Artificial Intelligence

The Artistic Side of Artificial Intelligence

Move over selfie, AI might just be creating your world-class portrait.

Posted March 22, 2017

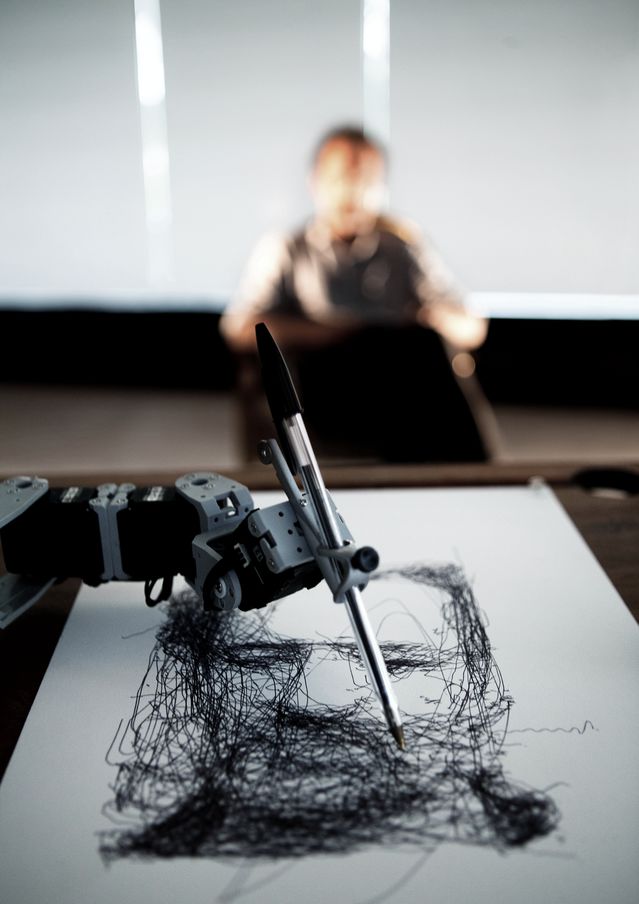

Meet Patrick Tresset, a London-based artist. His art practice follows two main paths. On one hand, Tresset presents theatrical installations in which robotic agents are actors. He also crafts the computational systems driving the robots so that their behavior can be perceived as artistic, expressive and even obsessive. These systems are influenced by research into actual human behavior—more specifically, how humans make marks or draw, how humans depict other humans, how humans perceive artwork, and how humans relate to robots.

Originally a painter, Tresset is part of a generation of artists coming out of Goldsmiths College's computing department. In 2004 Tresset joined Goldsmiths for an MSc degree in Arts Computing where from 2009 to 2012 he co-directed the AIkon-II project, which aimed to model and understand the sketching process. He also developed and taught the creative robotics module at Goldsmiths. In 2013 Patrick was a Senior Fellow at the Zukunftskolleg, University of Konstanz working with Prof. Deussen. Tresset has published research papers in the fields of computational aesthetics, social robotics, drawing research and AI.

Here's where it gets really interesting. Tresset also uses robots and computational systems to produce artworks on paper and canvas. And perhaps to the chagrin of Impressionists, he has created museum-quality art that evokes both thought and emotion. And it's this emotional manifestation—by the computer artist, subject, and viewer—that caught my attention.

I asked Tresset a few questions about his work and the future of technology's expressive side.

John Nosta: How did you start using a computer to create images?

Patrick Tresset: Originally, it was purely artistic research. In 1999, when I was still a painter, I started thinking about how to make machines produce drawings. I had lost my passion for making art, leading me almost naturally to explore the possibilities of machines doing what I no longer wanted to do. What first motivated my research is the underlying biographical element of my work and the robots. The robots can also be seen as being some form of self-portraits. I realized rapidly that to get interesting or truthful results, processes have to be simulated. Rather than trying to get a precise or premeditated result, it would be better to simulate processes such as perception, motor control, feedback, etc. and see what happens.

Nosta: How much is it purely the computer and how much is you?

Tresset: Well, l I am the author of the work, in one way or another. I am behind it and I evaluate it as if it is my own. I exhibit a lot my drawing robots—they now have done more than 14,000 drawings of people. I always work on the system that drives the robot. Each time I exhibit, I spend a fair amount of time "re-tuning" the systems until they produce results that I find interesting. The way I have designed and programmed the system isf for the robot to produce drawings that are true to them—drawings which are not pastiche of human ones. So the robots draw with a technique similar to the one I was using when I was drawing, but the style of the sketches is influenced by the robots' characteristics, limitations, and qualities. That said, I can never predict what the outcome of a session will be. I am still always surprised by the drawing produced.

Nosta: Would it be fair to call this process artificial intelligence?

Tresset: The term artificial intelligence is meaningless, or more precisely its meaning is fluctuating. Some people qualify this as artificial intelligence, I would not. I prefer to consider AI as a field of research, not as a thing.

Nosta: Has this technique provide any new insights into the subject that surprised you?

Tresset: Actually it's provided more insights into the drawing practice. A significant aspect to my practice is the exhibition of installations where robots are performers. I always find the way humans react to robots fascinating.

Nosta: Can we apply a "Turing Test" to art?

It has been done, including with my work. In the context of art, it would have to be done with experts. The Turing test only evaluates the appearance of things—as long as the system can fool humans it is successful. There are no systems where the author is not human, and as such there is no artwork where the system is the author. In a certain way, there are no fully autonomous systems in existence as there is always a "designer" who has made decisions during the system's research and development, and these decisions have, in one way or another, an impact/influence on the output or on the systems' behavior.

Nosta: Will computer and human art someday stand side by side in museums?

It is already the case: There are a number of artists who use computational technologies as a medium and who are exhibited in galleries and museums, including me. My robot drawings are purchased by art collectors, and there are some in a couple of public collections and in a lot of private collections.

---

Patrick’s work has been internationally exhibited in solo and group shows, in association with major museums and institutions such as The Pompidou Center (Paris), Tate Modern (London), Museum of Israel (Jerusalem), Prada Foundation (Milan), Victoria & Albert Museum (London), Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (Seoul), Bozar (Brussels), Laznia Center (Gdansk) and other events such as Art Brussels, Ars Electronica, Update_5, London Art Fair, Kinetica Art Fair and Istanbul Biennial. If you're interested in more information, a book is currently available that is published in Polish and English.