The flow state, a concept first recognized and analyzed by positive psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi in his book, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, is a worthy goal for anyone who wants to think and live more creatively. Really, who wouldn’t want to regularly find themselves in a flow state, in which the world falls away, and they have a single-minded focus on whatever task is at hand?

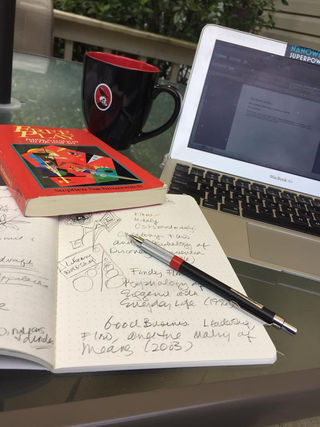

In my composition classrooms, I often have students "freewrite" about whatever topic we’re focusing on that day. I find that while they’re freewriting, they enter a state of flow. They just write, and write, and write. I give them this space, allowing the flow to happen. And I feel, during these moments in the classroom, the pressure and tension of their everyday lives fall away. It’s just them, their pencils or pens, their paper, and the flux and flow of their own minds.

This is an especially valuable state because it’s then that creative connections are made. The mind allows itself to think, without the constraints and expectations of the external world. There’s time enough later to look at what we’ve written while in a flow state, but it’s important to be able to stay there for as long as possible in order to reap the benefits from it.

According to Csikszentmihalyi, flow states have several key characteristics. They involve intense concentration, a merging of action and awareness, a loss of reflective self-consciousness, a sense of personal control over the activity, a distortion of the awareness of time, and an experience of the activity as intrinsically rewarding.

I find myself slipping into flow states with many different activities—writing, reading, gardening, playing music, playing games, meditating, and doing yoga. I’ve come to appreciate the circumstances that I need to allow for myself in order to experience flow. Flow doesn’t just happen—I must set myself up for it, giving myself the time and space and permission needed to focus solely on a task at hand.

In our era of multiple distractions, it can be difficult to slip into a flow state. Often, in the middle of doing something – when I might actually be in a flow state – I stop to check my phone or my email or search the web, and those activities break it up. More even than when Csikszentmihalyi first theorized about flow, we’re in great need of it today. And it’s important to be aware of the ways we sabotage our own flowing. The phone can wait. The emails can wait. Even the Google searches, often, can wait. Let’s sit with ourselves, our minds, and our energy, and see where we go. We might be surprised by what—and who—we find.

Of all the experiences associated with flow, the one that most intrigues me is how my sense of time changes. It’s almost as if time itself stops, warps, or alters. The magic in this is that, while flowing, time seems to slow down, and I’m able to be more productive in less time. When I’m not flowing, time speeds by, and I can’t seem to accomplish much of anything. In a flow state, however, I’m many times more productive than I am outside of it. Time opens up, slows down, gives space. It truly is a kind of magic circle.

So how can we create spaces for flow in our own daily lives? The first step is to recognize the importance of flow, to value it. Once we value something, we make time for it. We put it on our to-do list. We find ways to fit it into our everyday lives.

Then, it’s important to schedule it—even if it means just setting aside ten minutes. Those ten minutes, flowing, are going to be much more meaningful than ten minutes surfing the web or scrolling through social media. Scheduling time to flow is a way of honoring it, a way of telling ourselves not just that it matters, but that it matters enough to give it its own time and space.

Next, it’s important to decide on an activity. It can be anything that we find intrinsically valuable, since that intrinsic value is important to inducing flow. It’s nearly impossible to flow doing something we don’t want to do. Even if it’s something we have to do, however, we can look for a component of it that can potentially induce a flow state—some part of it that we enjoy or value in itself. Maybe we don’t want to go through the drudgery of making up a budget, but we find freewriting about our values, what we want and need, can be flow-inducing. Look for those activities that you enjoy, that you want to do, and that you find intrinsically rewarding. It might be pulling weeds in the garden. It might be watercolor painting. Anything that we love is fair game.

Finally, just do it. Set a timer, if necessary, but throw yourself wholeheartedly into the activity for the time you have. Don’t second-guess yourself. Don’t worry about what else you have to do. Don’t backtrack. Don’t think about the future. Just be in the present moment, focusing intently on the activity at hand.

And that’s it. That’s flowing. It’s both simple and powerfully complex at the same time. It’s a beautiful, mysterious process—one that will change your life for the better and bring in a daily dose of creativity. And during those moments of flow, you’ll find yourself making connections, forming ideas, and thinking differently. All of these benefits will accrue effortlessly, as well, because that’s the whole thing about flow: It feels effortless. That’s its magic. And it has extraordinary potential for helping us remake our lives and the world.

References

Csíkszentmihályi, Mihály. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. NY: Harper & Row.