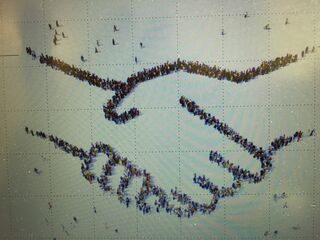

Trust

Gauging Trust as the Pandemic Continues

Has trust been further frayed, or has lock-down made Americans more empathetic?

Posted June 28, 2020 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Three years ago, researchers working with the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), conducted representative surveys in the U.S. and other countries to test a new methodology and gauge people’s levels of trust in each other and in their governments. As described in a post here on Trust in Government, the survey asked participants to play a set of economic decision games with other anonymous participants, to complete a set of implicit association tasks aimed at assessing trust in government, and to answer a set of survey questions on a variety of topics including trust in various categories of people and in various government bodies and branches (including the judicial system and the police).

In mid-April of 2020, following the first month of stay-at-home efforts by many Americans, members of the research group began to prepare a second round of the survey, including questions about individuals’ and their families’ experiences with Covid-19. When the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis policemen burst into the headlines and triggered a wave of demonstrations during the last stages of survey preparation, a question about views on that issue was also added. The survey of slightly over 1000 American adults from every region, age group, and income category, is being completed as of this writing. The group’s analysis of inter-ethnic dynamics based on the 2017 survey was also completed and submitted for potential publication in a scientific journal at about a week earlier.

In its experimental game portion, the TrustLab survey asks participants to decide how much of $10, if any, they want to send to a second, anonymous participant, knowing that that participant has already been given $10 by the researchers and will receive three times the amount sent. The receiver of the money can then return money to the sender, money that this time will neither gain nor lose value.

Although the two parties could end up sharing a doubled sum, the first decision-maker should hold onto every dollar unless she’s either altruistic or willing to trust the second to return at least as much as was sent, something the latter may conceivably do out of a sense of obligation or fairness. Experimental economists and some psychologists have used this task, often called the “trust game” and referenced multiple times here, as a concrete indicator of how much people in a given society trust each other.

In the 2017 and in the current U.S. TrustLab survey, the game is played not only with a generic counterpart, but also with counterparts identified to the first decision-maker as belonging to a specific ethnic or racial category—concretely: Hispanic or Latino, non-Hispanic White, and African American.

Because participants provide their own ethnic and racial self-identification after completing all games and survey questions, this makes it possible to observe whether participants who identify themselves as belonging to one of these three categories or to a fourth one (say Asian, Native American, or more than one category) appear to trust those in their own group more than they trust others.

On average, the results from the first survey support that this is so, but differences tend to be small, and interestingly, the differences in trust between the identified groups in the U.S. were substantially smaller than those for German subjects of “rooted German” origin dealing with residents of Turkish or East European background.

What impact on behaviors and responses in the new wave of the survey may result from Covid-19 and from heightened attention to biased treatment of African Americans, is difficult to predict with any certainty. I had a window into some of what we might see when an unrelated decision experiment being conducted in the U.S. this past March and April began to show qualitative changes in behaviors after the reporting of the first documented U.S. death from Covid-19.

That survey was temporarily halted, then resumed adding only the question “Are you feeling stressed or concerned about the novel corona virus (COVID-19)?” with possible answers 1 = “No, not at all concerned,” 2 = “No, not concerned,” 3 = “Neither concerned nor unconcerned,” 4 = “Yes, somewhat concerned,” and 5 = “Yes, very concerned.”

Out of 2200 survey-takers of diverse ages and education living in all parts of the United States, 45% chose answer 4, 34% answer 5, and 4%, 7% and 10%, respectively, gave answers 1, 2 and 3. A preliminary analysis suggests that age, gender and political orientation are among the most important determinants of participants’ responses, with the average answer rising by 0.13 on the five point scale for individuals above age 40, falling by 0.17 for males, and rising by 0.28 if the respondent’s self-assessed political orientation is more liberal than the median respondent. The response also rises in a statistically significant way with each additional day that the respondent’s state has had a stay-at-home order or advisory in effect.

Interested readers can try out a truncated and slightly modified version of the TrustLab survey, minus its incentivized games, by clicking here. While not a scientific research survey, it will be interesting to see how answers compare to those given by the official research participants.