Chronic Pain

Drinking to Ease Chronic Pain Ultimately Makes It Worse

A prescription for double trouble: how drinking alcohol fuels chronic pain.

Posted February 25, 2024 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- The link between alcohol consumption and chronic pain is complex and often reciprocal.

- It’s not uncommon for people dealing with the challenges of chronic pain to use alcohol to self-medicate.

- People with chronic pain drink to feel less uncomfortable but drinking ultimately increases their pain.

- New research reveals how alcohol use and withdrawal increase pain as well as hypersensitivity to pain.

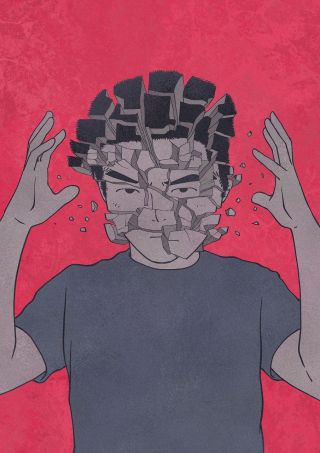

The link between alcohol consumption and chronic pain is complex. It's not unusual for people with chronic pain to consume alcohol to self-medicate—to drink to help sand down the sharp edges of their pain and turn down the volume of their discomfort. However, what starts out as something that seems like a solution often becomes part of the problem and can even make chronic pain worse.

In fact, chronic pain and alcohol consumption often combine to create a vicious circle wherein people with chronic pain drink to feel less uncomfortable, but drinking ultimately increases their pain. Pain is a widespread symptom in patients suffering from alcohol dependence and it’s also a reason why people are driven to drink more.

How drinking alcohol can exacerbate pain:

- Alcohol interferes with the circadian rhythm that governs our sleep cycle and inhibits REM (deep) sleep. As a result, people may fall asleep more easily after drinking, but they are more likely to experience less restful and interrupted sleep. Poor quality of sleep impairs the body’s ability to recharge, repair, and heal, which typically increases pain levels.

- Withdrawal from consistent alcohol use often increases pain sensitivity, which motivates most people to continue or increase their drinking to avoid or try to reverse withdrawal-related increases in pain.

- Over time, alcohol use actually generates pain in the form of small fiber peripheral neuropathy, the most common neurologic complication associated with alcohol use disorder.[1]

Recent research published in the British Journal of Pharmacology uncovered the specific pathways through which alcohol consumption and withdrawal can lead to increased pain as well as hypersensitivity to pain. The study by Scripps Research scientists used mice to identify potential targets for treating alcohol-associated chronic pain and hypersensitivity.[2]

According to this research, there are two different molecular mechanisms that appear to make people more sensitive to pain—one driven by alcohol intake and one by alcohol withdrawal. Three groups of adult mice were compared: those that were dependent on alcohol (representing excessive drinkers), those that had limited access to alcohol and were not considered dependent (representing moderate drinkers), and those that had never been given alcohol.

In the alcohol-dependent mice, allodynia (in which a harmless stimulus is perceived as painful) developed during alcohol withdrawal, and subsequent alcohol intake significantly decreased pain sensitivity. Separately, about half of the mice that were not dependent on alcohol also showed signs of increased pain sensitivity during withdrawal, but unlike the dependent mice, this pain was not reversed by re-exposure to alcohol.

When levels of inflammatory proteins were measured, the researchers discovered that while inflammation pathways were elevated in both dependent and non-dependent mice, specific molecules were only increased in dependent mice. This suggests that different molecular mechanisms may drive the two types of pain. It also indicates which inflammatory proteins may be useful as potential targets for intervention to combat alcohol-related pain. Follow-up studies are focused on how these molecules might be used to diagnose and more effectively treat alcohol-related chronic pain conditions.

In the meantime, while chronic pain should always be evaluated by a medical professional, there are many options for medication/opioid-based treatment, drawing on complementary and alternative approaches.

In addition to methods such as physical therapy, chiropractic treatment, and acupuncture, mindfulness practices, including meditation, help facilitate the ability to consciously observe pain sensations and the thoughts and emotions connected to them, be present with them, accept them, and make some peace with them rather than trying to medicate/numb or otherwise avoid them. This can significantly reduce the stress and suffering connected to chronic pain, which helps calm the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system and decrease pain perceptions.

Psychotherapy be extremely beneficial in dealing with chronic pain’s mental and emotional aspects. Because physical and emotional pain are related and activate one another, addressing depression, sadness, frustration, irritability, anger, anxiety, and fear has multi-level benefits. By shifting perspective and adjusting one’s thinking, it’s possible to change emotional responses and, in turn, dramatically decrease the level of suffering.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) are evidence-based approaches that incorporate mindfulness practices. ACT emphasizes building psychological flexibility and emphasizes values-congruent practices, while DBT emphasizes the development of emotional regulation and distress tolerance skills. These approaches transform our relationship with our thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations, including pain. This can change the quality of our experience in ways that change the subjective experience of pain as well as the suffering precipitated by it.

Copyright 2024 Dan Mager, MSW

To find a therapist near you, visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

[2] Vittoria Borgonetti, Amanda J. Roberts, Michal Bajo, Nicoletta Galeotti and Marisa Roberto, “Chronic alcohol induced mechanical allodynia by promoting neuroinflammation: a mouse model of alcohol-evoked neuropathic pain,” British Journal of Pharmacology. April 12, 2023. DOI: 10.1111/bph.16091