Sleep

A Writer in Pain

As an unwelcome, cruel guest, pain infiltrates the body.

Posted July 3, 2022 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- There are often no words to describe chronic, unbearable pain.

- As incomprehensible to others, pain is the quintessential private experience.

- Creative people endure their pain through art.

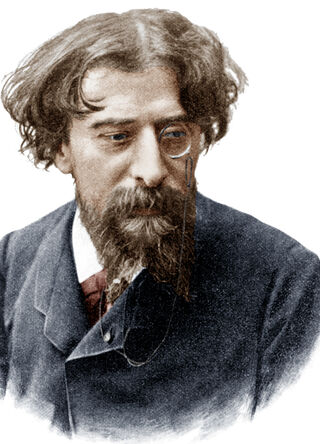

“Every evening, a hideously painful spasm in the ribs … Armour is exactly what it feels like, a hoop of steel cruelly crushing my lower back. Hot coals, stabs of pain, sharp as needles,” wrote the 19th-century French novelist Alphonse Daudet. “Pain finds its way everywhere, into my vision, my feelings, my sense of judgment; it’s an infiltration,” he added (Daudet, La Doulou, 1930; 2018).

Daudet is little known as the novelist, playwright, poet, and journalist he was outside of academia today—“a substantially forgotten writer” (Barnes, 2018). He was, though, quite well-known during his day by authors like Henry James, who translated one of his novels, and Charles Dickens (Barnes). Marcel Proust had been a young protégé of Daudet (Dieguez and Bogousslavsky, 2005), and Daudet was considered among the great literary figures, including Baudelaire, Flaubert, and de Maupassant, who suffered from syphilis (Barnes).

Tertiary syphilis, tabes dorsalis, i.e., neurosyphilis, was a “wasting disease” (Barnes) for which there was no effective treatment at the time. It usually appeared from 15 to 30 years after initial infection and resulted in demyelination of the posterior columns of the spinal cord and posterior roots of spinal nerves. Patients developed progressive motor ataxia, with uncoordinated movements, sensory abnormalities, and severe pain, among its many symptoms (Tatu and Bogousslavsky, 2021).

Wrote Daudet, “My poor carcass is hollowed out … there are long days when the only part of me that’s alive is my pain.” “Sometimes I feel as if I don’t own part of myself—the lower half. My legs get confused.”

Daudet had considerable generalized muscular atrophy and presented as a “shrunken old man” by his mid-40s (BMJ, 1932). Daudet’s mental capacity, though, was not affected, except when he was on morphine, to which he became addicted. His handwriting deteriorated but his vision, though significantly disturbed, was mostly preserved.

Daudet would live 12 more excruciating years after the insensitive Jean-Martin Charcot, “the greatest neurologist of the day,” and teacher/colleague of Sigmund Freud (Camargo et al, 2018) bluntly declared Daudet “incurable, lost” when he was age 45 (Barnes).

Despite his symptoms of unbearable constant nerve pain and progressive incoordination, Daudet continued his writing, with ten subsequent publications and plays (de Montalk, 2019).

Among his extensive writings, Daudet began a journal, “notes,” La Doulou, documenting his experience. He wrote, “Are words actually any use to describe what pain really feels like?" Words come later, "when things have calmed down. They refer only to memory, and are either powerless or untruthful," he added.

“Pain is the black hole into which language seems to disappear” (Frank, 2011). “Pain—has an Element of Blank” in which “It cannot recollect/When it began—or if there were/ A time when it was not…” (Emily Dickinson, Collected Poems, Life XIX).

As the "quintessential private experience, pain severs our engagement with the world..our isolation is exacerbated by the incomprehension of others" (Biro, 2011). Fortunately, Daudet persevered and converted his private experience into a public testament to his suffering.

La Doulou, translated in recent years by author Julian Barnes, In the Land of Pain, had first been published by Daudet’s wife Julia Allard in 1930, well after her husband’s death, at age 57, in 1897.

His wife, herself a writer, and “his intellectual and creative companion” (de Montalk) and whose portrait was painted by Renoir (Dieguez and Bogousslavsky), “saved him from a dreadful life of careless debauchery” (Barnes). While his syphilis lay dormant, Daudet and Julia would have two sons, and a daughter who was conceived during one of his stays at a therapeutic spa.

Before the discovery of penicillin in the late 1920s which treated the early stages of syphilis and virtually eliminated tertiary syphilis, there were truly gruesome therapies, including the use of arsenic, poignantly described in the film Out of Africa, based on the memoir by Isak Dinesen.

