Anxiety

Arrested for Skipping Church

Personal Perspective: It taught me how much I was loved by my father.

Posted November 11, 2022 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Dad gave me 15 cents to buy a soft drink and a candy bar before the Sunday night church service. The evening began with Youth Group, followed by dinner in the church social hall, then a 20-minute break before services. At the candy and soda vending machines, I ran into my friend Hal and a new kid named Carl, whom I’d just met at Youth Group (I have changed their names to protect their privacy).

As Hal and I reviewed our choices, Carl offered a suggestion, “Y’all save your money. I have Coke and cookies at my house, and I live just a few blocks from here.”

I agreed to do something I knew was wrong.

It meant skipping church, but at 13 years of age, neither Hal nor I really wanted to sit through a boring sermon, so we agreed to go.

The three of us talked busily all the way to Carl’s house, discussing important teenage topics such as our favorite bands, cars, and TV shows. Meanwhile, I didn’t watch how we got there as we traversed the city streets of uptown Atlanta. At Carl’s, we consumed the treats he promised while watching a 30-minute sitcom on TV; then it was time to go back to the church, meet up with our parents, and go home.

It had gotten dark, and I did not know how to get back to the church, but I wasn’t worried because Carl was leading us. Then, a block from his house, Carl stopped in front of a closed liquor store and asked, “Hey, y’all wanna get some free money?”

“Sure!” Hal and I replied.

Carl then pulled two screwdrivers from his back pocket and started trying to pry open the coin-slot box on a newspaper vending machine. Hal joined in as I watched uncomfortably. This was not something I wanted to be involved with, so I said, “Guys, can we just go back to the church?”

This was not what I agreed to do.

Carl replied, “This will just take a minute; I’ve seen my friends do this many times.”

As the seconds ticked past, I felt more and more uncomfortable. I wanted to leave, but as I looked around, I had no idea which way to go. We had walked at least six city blocks, including several turns, in order to get to Carl’s house, and I had not paid any attention. I had foolishly put myself into an untenable position, and I was angry at myself for being so stupid. But, more than anything, I was feeling extremely vulnerable and nervous.

I couldn’t stand it any longer—even though I didn’t know where to go—I had to get away from there. I spotted a narrow street or alley that ran between the liquor store and an office building next to it—it seemed to go in the general direction that we’d been heading—so I started walking toward it and said, “Guys, I’ll wait for you at the other end of this street.”

“Okay, we’ll be with you in a minute.” Carl replied and then added with a chuckle, “You can be our lookout.” I grimaced at the latter because it implied that I was participating, which I was not, but as a 13-year-old, I didn’t have the confidence or self-esteem to insist he stop and show me back to the church.

I quickly walked to the end of the street and waited. And waited. I had hoped to spot the church steeple, but between the hills and the tall buildings, it was nowhere in sight. Minutes passed while my anxiety level increased. I kept watching the little road for them to walk my way, but it remained empty. More than 10 minutes later and still no one appeared. Suddenly I saw automobile headlight beams illuminating the outer wall of the office building as if a car had parked at an angle in front of the liquor store. I yelled down the alleyway, “Hal, Carl, where are you?”

Surprise!

I heard no response, so I walked toward the headlights. When I turned the corner, I saw it was a police car. A policeman grabbed my arm and said, “You’re under arrest!”

He didn’t handcuff me but opened the back door of his car and pushed me in, where I joined Carl but not Hal. Carl told me that Hal ran away when he saw the police car. I immediately started crying. I cried harder than I ever have in my life. I was terrified. Exactly what I wanted to avoid had happened.

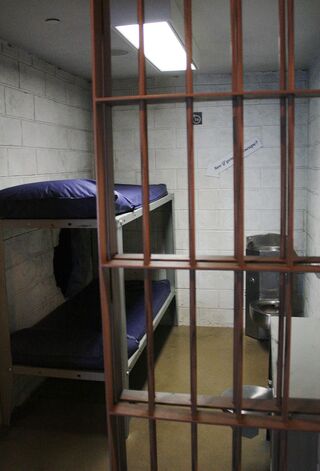

The policeman took us to a juvenile facility where we were told to phone our parents. We were not photographed, fingerprinted, or put in a jail cell, but one was right there where we could see it, and it looked plenty intimidating.

While we waited for our parents, I was shocked and surprised to see Hal and his parents show up. When Hal got back to the church, he told his parents what happened, and they turned him in to the police. My parents and Carl’s mother eventually arrived, and we were released into their custody. All three of us were given a date to meet with a probation officer.

Walk of shame and consequences

I was relieved to get home with my parents but ashamed to explain to them how I got into trouble. Mother screamed at me, but Dad was solemn and stern. He interrogated me until he understood all the details of my ignominious adventure. When he was finished, he stated that my punishment would be a home restriction, after school and on weekends, for the next six weeks. He also forbade me from telling any of my friends or acquaintances, at school or church, about the incident. He explained that was to preserve my reputation.

A few weeks later, our date with the probation officer arrived; I showed up with Dad, Carl with his mother, and Hal with both of his parents. The probation officer told us the charge was larceny and that we could sign a form admitting our guilt, write a 200-word essay on why we should not have committed the crime, serve two years probation, and then if we stayed out of trouble, the charges would be expunged from our record when we turned 18 years old. Alternatively, if we plead not guilty, we would be sent to Juvenile Court for a trial, and if found guilty there, we could be sentenced to jail time.

Hal and Carl chose to sign the form and write the essay. My dad looked at me and asked, “Did you tell me the truth?”

Dad made the call.

I replied, “Yes.” And he declared, “You don’t plead guilty to something you didn’t do.” He then turned to the probation officer and said, “We’ll go to trial.” Those words terrified me; I would’ve been content to just sign the form and write the essay, but at the same time, I was happy that Dad wanted me to stand up for the truth.

Dad hired my Uncle Gene, who was an attorney, to represent me in court. I told my story to him, and he subpoenaed Hal and Carl to be my witnesses. Three months later, on the day of the trial, the police officer, who was the only witness against me, did not show up. My uncle made a motion to the court that if the prosecution did not have a witness, then the charges should be dismissed. The judge agreed, and just like that, I was free to go. Hal and Carl cheered my victory, with Carl exclaiming, “Wow, your uncle is better than Perry Mason!” All in all, it was a rather unspectacular ending compared to the months of anxiety I’d experienced.

I learned the importance of fatherhood.

Initially, I was just happy that it was all over, but in time, the experience yielded several important life lessons. The obvious ones were don’t neglect the truth or situational awareness, but it was what I learned about my dad that has stuck with me the most. It was during those early teenage years that I was most at odds with him, but I learned that he loved me anyway and wanted to protect me as well as teach me how to protect myself. I would lose him six years later when the Swine Flu vaccine of 1976 triggered a blood clot in his brain, but for the 19 years that I had him, he laid the foundation for my moral compass and the parent I would later become.