Trauma

Tattoos After Trauma: 6 Qualities of Healing Potential

While there are many reasons for tattoos, one is choosing a tattoo after trauma.

Posted July 18, 2021 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Tattoos offer six of the qualities associated with recovery from trauma.

- Tattoos literally heal from the body out by using the skin to narrate healing in words and images.

- Tattoos address the essential dilemma in trauma between hiding the unspeakable and proclaiming it.

Whether you have many tattoos or would never consider getting one, you may be surprised to learn that according to a 2019 IPSO poll, 3 in 10 (30%) of Americans have at least one tattoo and 40% under the age of 35 have at least one tattoo. That is an increase from 21% in 2012.

While the reasons for tattoos are as varied as the people who choose to get them, certain trends have been identified. One persistent theme is the choice of a tattoo to register some aspect of dealing with a traumatic event.

Across nations, generations, and wars, those in the military have used tattoos as symbols of allegiance, horrors faced, bravery, survival, and tributes to fallen comrades.

Recently confronted with the devastation of suffering and death from COVID-19, a team of ICU nurses chose to recognize their bond and their work by each getting a tattoo that symbolized the front line, the team, and the patients who died.

Do These Tattoos Have Healing Potential?

A close consideration suggests that tattoos—the reason, the choice of tattoo, and the experience of getting a tattoo—offer six of the qualities associated with recovery after trauma.

Remembering and Mourning

Not all loss is traumatic but all trauma involves loss. It may be the loss of loved ones, of life as it was known, of a sense of agency, safety, predictability, of hope.

Recovery from trauma involves both remembering and finding a place to deal with traumatic loss. Many find a place for unspeakable trauma and loss in tattoos.

In the aftermath of 9/11, civilians and firefighters throughout the world choose tattoos as an indelible reminder of the terrorist assault, the courage of first responders, and the loss of so many.

In recognition of the violent death of George Floyd, a tattoo artist offered discounted tattoos of the words, “I can’t breathe” “Black Lives Matter,” etc. The requests came flooding in as so many resonated with the horror and need to bear witness.

When a young father suffered the death of his newborn son, his brothers joined him in tattooing the name of their nephew on their arms. Together they would remember and carry him.

Healing From the Body Out—The Skin as Canvas

Whether a traumatic event involves a terrorist attack, sexual abuse, or facing death every day during a pandemic, it is registered in our body in terms of the survival reflexes of fight, flight, and freeze.

Encoded under these conditions, our memory of the traumatic event is not registered as narrative, but as fragments of highly charged visual images, bodily feelings, tactile sensations, or sensory reactivity to reminders of the event.

As such, trauma experts, like Bessel Van Der Kolk (2015), remind us that in the aftermath of trauma, The Body Keeps Score and we need to work “from the body out” in the course of recovery and healing.

" … you can’t fully recover if you don’t feel safe in your own skin.” (Van Der Kolk, 2014, p.218)

Tattooing starts at the body’s first line of defense, the skin, and uses it as a canvas to physically bear witness to the assault experienced on body, mind, and sense of self. As such, it often visually and viscerally becomes a source of healing.

A 24-year-old victim of sexual assault describes her body art as “… a visual reminder I am still alive. And still OK.” She adds, "If I am having a hard time, as soon as I touch my wrist and I run my finger over my word ‘survivor,’ it helps.”

Re-Defining Self

In her book Under the Skin; A Psychoanalytic Study of Body Modification, Allessandra Lemma (2010) reminds us that with tattooing, the significance for many is not just in the final creation but in the process of inking itself. For some, the process of the physical transformation, albeit painful, is like the birth of a new self depicted in images or words. The tattoo is a visual demarcation of the new self from the old.

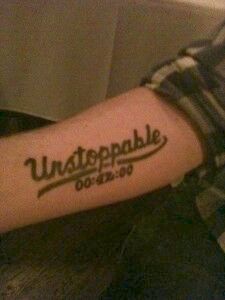

After a near-death experience, a young man chose to tattoo his inner arm with the word “Unstoppable” and “00:42:00”—the time he was flatlined.

Many women who have had a mastectomy as treatment for breast cancer are using tattoos to reclaim their physical and sexual sense of self.

Narrating Healing in Words and Images

Many speak of the tattooing experience as an opportunity to share, create, and symbolize aspects of their traumatic experience with the tattoo artist. The setting, the connection, the interest of the tattoo artist, and even the pain open a space for self-awareness, self-reflection, even transcendence.

Van der Kolk (2010, p.210) describes such self-awareness (often accessed through mindfulness, meditation, therapeutic massage, tai chi, etc.) as necessary to bridge the emotionally driven survival state of trauma and the cognitive ability to register what happened without reactivity.

From Judith Herman’s (1997) perspective, the essential dilemma of healing from trauma is the survivor’s conflict between hiding the unspeakable and proclaiming it. One might consider that tattooing addresses that dilemma.

To look at the variations, colors, intricacies, and images of tattoos is to recognize them as creative outlets of a healing narrative.

Undoing the Shame of Hidden Trauma

In its visibility and in the bearer’s wish to let it be seen, a tattoo can undo the shame so often associated with trauma, war, and victimization.

A Brazilian tattoo artist, Flavia Carvalho has a project, “A Pele da Flor” (The Skin Of The Flower), in which she literally replaces women's lifetime scars of domestic abuse with tattoos that are beautiful, empowering, and transformative. As she describes...

“They come to the studio, share their stories of pain and resilience, and they show me their scars. Embarrassed, they cry, and hug me … It is wonderful to see how their relationship with their bodies changes after they get the tattoos.”

Fostering Connection

Traumatic events stop time and leave us untethered from humanity. An important aspect of the healing potential of a tattoo—whether it memorializes a loved one, bears witness to survival, or shouts out a mission of change—is that it invites connection: to self, to others, and to the future.