through acting, the person is changed into a different person—into a different formation of jellyfish—but perhaps with a greater shape to it, or a changed direction.

I remember asking a friend and colleague who is a very experienced psychotherapist whether she thought that she had ever damaged any of her patients during her therapy. Without reflection, and with more than a touch of prickliness, she responded “no, of course not."

I was rather shocked by her answer, even dismayed. If something is powerful enough to do good, then inevitably it must occasionally harm also. No-one is perfect, mistakes must always happen. What surgeon can claim never to have damaged a patient by a surgical error?

I can think of cases where the decisions I took as a clinical psychologist were damaging to my patients. What shocked me about my colleague’s response was her ego-protective, almost visceral, response to preserve her sense of “goodness” and competence.

I know that not being able to “get over” her own ego distorted her relationships with patients and I know that this diluted the good she could do to many as well as blind her to the inevitable bad that she inadvertently inflicted on a few.

Of course Nelson Mandela did bad things but describing him as a ‘bad man’ in Lord Acton’s terms does not really make sense because Nelson Mandela is only in name the same man as the one who was sentenced on the 12 June 1964 to life imprisonment.

Most of the cells in his body were replaced several times over, and the 100 trillion synapses – meeting points between two brain cells - were in constant turmoil and flux throughout his life.

So of course, in some sense of the word, Nelson Mandela was a “bad man,” just as he was a good—a great—man also. Human beings are in a state of constant biological and psychological change and such is the complexity of our brains and our social networks that we can never avoid doing bad, some of us more than others.

The bigger the decisions we take, the greater the chance that we may do great bad as well as great good—this is the rough calculus of greatness—and in that sense Lord Acton was right.

What for me most makes Mandela such a great man is how he managed to steer his jellyfish against one of the strongest tides in the psychological ocean—bitterness at wrongs done to a person and the resulting visceral desire for revenge.

Defence of the ego lies behind such bitterness and defending the ego has caused more harm and badness in the world than almost anything else.

Nelson Mandela taught the world that it is possible to transcend the ego and achieve a kind of liberation from the prison of self. In doing this, he transmuted into a different creature, definitely great and mostly good: things are simply too complex for there never to be any bad.

Like this? Buy my book The Winner Effect