Sex

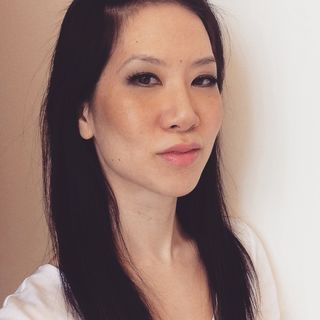

Sex Researcher Turned Journalist Challenges Sexual Dogmas

Sexologist Debra Soh's work challenges sexual dogmas and political correctness.

Posted September 25, 2017 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Debra W. Soh writes about the science of sex and its politicization. She is a columnist for Playboy and the Globe and Mail. Her writing can also be found in Harper's, the Wall Street Journal, the Los Angeles Times, CBC.ca, Scientific American, the Chicago Tribune, Newsday, New York Magazine, Men's Health, the Independent, the Weekend Australian, Quillette, the Korea Herald, Salon, and Pacific Standard.

Debra holds a Ph.D. in sexual neuroscience from York University and was awarded the Provost Dissertation Scholarship for her fMRI research on paraphilias and hypersexuality. She is a recipient of the prestigious Michael Smith Foreign Study Award from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and has published in academic journals including Archives of Sexual Behavior and Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

Q: You are truly a maverick, in that you are a legit Ph.D. researcher specializing in sexuality, who also happens to write prodigiously for what seems like every major English speaking publication, including New York Magazine, Playboy, LA Times, and The Wall Street Journal. Before I ask about specific topics, can you say a bit about how you became interested in the field of sexology and then how you have seemingly decided to apply your academic training to journalism?

A: Thank you! Well, I first became exposed to sex research during my undergraduate degree. At the time, I didn’t realize such a field even existed; back then, sexology wasn’t featured as prominently in mainstream media, which is something that has thankfully changed. I was interested in doing a combination of neuroimaging and sexological research and was able to pursue this in graduate school.

During my Ph.D., I began writing about political issues within sexology; specifically, gender dysphoria in children. I felt the public discussion on this topic was biased and there was a need for the other side—the one backed by scientific research—to be heard.

I was extremely lucky in that my mentors and graduate school advisors were supportive of my writing. They have encouraged me, from day one, to always speak the truth, no matter how politically incorrect it may be. But I am aware that other institutions don't necessarily feel the same way. The climate has changed considerably in recent years. So I made the decision to leave academia so that I could write and speak openly about issues in the field.

Q: You certainly don't shy away from controversy; indeed, you seem to crave it, a characteristic which holds a soft spot in my heart. In your articles, you touch upon everything from sexuality to politics to social justice to political correctness. I would say it takes a lot of nerve and courage to openly and directly tackle some of these subjects. This is a bit of a multi-tiered question, but how do you choose your topics, what do you hope to accomplish, and what kind of response have you received?

A: I write about topics that have a presence in the news, particularly if the discussion is biased in a scientifically incorrect way. My hope is to offer some balance to the discussion and possibly expose people to information they might not otherwise encounter.

The response I receive is usually very positive. People are often relieved that someone has publicly said what they’ve been silently thinking but weren’t able to say, due to political correctness or fears of being ostracized by other people. Sometimes, the things I write about upset people, but I have pretty thick skin, so the backlash doesn’t bother me.

Q: A recurring theme of your work is the growing discrepancy between science and social activism. You wrote several LA Times op-ed pieces earlier this year criticising, in turn, the gender-neutral parenting movement, "gender feminists," and trans activists for ignoring neuroscience research on brain differences between the sexes. In Playboy, you state that science around biological differences has become too politicised. You lay it on thick with the research evidence; agree or disagree, the scientific evidence is certainly compelling. You make it clear that all of these groups have good intentions, but why do you think this science-activism gap keeps ever expanding? Why the seemingly willful ignorance?

A: I think part of the problem is that many people don’t actually know the scientific literature on this topic or how the scientific method works. If you know the research literature, you know that these brain differences are real. I have had a number of people reach out to me to tell me privately that they know the research is legitimate, but they deny it because they’re afraid it will be used to justify sexism.

So, some people are intentionally misrepresenting the research, and others, like you said, remain willfully ignorant. It’s much easier to wave your hand and dismiss the whole thing as “pseudoscience” or repeat the same five criticisms of the field over and over again than to take the time to read the articles and come to your own conclusions. We don’t need to deny the science in order to have gender equality.

