Adolescence

Why Is the Teen Brain So Vulnerable?

Researchers have discovered a gene linked to healthy teenage brain connectivity.

Posted December 19, 2013

During adolescence, the teen brain goes through dramatic changes which scientists are just beginning to better understand. For parents, teachers, and anyone who cares for a teenager—it is often difficult to help a teen navigate the broad range of challenges that accompany the complex changes occuring in the body, mind, and brain.

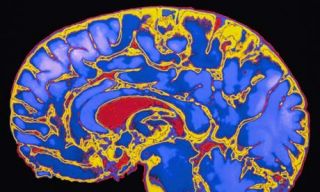

Why is the teen brain so vulnerable and volatile? During early- and mid-adolescence, the brain undergoes considerable neural growth and pruning which create changes of connectivity within and between various brain regions. This transition is riddled with many potential minefields and booby traps for most teenagers.

By some estimates, human brain development and connectivity is not fully completed until about the age of 25. Some researchers have pointed out, "the rental car companies have it right." The brain isn't fully mature at 16, when a teenager can get a driver’s license; or at 18, when we are allowed to vote; or at 21, when we are allowed to drink, but closer to 25, when we are allowed to rent a car.

The Teenage Prefrontal Cortex Is Highly Malleable

Teenage brain structure, connectivity, and behavior are all intertwined. While young adults are advancing to new levels of sophisticated thinking and emotional regulation, their brains are simultaneiously undergoing changes directly needed to support these functions.

The most widely studied changes in the teenage brain take place in the prefrontal cortex, which is the area behind the forehead and associated with planning, problem-solving, and other 'executive functions.' Healthy brain development and connections require a streamlining combination of brain plasticity, which fortifies certain connections so signals can be transmitted more efficiently, and synaptic pruning, which causes other connections to atrophy.

During healthy teenage brain development the prefrontal cortex communicates more fully and effectively with other parts of the brain, including ares particularly associated with emotion and impulses. The cluster of functions that center in the prefrontal cortex is sometimes called the "executive suite," including calibration of risk and reward, problem-solving, prioritizing, thinking ahead, self-evaluation, long-term planning, and regulation of emotion.

Two recent studies have found that dopamine and cortisol levels—along with a gene called DCC—are part of a chain reaction that dramatically influences teenage development and connectivity of the prefrontal cortex.

The DCC Gene Regulates Prefrontal Cortex Connectivity

In a breakthrough discovery published on December 17, 2013 researchers at the Douglas Institute Research Centre, which is affiliated with McGill University, have isolated a gene called DCC which may be responsible for healthy brain connectivity during adolescence. The researchers believe that slight variations in DCC during adolescence can produce significant alterations in prefrontal cortex function later in life. The findings were reported in the journal Translational Psychiatry.

DCC is directly linked to the dopamine network in the prefrontal cortex during adolescence. Working with mice models, the researchers found that dysfunction of this gene during adolescence has behavioral consequences that can carry into adulthood.

Parents of children who develop mental illness tend to notice the first symptoms of "something not quite right" with their children begin to appear during the teen years. It is known that during this teenaged phase of brain development, adolescents are particularly vulnerable to psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, depression and drug addiction.

To determine whether the findings of such basic research can translate to human subjects, researchers examined DCC expression in postmortem brains of people who had committed suicide. In a dramatic finding, teenagers who committed suicide showed levels of DCC expression that were 48 percent higher than in control subjects.

"The prefrontal cortex is associated with judgment, decision making, and mental flexibility—or with the ability to change plans when faced with an obstacle," explained Cecilia Flores, senior author on the study and professor at McGill's Department of Psychiatry. She adds, "Its functioning is important for learning, motivation, and cognitive processes. Given its prolonged development into adulthood, this region is particularly susceptible to being shaped by life experiences in adolescence, such as stress and drugs of abuse. Such alterations in prefrontal cortex development can have long term consequences later on in life."

The breakthrough discovery of DCC provides more clues towards a better understanding of this volatile phase of teenage brain development. Dr. Flores said, "Certain psychiatric disorders can be related to alterations in the function of the prefrontal cortex and to changes in the activity of the brain chemical dopamine. Prefrontal cortex wiring continues to develop into early adulthood, although the mechanisms were, until now, entirely unknown."

By identifying the first molecule involved in how the prefrontal dopamine system matures, researchers now have a target for further investigation for developing pharmacological and other types of therapies. "We know that the DCC gene can be altered by experiences during adolescence," said Dr. Flores. "This already gives us hope, because therapy, including social support, is itself a type of experience which might modify the function of the DCC gene during this critical time and perhaps reduce vulnerability to an illness."

