Eating Disorders

Rumination Syndrome: A Lesser-Known Eating Disorder

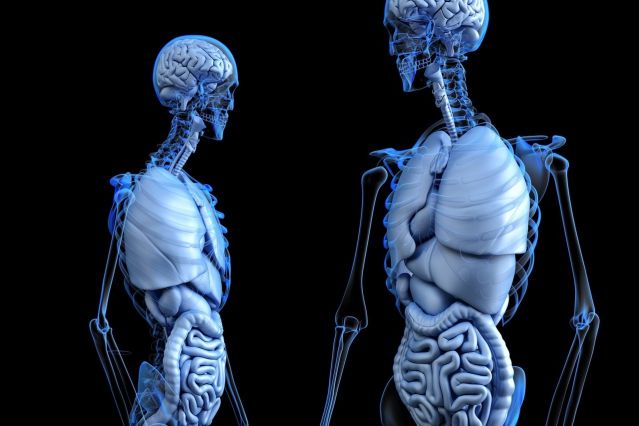

Miscommunication between the gut and brain can affect eating behavior.

Posted October 8, 2023 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Rumination syndrome is a disorder involving regurgitation of undigested food.

- Rumination syndrome is classified as both an eating disorder and a disorder of gut-brain interaction.

- Miscommunication between the gut and brain could be one cause of rumination syndrome.

You probably don't think about what happens to the food you eat after you swallow it. You're assured that the food will travel through your body as planned, providing you with the nutrients you need to thrive and survive. The body, however, has an intricate system of tube-like organs with precise muscle movements that allow food to travel throughout the body in one direction.

The Digestive System

After food is swallowed, it enters a long tube called the esophagus. The esophagus is the tunnel that takes food from the mouth to the stomach for digestion. For food to enter the esophagus, it must get past the upper esophageal sphincter (UES),1 a group of muscles that prevent air from entering the esophagus. Swallowing relaxes the muscles that keep the UES closed, allowing food to pass into the esophagus.

Food is pushed down the esophagus by muscle contractions called peristalsis, which take the food to the lower esophageal sphincter (LES).2 The LES is a group of muscles that keep food in the stomach and protect the esophagus from stomach acid. When food reaches the lower part of the esophagus, the LES relaxes, allowing food to exit the esophagus and enter the stomach for digestion.

Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction

With as much as we know about the digestive system, some of it remains a mystery. Disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBIs) are such an example. DGBIs are syndromes that involve disturbances in gut functions (e.g., mucosal, microbiota, pain sensitivity, and muscle contractions), the immune system, and how the brain interprets and processes gut signals.3

A commonality across DGBIs is that there are no structural or chemical abnormalities attributed to them. The ambiguity of what causes these gut disorders makes them best explained by disruptions in how the gut and brain communicate.

Gut-Brain Communication

The gut and brain are always communicating via nerves and chemicals to regulate bodily systems (e.g., digestive and immune), behavior (e.g., eating), emotions, and mood.4 Disconnects between gut-brain communication can, therefore, lead to poor functioning in a number of bodily and psychological processes, including food movement throughout the body.

Rumination Syndrome

Rumination syndrome (RS) is a DGBI that is also classified as an eating disorder.5 Individuals with RS report involuntary and consistent regurgitation of undigested food, typically within one to two hours after eating. Adults with RS are more likely to spit the regurgitated food out compared with infants and youth, who are more likely to rechew and swallow it.

Medical professionals have determined that the abdominal muscles of people with RS start to contract after food enters the stomach, putting pressure on the stomach.6 This pressure relaxes the LES, allowing food to reenter the esophagus and eventually the mouth. Because these stomach contractions happen soon after food enters the stomach, the food isn't in there long enough to be digested.

There is speculation that the muscle contractions observed in RS are a learned, unconscious behavior, perhaps in response to significant stress or stomach discomfort after eating. In this way, individuals with RS might "retrain" their digestive processes to avoid discomfort.

Diagnosing Rumination Syndrome

The lack of explanations for RS makes it difficult for medical professionals to diagnose this syndrome.5 Typically, physicians rely on patient interviews to diagnose RS using Rome IV or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) 5 criteria. For a person to be diagnosed with RS, they must experience regurgitation of recently eaten food for several consecutive weeks, with no signs of retching or nausea during regurgitation.