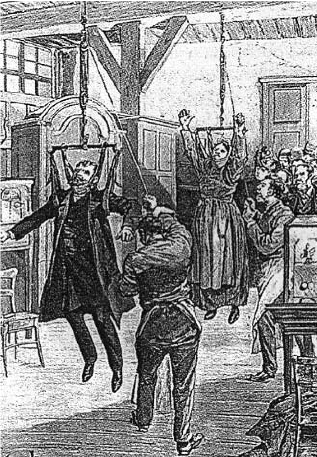

Of the many treatments to which Daudet was subjected, though, Charcot would recommend the cruel Seyre traction technique. Originally from Russia (Dieguez and Bogousslavsky), this procedure involved suspending a patient, sometimes only by his jaw or elbows, for several minutes in the hope of alleviating movement difficulties that were typical of tertiary syphilis. The so-called "treatment" would cause the patient “excruciating pain” without any benefit (Barnes); Daudet underwent 13 of these suspensions (Dieguez and Bogousslavsky; Daudet).

Daudet, who called himself a “wounded Don Juan … Don Juan as amputee,” was hardly a faithful husband, but he tried to shield Julia from the incessant pain he suffered. When Julia would enter the room, he would rise, and his voice would be filled with optimism, only barely able to speak from the pain just before and collapsing back into his chair once she left (Barnes). “Our pain is always new to us, but becomes quite familiar to those around us. It soon wears out its welcome, even for those who love us the most … Everyone will get used to it except me. Compassion loses its edge,” he wrote.

“Suffering is nothing. It’s all a matter of preventing those you love from suffering … I don’t want to read weariness and boredom in the eyes of those dearest to me,” Daudet continued. Lynn Greenberg offers a similar sentiment, “I could only offer the broken-record response, ‘What’s more is there to say? I feel exactly the same as yesterday” (The Body Broken: A Memoir, 2009).

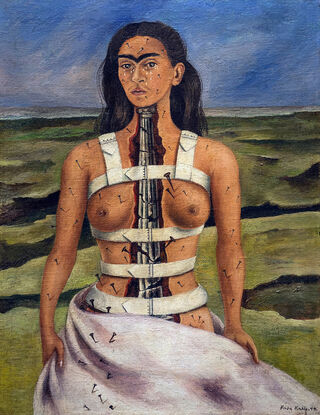

“Illness narratives … are acts of witness, telling truths that are too often silenced because they speak” of what we all would rather ignore (Frank). Artists, as well as writers, can create their own "illness narratives," as evidenced visually, for example, in the paintings of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo (1907-1954). Kahlo contracted polio at age 6 and subsequently was a victim of a devastating trolley car accident that led to a life of chronic debilitating pain, multiple spine surgeries, and ultimately a leg amputation (Courtney et al, 2017). She used an image of a skeleton and various metal contraptions in The Sleep, as well as nails, knives, swords, and arrows—weapons—in her other paintings, such as "The Broken Column," as metaphors for her pain (Biro).

“Nothing but terror and despair at first; then, gradually, the mind, like the body, adjusts to this appalling condition," wrote Daudet. The power of creativity, whether in writing or art, enables the mind to endure.

References

Biro D. Listening to Pain: Finding Words, Compassion, and Relief. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. 2011.

Alphonse Daudet’s Illness (no author cited). The British Medical Journal 2 (3745): 722 (October 15, 1932).

Camargo CHF et al. Jean-Martin Charcot’s influence on career of Sigmund Freud, and the influence of this meeting for the Brazilian Medicine. Revista Brasileira de Neurologia 54(2): 40-46, 2018.

Courtney CA; O’Hearn MA; Franck CC. Frida Kahlo: portrait of chronic pain. Physical Therapy 97(1): 90-96, 2017.

Daudet A. In the Land of Pain. Edited and translated by Julian Barnes. London: Vintage, 2018.

De Montalk S. “The Vendor of Happiness: An interview with French novelist Alphonse Daudet (1840-1897). In: Communicating Pain: Exploring Suffering Through Language, Literature and Creative Writing. New York: Routledge: Taylor and Francis Group, 2019, pp. 114-130. https://read.amazon.com/?asin=B07JKHK1MT&ref_=dbs_t_r_kcr (Retrieved 7/2/2022).

Dickinson, E. The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson. “The Mystery of Pain,” or “Pain—has an Element of Blank,” in Life, Poem XIX, 1896. Start Publishing LLC, 2012: https://read.amazon.com/?asin=B00AWJMV9W&ref_=dbs_t_r_kcr (retrieved 7/2/2022).

Dieguez S; Bogousslavsky J. “The One-Man Band of Pain: Alphonse Daudet and His Painful Experience of Tabes dorsalis. In: Neurological Disorders in Famous Artists (Frontiers of Neurology and Neuroscience, Vol. 19), edited by J. Bogousslavsky and F. Boller. New York: Karger, 2005, pp. 17-45.

Frank AW. Metaphors of Pain. Literature and Medicine 29(1) (Spring 2011): 182-196; 225.

Greenberg L. The Body Broken: A Memoir. New York: Random House, 2009.

Tatu L; Bogousslavsky. Tabes dorsalis in the 19th century. The golden age of progressive locomotor ataxia. Revue Neurologique 177: 376-384, 2021.