Addiction

An Anti-Drinking Drug May Hold the Cure to Sex Addiction

The opioid antagonist treats the root of addictions.

Posted September 21, 2015 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Multiple studies suggest that behind every addiction, behavioral or otherwise, lies a malfunctioning reward center.

- Naltrexone is used to treat alcohol addiction and has been found to suppress abnormal sexual behavior due to its effect on dopamine.

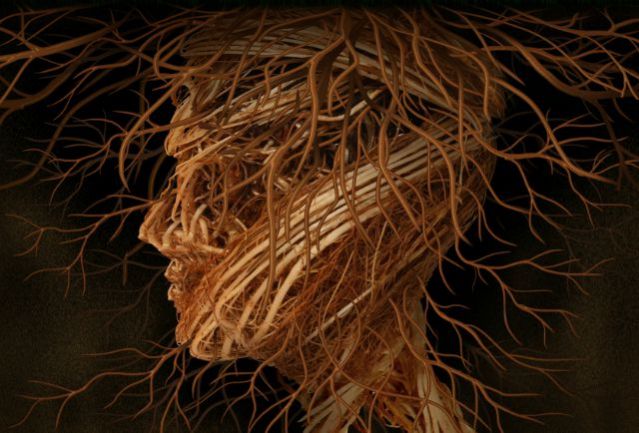

Deep within the brain exists a structure known as the nucleus accumbens. The nucleus accumbens is involved in aversion, motivation, and pleasure. It is responsible for flooding the brain with happy chemicals after a good job, a good meal, or a good lover.

It’s no wonder, then, that when the biochemistry within the nucleus accumbens and its connecting structures break down, people lose control over what makes them feel happy.

They also lose the ability to control themselves.

Controlling dopamine, controlling sex addiction

Sex addiction (while not a clinical diagnosis) is defined as “engaging in persistent and escalating patterns of sexual behavior acted out despite increasing negative consequences to self and others,” according to the Society for the Advancement of Sexual Health (formerly the National Council on Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity).

Although the popular image of a sex addict is a person (usually a man) who coolly throws caution to the wind in search of earthly pleasures, people with sex addiction are usually deeply unhappy with their situation. Like those with alcohol use disorder who feel self-loathing each time they turn to the bottle, sex addicts cannot restrain themselves no matter how much they crave normalcy.

Also like those struggling with alcohol or substance abuse, sex addicts suffer from disrupted activity in their nucleus accumbens and the rest of the brain’s reward circuit. In 2014, researchers found that individuals who were suffering from sex addiction had brains that “lit up” when they viewed pornography, not unlike individuals with substance use disorder.

Scientists suspect that dopamine, a neurotransmitter responsible for motivation and pleasure, is somehow to blame. This is supported by research, which found that drugs that increase dopamine (such as levodopa) also increase activity in the nucleus accumbens when people view subliminal sexual stimuli. In contrast, drugs that reduce dopamine (such as haloperidol) reduce activity in the nucleus accumbens.

Naltrexone can help

Naltrexone is a long-acting opioid antagonist that is most commonly used in the treatment of alcohol addiction. Scientists believe that naltrexone works for alcoholism because it limits the release of dopamine within the nucleus accumbens, thereby reducing the pleasure associated with drinking.

Considerable research has supported naltrexone as a potential treatment for sex addiction as well. Naltrexone has been found to suppress abnormal sexual behavior including frequent masturbation, exhibitionism, compulsive touching of sexual organs, and spontaneous erections. Naltrexone has also been successfully used in paraphilic adolescent sexual offenders.

What about naltrexone makes it so effective at treating both alcohol and sex addiction? Study after study continues to suggest that behind every addiction, behavioral or otherwise, lies a malfunctioning reward center. It makes intuitive sense, then, that a medication that treats one kind of addiction may be able to treat another.

In other words, naltrexone’s powerful effect on dopamine and the reward center seems to be strong enough to treat addiction at its root — the brain.

The future of sex addiction treatment

Is naltrexone the end-all-be-all for sex addiction treatment? Or will another medication come along that can even more effectively shift the disrupted neurobiology within the brain’s nucleus accumbens? Perhaps clinicians will find a way to alter chemistry within the disordered brain without medication — after all, it’s possible for the environment alone to shift genetic expression and neurobiology.

Regardless of the answer, neuroscientists will continue to struggle to understand how the brain ticks in both its normal and addicted state. This invaluable research will open the door to new treatments, new medications, and new hope for individuals in the throes of addiction.

Contributed by Courtney Lopresti, M.S.