Autism

Why Many People With Autism Dislike Functioning Labels

Calling people with autism high- or low-functioning can be invalidating.

Posted August 23, 2022 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Being called high-functioning can invalidate the daily struggles of people with autism.

- Being called low-functioning can be hurtful and stigmatizing to those with autism who need more help with their disability.

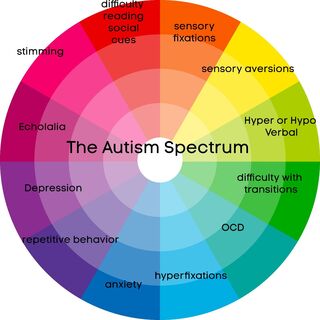

- The autism spectrum isn't a linear spectrum between very autistic and a little autistic but rather a wheel with many colors and shades.

If you are an autistic person who can hold a job and pay bills, you will hear two things. You hear “you don’t seem autistic” and “you must be high-functioning."

I think a lot of people mean to say these things with great kindness. They are trying to tell us that we seem normal, which to them is often the highest compliment they can give. After all, who doesn’t want to be normal?

The problem is that if you feel completely abnormal, the compliment is lost on you and can be heartbreaking and invalidating. Even if you can complete daily living tasks and succeed in some areas of life, if you have autism, beneath that, you feel profoundly other. Life is a struggle.

Masking and the myth of being "high-functioning"

Those of us that are perceived as high-functioning are just very good at masking. Masking is a skill we learned in childhood and usually is the result of going through treatments that taught us social skills or parenting, and socialization that taught us any time we did anything that made us happy or comfortable is wrong. We were taught to mask by growing up in a world in general that has sent us the message that all our natural behaviors are aversive.

We adapt to these messages, learn to hide all our natural impulses, and try to act in a way that makes other people less upset. I say "less upset" because my behavior still consistently upsets people. It just doesn’t upset them as much as it would if I were to stop masking. So, masking not only teaches us to hate any real part of ourselves, but it teaches us to keep human interaction superficial, lest we be discovered for the aliens we are.

One of my favorite writers about living as an adult with autism, Pete Wharmby, describes masking as the “conscious or subconscious effort that an autistic person makes to appear neurotypical to the people around them. It’s an intensely resource-intensive activity that is exhausting to maintain.”

In their article, Death by Suicide Among People With Autism: Beyond Zebrafish, South et al (JAMA, 2021) address the undiscussed epidemic of suicide amongst adults with autism. In it, they conclude that the act of masking is a significant contributor to our high suicide rates.

So when we are called high-functioning, it often invalidates how disabled we feel and how much we struggle to do daily living skills, mask, and maintain. It invalidates our life experience. It reminds us that what people want is for us to continue to appear normal and to continue to mask, despite the hardship masking forces us to endure.

As an autistic adult, I have never felt high-functioning. I feel like I am constantly fighting to maintain neurotypical expectations that are beyond me. I feel like a bat pretending to be a bird and failing, so every time someone says, “you are so high-functioning,” I want to scream. I am not high-functioning. I am exhausted and constantly overwhelmed and often covering up all the ways I am failing to meet neurotypical expectations.

The stigma of the "low-functioning" label

On the flip side of this, low-functioning labels can be just as destructive. Individuals perceived as low-functioning face stigmatization and isolation. Their strengths are ignored, and they are often treated as incapable.

I have several clients that are almost incapable of verbal communication but are excellent writers. We write our sessions out. They are perceived as “low-functioning” because they don’t talk and their facial expression is almost always flat or inappropriate, but if you take the time to try to communicate with them, they have a rich inner world that is often completely misunderstood.

Three levels of support

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5th Edition Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) does diagnostically put people with autism into three categories based on their needs for support. This seems more palatable to me. At level 1, we need some support. We need help with daily functioning and tasks but are able to do much on our own. At level 2, we need substantial support, and at level 3, we need very substantial support.

These levels don’t imply why you may or may not need support; they only acknowledge that support is needed at different levels depending on how your disability manifests. You are never high- or low-functioning. You just need different amounts of help with different tasks.

Autism as a wheel instead of a spectrum

Most of us with autism prefer that the spectrum be looked at as a wheel instead of a linear gradation of high and low functioning. We don’t like being called “a little bit autistic” or “profoundly autistic.” We prefer being seen as humans with different needs and wants.

The wheel of autism spectrum acknowledges and understands that some of us might struggle more with anxiety and sensory aversions and might talk too much and at the wrong time, while others might never talk, stim constantly, and be paralyzed by depression and sensory aversions. Others might be a little of all these things. The spectrum isn’t a line going from very autistic to a little autistic. It is a spectrum of traits that we all have to varying degrees. It is a spectrum that acknowledges that we all struggle and need help and that high-functioning is a myth and low-functioning is stigmatizing.

For most of the history of autism, the voice of autism has been parents and researchers. They liked functioning labels. Most of us do not. We prefer to be seen as unique individuals that should be understood for our struggles and our successes.

To me, autism is a disability. I have battled with it my entire life. I have lost friends and jobs because of it. I can’t read basic social cues, and this is problematic in almost every aspect of life. Functioning labels invalidate my disability and invalidate us as the unique humans we are.

References

South et al. (2021). Death by suicide among people with autism: Beyond Zebrafish. Journal of American Medical Association. Jan 4;4(1) e2034018

Wharmby, Pete (Twitter Feed). 2022