Narcissism

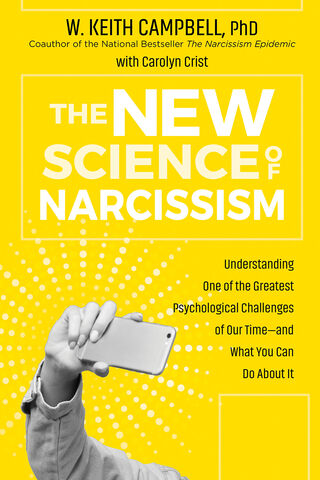

The New Science of Narcissism

W. Keith Campbell and Carolyn Crist talk to The Book Brigade.

Posted December 4, 2020

Everyone distorts the world to some degree. Narcissists do it in a very distinctive way to protect themselves. Even so, it turns out, not all narcissists are alike.

What is the new science of narcissism?

The new science of narcissism represents research from recent years in personality and clinical science—as well as allied academic disciplines— focusing on the definition of “narcissism” itself and how it manifests.

How does it differ from the old science of narcissism?

Until relatively recently, the research around narcissism was hampered by tremendous misunderstanding and debate among researchers and clinicians. Most prominently, there were two different definitions of narcissism being used under the same name. As a result, you could have somebody who was bold and audacious and somebody who was shy and insecure, and both could be described under the same label of “narcissist.”

What are the origins of this new science?

One important force was the development and redevelopment of sophisticated personality measures of narcissism. When research teams started building more precise measures, they found that the measures didn’t line up the way they were “supposed to” theoretically. It turned out there were two psychological traits that had some similarities with really important differences. With new models, we now label them as two different types—grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism.

What do you find that people misunderstand most about narcissism?

One of the biggest confusions out there is that people think “narcissism” often refers to a personality disorder or a clinical syndrome. More often, though, when people talk about narcissism, they’re actually describing a personality trait. In reality, we all have some level of narcissistic traits—some more and some less. At the same time, there is a personality disorder called Narcissistic Personality Disorder, which reflects an extreme and inflexible form of narcissism. This disorder is hampering but also relatively rare, existing in perhaps 1 percent or 2 percent of the population. We want to help people understand narcissism on the trait level.

What got you interested in studying narcissism in the first place?

All of us distort the world around us or information that has to do with ourselves. Most of us think we’re better drivers than we are. Most of us think we’re more attractive than the average person. This is something psychologists have known for over a century. What fascinates us about narcissism is that some people—those with high levels of narcissism—have a strong and well-defined ability to distort the world around them in a way that makes them look good. By understanding narcissism, we can then more fully understand the way the ego works for everybody.

How did American culture get so focused on narcissism—and is that focus unique to the U.S.?

The interest in narcissism has come in waves. People got interested in it when social media appeared, then when selfies became popular, and then again around reality TV and celebrities. People have also become interested in narcissism related to darker trends as well, such as school shootings, terrorism, and political leadership. Unfortunately, narcissism is an evergreen issue found all over the world, but U.S. culture is seen as particularly narcissistic, both by U.S. citizens and people around the world. People see Americans as particularly brash and self-centered but also social and entertaining.

Donald Trump is sometimes referred to as the narcissist-in-chief. To what degree is he exhibit A of narcissism?

We’ve done research looking specifically at perceptions of Trump’s personality. Importantly, we’ve asked people who supported the president, as well as people who didn’t support him, to rate his personality. Overall, both supporters and detractors see his personality structure as being largely narcissistic. He is bold, confident, assertive, and combative interpersonally. He’s certainly someone who holds a high opinion of himself.

However, supporters see his narcissism as somewhat prosocial or pro-national—someone who is fighting for them. In contrast, detractors see him as psychologically unstable and impulsive, with a more pathological and dangerous form of narcissism that leads him to act only in his own interests and against the interests of the country. In the end, Trump’s narcissism is probably consistent with other former presidents such as Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard Nixon, and John F. Kennedy.

In research you’ve done on narcissism, what finding has surprised you the most?

What has really been surprising—a finding that came about somewhat recently—is that people who are narcissistic can see their narcissism, especially interpersonally, with antagonism and their sense of entitlement as somewhat detrimental to their own life. Before this, researchers, clinicians, and psychoanalysts thought narcissistic people largely enjoyed their character structure and didn’t really see any need to change. Instead, there does seem to be (in some cases) some acknowledgment that there’s a cost to self-centeredness. This new finding is a good example of why the new science of narcissism is important. We can uncover findings like these using empirical research in a way that you won’t see when relying on intuition.

Are narcissists born or made? And if they’re made, is there a critical ingredient?

There’s been a lot of research looking at the question of how much of personality is inherited versus environmentally shaped, and a reasonable amount of research has focused specifically on narcissism. Overall, about 60 percent of narcissism, like many traits, is inherited. That means it’s probably linked to a complex array of genes.

About 30 percent of what predicts personality traits, including narcissism, comes from the non-shared environment, or the individual experiences that people have and the people they encounter in life. About 10 percent seems to be linked to parenting, which is not as much as most people would predict. In terms of parenting, there’s a split: Grandiose narcissists tend to say they had parents who were permissive and perhaps over-praising, and vulnerable narcissists had parents who were cold and even hostile.

What damage do narcissists do—to themselves and/or to those around them?

Narcissists damage themselves and people around them in an important order. First, the damage done by narcissists happens in their social group. Narcissists can be exploitive in work relationships, unfaithful in romantic relationships, and dishonest in business relationships. In the short term, all of that hurts other people but benefits the narcissist.

However, over time, people grow to dislike the narcissist and leave the relationship. As a result, people who are narcissistic are constantly in search of new partners to take advantage of, manipulate, and exploit.

Is there an upside to narcissism?

Yes. Narcissism—particularly grandiose narcissism—is really a tradeoff. The benefits are seen in the short term and in public. Narcissism is good for public speaking, meeting people, emerging as a leader in groups, getting dates, and gaining followers on social media. It’s important to realize that narcissism has real benefits and real costs in order to fully understand it.

What is the single most important point you want to get across about narcissism?

Everyone can have a solid understanding of narcissism by understanding the science. That knowledge is always growing, changing, and getting better. We shouldn’t spend time fighting over what’s right or wrong in the field, but instead, work together to find even better measures and models for understanding narcissism and the world.

About THE AUTHOR SPEAKS: Selected authors, in their own words, reveal the story behind the story. Authors are featured thanks to promotional placement by their publishing houses.

To purchase this book, visit: The New Science of Narcissism.