Q: The issue around sex differences recently came up again with the whole James Damore Google manifesto controversy, which you wrote about in the Globe and Mail. You state the science supported Damore's claims, yet everyone in the media went nuts about it, often misrepresenting the actual memo and without providing an opportunity for readers to actually see the original source material. The entire coverage and response seemed disingenuous, like they wanted to destroy this guy. What do you think was going on?

A: What you say is very true—the links Damore included in his original memo were stripped from the first published version, and the coverage didn’t accurately reflect its contents. I doubt many of the outraged who criticized him had even read the memo.

When I look at how the entire thing unfolded, it’s extremely disappointing, especially considering how outlets that purport to be about science and technology were dismissing the science in favor of promoting a particular political agenda. As a woman with a Ph.D. in a STEM discipline, of course, I don’t think discrimination against women is acceptable. But we need to be able to have rational discussions about these issues, instead of seeing them as threatening and simply shutting the whole thing down. The DDoS attacks on Quillette’s site, which were for the purpose of censoring us, were particularly concerning.

Q: Let's talk about your article on sex robots. I am particularly interested in how new technology such as virtual reality and artificial intelligence will change the way people engage in relationships and sexuality in the future. You seem to think that these technologies will bring about positive effects. Specifically, I am most interested in the harm reduction aspect of my clinical work as a sex therapist, and you believe that sex robots can help those with atypical sexual interests to find an outlet. Could you briefly tell us more about what you imagine that may look like? You seem, for example, to think that mental health professionals could dispense childlike sex dolls to pedophiles as a means of preventing them from acting out, is that something that could realistically be adopted in the US or Canda?

A: I believe sex dolls could be useful in the context of harm reduction, but we’d need the data to confirm this. If studies in the future did find that child-like sex dolls helped to prevent pedophilic men from offending against children, I think the next logical step would be to include them in therapeutic interventions. As uncomfortable as the idea might make some people, if we are concerned about child safety, we should follow what the research tells us and advocate for prevention of abuse. Brain imaging studies I have worked on have shown that pedophilia is hard-wired and cannot be changed.

The issue is so fraught, I’m not sure if or when this will realistically happen. In the case of someone who is, say, sadistic, I don’t think a robot, no matter how realistic it is, would ever fully satisfy them, because they would know it’s a robot they are engaging with. But it would be the next best thing, and if it helps to improve public safety, then I think it’s a solution worth considering.

Q: There is always somewhat of a moral panic that arises from social and technological change, as I would argue that the whole sex addiction and porn addiction moral panics are a response to social changes brought on by the internet. What do you think will be some of the most hot-button issues arising from VR and AI adoption? I'm being somewhat sarcastic, but should we all start getting preventatively treated for virtual reality addiction?

A: From the feedback I’ve gotten, I sense the greatest concern right now is that VR and AI will replace real-life partners; that people will prefer to lock themselves in a room with the technology instead of going out and having sex with real people, or their spouses. For people who are emotionally healthy, however, I don’t see this happening.

I wouldn’t be surprised if we do start seeing treatment become available regarding "VR addiction." As VR and AI become more mainstream, I imagine that, for some people, their use may become problematic. But much like the issues we see around problematic porn use, it will be due to reliance on sex as a coping mechanism, as opposed to being a true addiction.

Q: Your most recent article in Playboy tackled the intersection between sexuality and political orientation. You mention personality implications and I agree that personality traits play a big part in both, and I've often wondered why the Five Factor Model is rarely touched upon when discussing these topics. For example, I think it's no surprise that liberals are shown to be more open to new experiences and so are more likely to be sexually adventurous. I found a few things about conservatives, however, to be quite surprising, specifically that they are more likely to be sexually satisfied and also engage in sex with sex workers. What do you think that is all about?

A: I think liberals, being higher in personality trait openness, may have a tendency toward searching for the next best thing, which may explain why they report being less sexually satisfied. Regarding why conservatives are more likely to engage in sex with sex workers, in my research and clinical experience, men tend to seek out sex workers if they are unable to find partners who are interested in having the kind of sex they are into (for example, if they have atypical sexual interests) or if their partner is less interested in having sex, due to having a lower sex drive or not wanting to unless it is for procreative reasons. More research would need to be done, but on a purely speculative level, I wonder if this might in part explain the study authors’ findings.