Career

What It Really Means To Humanize Work

Mindfulness, values, play, and other themes from the inaugural WorkHuman Summit

Posted June 14, 2015

It was about time. As Derek Irvine, Vice President, Client Strategy and Consulting at Globoforce, pointed out in a quick historical office tour stretching from the Ancient Greeks to the knowledge age, we have “2,000 years of experience in removing humanity from the workplace.” And the window for the human workplace, barely a crack open nowadays, is closing fast: “Someday robots will take over the world. Until then, let’s work human,” Irvine joked.

His company, a leader in employee recognition solutions, took the bull by the horns and hosted the first ever WorkHuman Summit (full disclosure: I was among the speakers) last week in Orlando. More than 400 workplace strategists, HR professionals, designers, journalists, and researchers gathered for a two-day program rich with talks, debate, and workshops, building upon the growing realization that somehow amidst efficiency, productivity, and career advancement, our very humanity has lost out. “We brought our brains and bodies to work, but forgot our hearts,” Irvine said.

Arguably, digital technologies have fostered that disconnect and fomented a stressful culture of extreme connectivity, employee monitoring (and self-monitoring), and relentless efficiency pressures at work. Software is not only “eating the world,” as venture capitalist Marc Andreesen famously said, it is also eating our spirits. Up to 85 percent of workers worldwide are disengaged at work, according to a 2013 Gallup survey. On average, initial enthusiasm on the job fades after six months. The majority of employees report feeling disconnected from their management team and its vision.

There are several things going on here: technology-induced stress, a lack of meaning in the everyday work, and, as a result of that, eroding trust in business leadership. The good news is: a countermovement has been forming over the past few years, and its proposals can be roughly divided into three interrelated areas: work-life integration, workplace experience, and purpose.

Work-life integration: catering to body and soul

In the policy realm, firms have begun to explore flexible schedules, telecommuting, different models of leadership development, family-friendly benefits, and other reforms that help integrate work and life, and adjust traditional structures to a more socially progressive, mobile, and demanding workforce. Like any other function in business, HR has been consumerized, and with the war for talent won by talent, enlightened HR leaders have reframed their function as internal and external “customer service.”

This includes an increasing focus on creating healthy workplaces that promote the individual wellbeing of employees, from changes to the cafeteria food to promoting and rewarding physical exercise, including mental health and happiness. At the individual level, workers are embracing the freedom to indulge in “mindfulness” (including meditation, yoga, and even spiritual exercises at work), spearheaded by leaders such as Arianna Huffington (who joined WorkHuman live via satellite link) or Aetna CEO Mark Bertolini, and inspired by books such as Pico Iyer’s The Art of Stillness or David Gelles’ Mindful Work. Brigid Schulte, author of Overwhelmed: How to Work, Love And Play When No One Has The Time, spoke at WorkHuman about the stress caused by a culture that glorifies constant busy-ness. She suggested we liberate ourselves of the “ideal worker” paradigm, citing email policies that promote “digital detox” and true vacations.

The mindfulness movement is on the rise: at WorkHuman, meditation exercises were part of the main program; the World Economic Forum incorporated numerous sessions on individual wellbeing into its Davos agenda; the Wisdom 2.0 conferences sell out quickly; and Google’s popular “Search Inside Yourself” course has become an institute.

Purpose: inspired by something greater than yourself

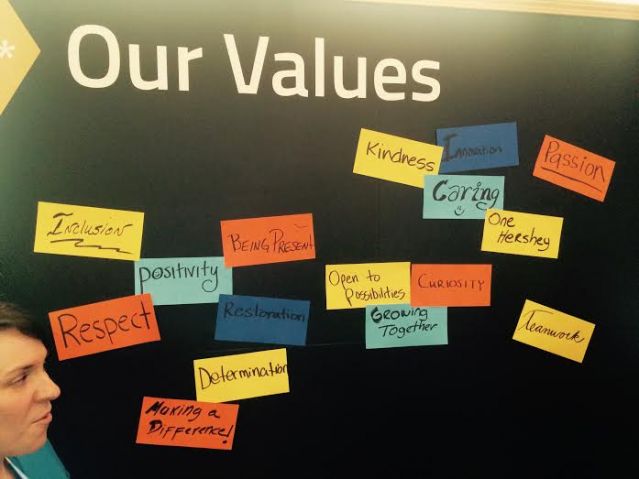

A focus on wellbeing, on a workplace that enables a “good life,” is an expression of a certain set of values. There is of course no such thing as a values-free business (as there is no such thing as values-free decision-making), but the deliberate articulation of values has become more popular lately with companies, in light of social media exposing a company’s actions in broad daylight and evidence that consumers favor companies that are associated with a distinctive social mission.

A clear set of values links employee behavior to the firm’s purpose, the raison d’etre, the why, the overall moral obligation, of the business. At its core is almost always empathy, the ability to feel with and for others. Adam Grant, the author of bestseller Give And Take, who gave a rousing keynote at WorkHuman, translates this into his concept of “productive generosity,” arguing that organizations with a culture of giving (and a low number of “takers”) typically thrive. His research suggests that altruism not only feels good but boosts productivity.

