Evolutionary Psychology

How to Really "Get" Evolutionary Psychology

Evolutionary Constructionism: Really "Getting" Evolutionary Psychology

Updated June 17, 2024

If a tree falls in a forest, and there is no one around, does it make a sound?

Most folks think that the answer to this question is open and debatable. It isn't. There is a right answer and a wrong answer.

What do you think, yes or no?

Many people are inclined to say "yes" because they think that sounds exist out there in the real world, and, via our ears, we simply bring them inside of our heads.

However, let me suggest that this is very incorrect.

If by "sound" you mean the subjective experience of the crackling of the wood and the deep thump of the tree hitting the ground, the correct answer is: No -- there is no sound if no one is there.

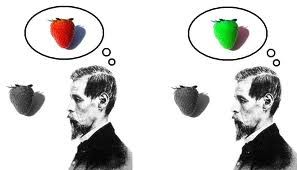

Let me go further. Outside of our heads there is nothing of the perceptions that constitute our subjective reality. No sounds. No colors. No tastes or smells. No hot and cold. This is a difficult and strange concept for some to grasp. Once the idea really sinks in, it can even be a bit disconcerting.

Why? Because we are bathed in a world of our perceptions, and that is our reality. We experience a world that gives us the illusion that perceptual qualities exist "out there," and that our senses are just bringing them to us "in here." But our perceptions do not exist "out there." Instead, we construct perceptions inside of our brains.

Sure, there is energy (e.g., pressure waves in the air we associate with sound, a frequency of electromagnetic energy we associate with the color red, etc.) but energy itself is bereft of any perceptual content. The wavelength of light that we associate with red has no "redness" in it.

Stunningly, both Galileo and Newton somehow managed to intuit this.

"...if ears, tongues, and noses were removed, I am of the opinion that there would be an end of smells, tastes, and sounds.... I take (these perceptions) to be mere (constructions)... (they) reside only in the consciousness. Hence if the living creature were removed, all these qualities would be wiped away and annihilated."

-- Galileo, The Assayer, 1623. Quoted in Crowther, Six Great Scientists (1995, p. 77)

"The rays (of light), properly speaking, are not themselves colored."

-- Isaac Newton, 1704

And, a similar quote from a more modern source:

"If real is what you can feel, smell, taste and see, then 'real' is simply electrical signals interpreted by your brain."

-- Morpheus, The Matrix (film)

That is, we live in a perceptual "virtual reality" of our own creation.

How the brain manages to construct the content of our perceptions, or "qualia," is still unknown. But, from a scientific perspective, it is presumed that perceptions are created as a function of the operation of the brain.

Now, what does this have to do with evolutionary psychology?

If we accept that perceptions are generated by the brain, and that the brain evolved over countless generations, then we arrive at the conclusion that perceptions are constructed by evolved psychological adaptations. We might call this way of thinking "evolutionary constructionism."

Evolutionary constructionism suggests that our entire perceptual world relies on the operation of evolved mental mechanisms. In fact, not just our perceptual world, but our basic human emotions, motivations and cognitions (which are also "evolutionary constructions"). When viewed like this, one can really start to "get" evolutionary psychology. And, its significance starts to sink in: evolutionary psychology is a foundational way of thinking in order to understand human nature and behavior.

Evolutionary constructionism can be contrasted with social constructionism, its primary theoretical rival.

Social constructionism claims that we bring things "out there" inside. It suggests that our minds start out as "blank slates" to be written on by the outside world. It has no theory about how perceptions are created, or, even why we have them in the first place (unless they too are somehow "socially constructed"). Many social constructionists believe in evolution, but only in terms of the body, or "below the neck" evolution. Above the neck (the brain), they are similar to creationists -- the brain "just is" and needs no explanation of why it evolved to be as it is. They are what might be termed "psychological creationists."

"Evolutionary constructionism" suggests the opposite. All of our perceptions (e.g., the color red) are not brought in from "out there." Instead, they are "constructed" by evolved brain mechanisms because those perceptions helped our ancestors to survive and reproduce. Evolutionary psychologists are, of course, psychological (not just physical) evolutionists. Minds do not start out blank, but are a collection of evolved psychological adaptations that serve particular functions.

Of course, seeing our perceptions for what the are, "illusions" of what is "out there," is very difficult. We literally live them, and we operate everyday under the assumption that we see and hear things that are "out there." Intuitively understanding our evolved psychological nature isn't easy because we "swim" in it everyday. In the same way, a fish doesn't intuitively understand water since it swims in it everyday. It just "is."

With respect to sex differences, males and females are two different "morphs" within a species, and have different life histories and reproductive strategies. Accurately understanding the opposite sex should not be easy either, since we "swim" in our basic "male nature" or "female nature." Males assume that females perceive the world as they do, and vice versa. However, when it comes to sexually dimorphic psychological adaptations, those perceptions are likely to be inaccurate. Suppose one sex was colorblind. They would assume the other sex saw the world the same way. And, if fact, there are more colorblind men than women, and, overall, women have a better sense of hearing than do men.

Once you understand that our perceptual world is constructed inside of our brains, and that brains evolved, one starts to really "get" evolutionary psychology. There are potentially infinite ways to perceive, feel, think and desire. Human nature is but one subset of a vast set of possibilities that have been pruned by natural and sexual selection. We suffer from "instinct blindness." To us, our human nature is mostly invisible. However, evolutionary psychology can help us to scientifically illuminate our human nature that we can't see because we are swimming in it.

...every organism only perceives what it needs

For survival and reproduction,

like ultraviolet for bees

And sonar for bats,

there’s so much we can’t see.

But you still can’t see me

Call me "human nature."

Without using evolution as an illuminator,

You can't see me.

-- Baba Brinkman, You Can't See Me (rap song)

http://bababrinkman.bandcamp.com/track/you-cant-see-me

Also see:

Evolutionary Enquiry into the Structure of Perception, by Taylor Coplen

BBC program "Is Seeing Believing?"

http://v.youku.com/v_show/id_XMjIwMTcyMzc2.html

Dennis McKenna - We're on Drugs All The Time

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kSuWsN28_ag