Unfortunately, RS is often misdiagnosed as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), a disorder where digested food reenters the esophagus from the stomach.7,8 The difference between GERD and RS is that, in GERD, stomach acid flows up the esophagus with food. The food in RS is undigested and, therefore, not acidic. Making these distinctions between RS and GERD is important for accurate diagnoses and treatments.

A more objective way to diagnose RS than patient interviews is esophageal manometry.8 Esophageal manometry is a test that measures pressure in the esophagus as food moves through it. Kessing et al. (2014) found that individuals with RS have increased pressure in the esophagus and abdomen after eating compared with people who have GERD. Finding more objective ways to diagnose RS could improve the accuracy of RS prevalence estimates, which are currently just 3%.9

Rumination Syndrome Treatment

The standard, most effective way of treating RS has been diaphragmatic breathing (DB).6 DB is a breathing technique where individuals breathe slowly and deeply through the nose into the diaphragm without moving the chest. The health benefits of DB are numerous, with positive impacts on the GI tract, respiratory and cardiovascular systems, and the brain.

DB can be done with or without electromyography (EMG)-guided biofeedback, a device that records muscle activity.10 EMG is beneficial in RS treatment because it gives people with RS a visual of what happens in their abdominal area after they eat. By using EMG in RS treatment, people with RS can practice reducing abdominal muscle activity and increasing diaphragm activity.

If DB is ineffective or if an individual with RS has difficulties with DB, physicians will likely seek other behavioral interventions.5 If alternative behavioral interventions do not improve RS, patients might be prescribed Baclofen, a muscle relaxant, to treat RS.

Conclusions

RS has the potential to disrupt a person's quality of life. People with RS might avoid social situations that involve eating because they fear the social repercussions of their behavior. Consistent food regurgitation might also damage the esophagus or lead to malnutrition. Health professionals, therefore, need to be educated on how to diagnose and treat this disorder.

To find a therapist, please visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

1.) Sivarao, D.V., & Goyal, R.K. (2000). Functional anatomy and physiology of the upper esophageal sphincter. Am J Med., 108. 27S-37S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00337-x.

2.) Hershcovici, T., Mashimo, H., & Fass, R. (2011). The lower esophageal sphincter. Neurogastroenterol Motil., 23, 819-830. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01738.x.

3.) Drossman, D.A., & Hasler, W.L. (2016). Rome IV - Functional GI disorders: Disorders of gut-brain interaction. Gastroenterology, 150, 1257-1261. doi: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.03.035.

4.) Carabotti, M., Scirocco, A., Maselli, M.A., & Severi, C. (2015). The gut-brain axis: Interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Annals of Gastroenterology, 28, 203-209.

5.) Murray, H.B., Juarascio, A.S., Di Lorenzo, C., Drossman, D.A., & Thomas, J.J. (2019). Diagnosis and treatment of rumination syndrome: A critical review. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 114, 562-578. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000060.

6.) Sasegbon, A., Hasan, S.S., Disney, B.R., & Vasant, D.H. (2022). Rumination syndrome: Pathophysiology, diagnosis and practical management. Frontline Gastroenterology, 13, 440-446. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2021-101856.

7.) Nakagawa, K., Sawada, A., Hoshimasa, H., et al. (2019). Persistent postprandial regurgitation vs rumination in patients with refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: Identification of a distinct ruminiation pattern using ambulatory impedance-pH monitoring. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 114, 1248-1255. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000295.

8.) Kessing, B.F., Bredenoord, A.J., && Smout, A.J. (2014). Objective manometric criteria for the rumination syndrome. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 109, 52-59. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.428.

9.) Josefsson, A., Hreinsson, J.P., Simrén, M., et al. Global prevalence and impact of rumination syndrome. Gastroenterology, 162, 731-742. doi: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2021.11.008.

10.) Barba, E., Accarino, A., Soldevilla, A., et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of biofeedback for the treatment of rumination. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 111, 1007-1013. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.197.