Inevitably, purpose-driven businesses face a heightened risk as the fall from grace can be painful, as Starbucks recently had to experience with its well-intended, but poorly executed “Race Together” campaign. Yet the benefits outweigh the potential reputational damage: purpose-driven companies outperform others in attracting and retaining customer and talent, in particular the meaning-thirsty Millennials. The challenge, however, is to connect a lofty purpose with the day-today work experience, for it will otherwise ring hollow and lead more quickly to cynicism than a culture that doesn’t care much about others to begin with.

Workplace experience: designing for mystery, delight, and play

Workplace culture cuts across all other areas and is a tough one to get right: employers need to straddle a fine line between overwhelming and underwhelming their employees. How much connectivity can they expect without burn-out? On the flipside, at what point does mindfulness hamper your productivity? What degree of routine, comfort, and convenience is right before workers become bored to death and crave more excitement? How public should the office culture be, or how private? How open, how closed? Is transparency always positive?

The workplace is where the action is, and it must indeed be an arena of action. Key elements of employee engagement are play, surprise, and even mystery. It was no coincidence that one of the WorkHuman workshop sessions was focused on Improv theatre. Brigid Schulte emphasized in her talk that play gives us access to a broader version of ourselves and allows us to try on alternative identities that bring in our more emotional selves, fostering creativity, innovation, and trust. She referred to neuro-scientific findings that show how the brain literally expands through play.

Tania Luna, co-founder of Life Labs, author of the book Surprise, and self-appointed “surprisologist,” heralded the value of “playfulness” and presented surprise as its key ingredient. Surprises make us come alive, she said, they are the source of the “wow” moments that companies like JetBlue now quantify. Surprises create memorable experiences that shake up our routines and let us fight boredom and view the world through fresh eyes every day. Luna has helped companies such as Etsy and Google create surprises and is now running “The Experiment,” in which participants agree to being surprised at some point over the next few years.

Mystery, too, plays with the unknown, and companies have begun to make it a part of the workplace experience: from secret rooms (the latest office design trend at Bay Area tech firms) to secret societies (e.g. Etsy’s "Ministry of Unusual Business") to the start-up Prime Produce, which holds events in the dark. As Virtual Reality technology is becoming mainstream, it will soon broaden the playing field and further contribute to the gamification of the workplace.

Happiness is overrated

Surprise and mystery are disruptive by design, and they celebrate the importance of “small moments of wonder” that make up our work life between top and bottom line, as opposed to a more coherent narrative (purpose) or state of wellbeing (happiness). Moments are about joy rather than happiness, which is, as positive psychologist and leading gratitude researcher Robert A. Emmons told me at WorkHuman, “not even an emotion.” A happy workplace is not necessarily a more emotional workplace (and vice versa). A truly humane workplace embraces not the perfect equilibrium but the extreme peeks of our emotional landscape, the full range of human expression. It creates space for grief and sadness as much as for joy.

In the end, it is the intensity of experience that gives us meaning, the degree to which we can be our most vulnerable, our most emotional, our most human selves at work. This matters because not only do we spend the majority of our waking hours at work; most of us also view work relationships as critical for the quality of their life.

The ROI of meaning? Meaning!

The WorkHuman Summit offered an excellent snapshot of the paradigm shift that is underway, and it presented many of the emerging new concepts for a more humane workplace. All these concepts are advancing the conversation and have strong potential to humanize the enterprise. But they are also still fundamentally flawed because they are ultimately instrumentalist: they are reduced to being “success factors,” performance enablers that promise more productivity, more career advancement, more success. We accept failure only as stepping stone to ultimate victory, not as an inherently rich, character-forming human experience. We encourage altruism to boost productivity. We monitor happiness to win the talent war. We cater to the heart to maintain our bleeding edge. We add some surprise so there is none in the bottom line. We maximize and (self-)optimize to succeed.

It is laudable that we have begun to measure what really matters, that we have started to implement metrics for wellbeing, happiness, and purpose. But we will only be truly human at work if we value and manage what we cannot measure, if we create spaces and experiences for our elusive, unquantified, erratic, inconsistent, unpredictable selves. The ROI of meaning is not more money. It is meaning.

HR and marketing can be the great humanizers

HR and marketing must join forces for this mission. They are the emotional stewards, the strongholds of the heart, in any organization, and at the same time they are also the ones most threatened by datafication, quantification, and algorithmic decision-making. Empowering HR and marketing to be real strategic drivers in maintaining human agency, in building a culture of wellbeing, learning, and meaning, is the first step to empowering humans at work.

Humans may survive robots at the workplace, but we will only thrive if we keep investing in what makes us inherently human: vulnerability, empathy, intuition, emotion, and imagination. We are human because we suffer, because we can feel—and feel for others. We are human because we can dream.

To learn more, please see my book The Business Romantic: Give Everything, Quantify Nothing, and Create Something Greater Than Yourself (HarperCollins).