According to the researchers the psychiatric consensus is that early therapy and support in adolescence, as soon as a mental health issue first manifests itself, has dramatically greater potential for a successful outcome—and for a healthy and happy adulthood.

Teenage Stress Raises Cortisol and Lowers Dopamine Levels

In another study from January 2013 Johns Hopkins researchers established a link between elevated levels of the stress hormone cortisol in adolescence that triggered genetic changes that, in young adulthood, that can result in mental illness in those predisposed to it. The recent discovery of the DCC gene dovetails with these earlier findings.

The findings were reported in an article titled, “Adolescent Stress-Induced Epigenetic Control of Dopaminergic Neurons via Glucocorticoids," published in the journal Science. These findings could have wide-reaching implications in both the prevention and treatment of schizophrenia, severe depression and other mental illnesses.

The investigators at Johns Hopkins found that the "mentally ill" mice had elevated levels of cortisol which becomes elevated as part of the body's fight-or-flight response. They also found that these mice had significantly lower levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine in a specific region of the brain involved in higher brain function, such as emotional control and cognition. Changes in dopamine in the brains of patients with schizophrenia, depression and mood disorders have been suggested in clinical studies, but the mechanism for the clinical impact remains elusive.

"We have discovered a mechanism for how environmental factors, such as stress hormones, can affect the brain's physiology and bring about mental illness," says study leader Akira Sawa, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "We've shown in mice that stress in adolescence can affect the expression of a gene that codes for a key neurotransmitter related to mental function and psychiatric illness. While many genes are believed to be involved in the development of mental illness, my gut feeling is environmental factors are critically important to the process."

Sawa, director of the Johns Hopkins Schizophrenia Center, and his colleagues simulated social isolation associated in mice that would parallel the difficult years of adolescents in human teens.The team found that isolating healthy mice from other mice for three weeks during the equivalent of rodent adolescence had no effect on their behavior. But, when mice known to have a genetic predisposition to characteristics of mental illness were similarly isolated, they exhibited behaviors associated with mental illness, such as hyperactivity.

They also failed to swim when put in a pool, which is an indirect correlate of human depression. When the isolated mice with genetic risk factors for mental illness were returned to group housing with other mice, they continued to exhibit these abnormal behaviors, a finding that suggests the effects of isolation lasted into the equivalent of adulthood.

"Genetic risk factors in these experiments were necessary, but not sufficient, to cause behaviors associated with mental illness in mice," Sawa says. "Only the addition of the external stressor—in this case, excess cortisol related to social isolation—was enough to bring about dramatic behavior changes."

Conclusion: Environmental Factors and Daily Habits Influence Teen Brain Connectivity

Akira Sawa says the new study points to the importance of finding better preventive care in teenagers who have mental illness in their families, including efforts to protect them from social stressors, such as isolation and neglect. Meanwhile, by understanding the cascade of events that occurs when cortisol levels are elevated, researchers may be able to develop new compounds to target tough-to-treat psychiatric disorders.

From a positive psychology perspective, there is growing evidence that creating safe, loving and nurturing environments throughout a child’s life has profound effects on healthy brain development that can take teens north-of-zero.

Also, encouraging daily habits that reduce cortisol and increase dopamine and oxytocin is crucial. This includes lifestyle choices like: fortifying intimate bonds, maintaining extensive social networks, having creative outlets, regular physical activity, mindfulness, not abusing drugs and getting a good night’s sleep. These daily routines will help to optimize healthy brain structure and connectivity for a teenager and througout adulthood.

If you’d like to read more on this topic, check out my Psychology Today blog posts:

- “Cortisol: Why “The Stress Hormone’ Public Enemy No. 1”

- “Heavy Marijuana Use Alters Teenage Brain Structure”

- “Can Physical Activities Improve Fluid Intelligence”

- “Maternal Care in Early Life Boosts Resilience into Adulthood”

- “Meditation Has the Power to Influence Your Genes”

- “Brain Connectivity Varies Between Men and Women”

- “Unique Gene Combinations Reshape Our Brains and Behaviors”

- “The Size and Connectivity of the Amygdala Predicts Anxiety”

- “One More Reason to Unplug Your Television”

- “Sleep Strengthens Healthy Brain Connectivity”

- “Social Connectivity Drives the Engine of Well-Being”

Follow me on Twitter @ckbergland for updates on The Athlete’s Way blog posts.