Sleep

Sleep Loss Disrupts Emotional Balance via the Amygdala

Insomnia makes the amygdala unable to regulate emotions with neutrality.

Posted December 9, 2015

We all know the feeling of being cranky, volatile, and emotionally sensitive after a poor night of sleep. Until now, the neural mechanisms that tamper with our emotions when we haven’t gotten enough sleep have been mysterious.

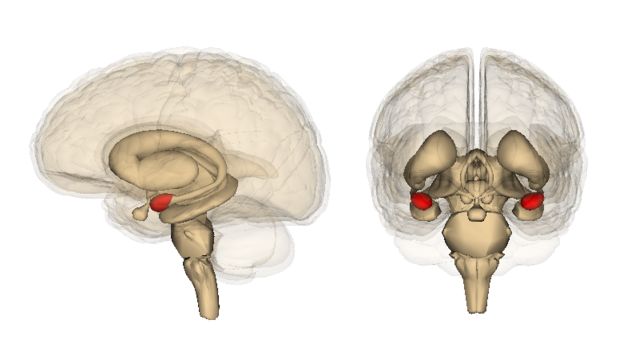

In a recent study, researchers at Tel Aviv University (TAU) identified that heightened activation of the amygdala is responsible for disturbing emotion regulation and increasing anxiety from lack of sleep. The researchers found that just one night of sleeplessness changes your ability to regulate emotions and allocate brain resources necessary for objective cognitive processing.

The Amygdala Tampers with Emotional Control When You're Tired

The December 2015 study, “Losing Neutrality: The Neural Basis of Impaired Emotional Control without Sleep,” was published in the Journal of Neuroscience. The research was led by Professor Talma Hendler of TAU's Sagol School of Neuroscience, and conducted by TAU graduate student Eti Ben-Simon at the Center for Brain Functions at Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center. In a press release, Hendler said,

"Prior to our study, it was not clear what was responsible for the emotional impairments triggered by sleep loss. We assumed that sleep loss would intensify the processing of emotional images and thus impede brain capacity for executive functions.

We were actually surprised to find that it significantly impacts the processing of both neutral and emotionally-charged images. It turns out we lose our neutrality. The ability of the brain to tell what's important is compromised. It's as if suddenly everything is important.”

For this study, Ben-Simon kept 18 adults awake all night to conduct tests while undergoing brain mapping (fMRI and/or EEG). First following a good night's sleep and the second following a night lacking any sleep.

One of the tests required participants to describe in which direction small yellow dots were moving over distracting images. These images were labeled as: "positively emotional" (a cat), "negatively emotional" (a mutilated body), or "neutral" (a spoon).

Participants who had a good night's rest, were able to identify the direction of the dots hovering over the neutral images faster and more accurately, and their EEG pointed to differing neurological responses to neutral and emotional distractors. When sleep-deprived, however, participants performed badly in the cases of both the neutral and the emotional images. This implied decreased emotional regulatory processing.

A second experiment tested concentration levels. For this study, participants were shown neutral and emotional images while performing a task demanding their full attention and were told to ignore distracting background pictures with emotional or neutral content. This time researchers measured activity levels in different parts of the brain as they completed the cognitive task using an fMRI scanner.

After only one sleepless night, participants were distracted by every single image (neutral and emotional). Conversely, well-rested participants were only distracted by emotional images. This effect was indicated specifically by activity changes in the amygdala, a brain region that plays a role in emotional processing. Hendler concluded,

"We revealed a change in the emotional specificity of the amygdala, a region of the brain associated with detection and valuation of salient cues in our environment, in the course of a cognitive task.

These results reveal that, without sleep, the mere recognition of what is an emotional and what is a neutral event is disrupted. We may experience similar emotional provocations from all incoming events, even neutral ones, and lose our ability to sort out more or less important information. This can lead to biased cognitive processing and poor judgment as well as anxiety."

Do You Suffer From Sleep Deprivation or Insomnia?

Humans have evolved to spend roughly one-third of our lifetime sleeping. Ideally, you should sleep about 8 hours a night, which adds up to 122 days of sleep per year. Your mind, body, and brain will function optimally at a basic two-to-one ratio of wake-to-sleep. For every two hours you're awake, you need about one hour of sleep. By the time you are sixty years old, this would add up to twenty years spent sleeping, and about five solid years in REM (rapid eye movement sleep).

If you suffer from sleepless nights or insomnia, you are not alone. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 30 percent of American adults get less than six hours of sleep per night. What are your patterns of sleeplessness?

An October 2015 SLEEP study, “The Effects of Sleep Continuity Disruption on Positive Mood and Sleep Architecture in Healthy Adults,” from Johns Hopkins University, found that waking up several times throughout the night is more detrimental to people's positive moods than getting the same shortened amount of sleep without interruption.

The Johns Hopkins' researchers said that those who were forced to awaken had a reduction of 31 percent in positive mood, while the delayed bedtime group had a decline of only 12 percent. These new findings on the importance of continuous sleep illuminate the vital role sleep plays in maintaining a positive emotional balance in our daily lives.

The researchers are currently examining how novel methods for sleep intervention (mostly focusing on REM sleep) may help reduce the lack of emotional regulation seen in anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD).

Conclusion: Sleep Deprivation Is a Modern Day Epidemic

As a modern society, we are sleeping less and less every year. Digital devices have been found to throw off our circadian rhythms and trigger sleep disturbances. As a simple rule of thumb, avoiding digital devices in the hour before bedtime could help you get a better night's sleep.

Of course, the financial squeeze so many Americans feel due to low paying jobs, and minimum wage set at poverty levels, can leave less hours in the day for sleeping. Socio-economic stratification often makes sleep deprivation a daily reality beyond a low-income person's locus of control. As people struggle to pay bills, juggle family obligations, and try to find time for exercise—sleep becomes the first disposable commodity to go. This is a dangerous trade off.

Unfortunately, sleep deprivation is unavoidable for millions of Americans who are underpaid and overworked. That said, if you'd like some practical tips for getting a good night’s sleep, you can read a preview of my chapter, "The Sleep Remedy” from The Athlete's Way for free on Google books.

To read more on this topic, check out my Psychology Today blog posts,

- "How Do Sleeplessness and Insomnia Sabotage Decision Making?"

- "Sleep Strengthens Healthy Brain Connectivity"

- "Neuroscientists Discover How the Brain Learns While We Sleep"

- "Power Naps Help Your Hippocampus Consolidate Memories"

- "Insomnia Creates a 24-Hour Brain Condition"

- "Two Simple Ways to Help Children Sleep Better"

- "Why Is a Camping Trip the Ultimate Insomnia Cure?"

© 2015 Christopher Bergland. All rights reserved.

Follow me on Twitter @ckbergland for updates on The Athlete’s Way blog posts.

The Athlete’s Way ® is a registered trademark of Christopher Bergland.