Sport and Competition

The Olympic Pressure to Repeatedly Win

When losing is really winning, and when winning becomes losing.

Posted July 30, 2021 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Key points

- How sporting success influences future athletic performance remains controversial; there appears to be huge variability amongst sports stars

- Success can end up being a burden if it's not handled correctly psychologically

- What you focus on during your performance appears to be hugely influential in determining your results

- Paradoxically don't focus on outcome or results, instead focus on the process; meaning focus on hitting the ball well, rather than consequences

The names of the gold, silver and bronze medallists dominate the headlines as elite sporting success is celebrated across the world… no one knows, or seems to care, who came fourth.

In sports, 4th place is surely the very worse position of all to finish in.

Yet now new research, examining the future career trajectories of Olympic athletes, suggests, somewhat astonishingly, that when it comes to your sporting destiny, 4th place is just as good as 3rd.

There are some profound implications, including the suggestion that sometimes winning, often for psychological reasons, can become a handicap, while losing can motivate some to future success.

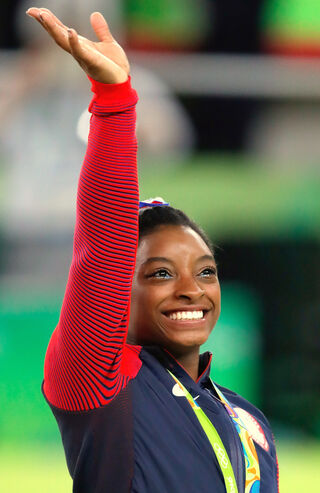

Four-time gold medallist Simone Biles has pulled out of some of the gymnast competition at the Tokyo Olympics, explaining that she needed to prioritise her mental health, but now this new research suggests a possible alternative explanation, linked to the expectations of past success producing a burden that can sometimes handicap future performance.

Richard Gong analyzed Olympic performance from the games in Athens 1896 to PyeongChang 2018.Gong is a pre-doctoral fellow at Yale University and formerly at University of California at Berkeley, where he published the paper entitled, ‘4th Place Finishers and Bronze Medalists: Differences in Olympic Career Outcomes.'

The analysis of 275,808 results across 132,283 athletes, found that a debut athlete who just misses out on a medal, performs as well in the future as the athlete right ahead of him or her, who wins a medal.

This is a surprising result because surely making it to the podium should predict better future performance for a variety of reasons.

For example, argues the author of the study, medals lead to much greater recognition and monetary rewards.

The United States, China, and India even pay athletes prize money for winning medals.

For PyeongChang 2018, according to a report quoted by Richard Gong, U.S. Olympian’s earned $37,500 for each gold, $22,500 for each silver, and $15,000 for each bronze.

These financial benefits, in addition to sponsorship opportunities that arise with greater recognition, can assist competing at the elite level. In the lead up to Rio 2016, Richard Gong quotes a report that more than 100 US athletes started ‘GoFundMe’ web pages, while some even applied for food stamps.

In which case the expectation would be that winning a bronze medal should predict better performance in the future for all sorts of reasons, compared to those who finish outside the medal table.

However, another possible factor, explains Richard Gong is that there may be negative consequences to Olympic success as well.

This may be particularly relevant to the Simone Biles story.

The study quotes how Olympic champion swimmers Michael Phelps and Ian Thorpe explained that expectations to win future medals can be both damaging to mental health and athlete performance.

Another study of 17 world champions, it was found that athletes could be divided into three groups based upon the consistency of their world class performance.

Kathy Kreiner-Phillips and Terry Orlick then at the University of Ottawa, uncovered the finding in their research entitled, ‘Winning After Winning: The Psychology Of Ongoing Excellence’.

Group 1, referred to as the ‘Continued-Success’ Group, continued to triumph after reaching the pinnacle in their sport.

Group 2, the ‘Decline-and-Come-Back’ Group, experienced a performance deterioration immediately following their first major win and took over a year to reach the top again.

Group 3, the ‘Unable-to-Repeat’ Group, only won big once during their career and were not able to repeat their successful world-class performance.

The study found one key difference between the groups was the focus of athletes.

In the ‘Decline-and-Come-Back’ Group and the ‘Unable-to-Repeat’ Group, (none of whom won their next competitions) the focus became very much oriented towards results, rather than the process of performing.

Twenty-one percent of these athletes said that they were focused on the outcome instead of connecting to their performance, twenty-one percent were focused on their own high expectations or others' expectations for them to win again. Twenty-one percent felt they were just not as clear minded in future competition, and 11% felt they tried too hard and consequently performed worse.

Kathy Kreiner-Phillips and Terry Orlick quote one athlete who captured this key point about how handling expectations after success becomes vital in predicting future success:

‘Living up to others' expectations was one of the harder demands. I think the ones who become and remain champions are the ones who live up to their own expectations and not to others', what's important to them and not to everybody else’.

If success can be a handicap this might explain Richard Gong’s finding that despite missing out on a debut medal, 4th place finishers in the Olympics perform no worse than 3rd place winners in subsequent Olympic Games, despite the fact finishing third is thought to be much, much better than finishing fourth.

Richard Gong argues that another possibility is that 4th place finishers, aware of how close they came to winning a medal, may be less content and more motivated to improve than 3rd place finishers.

An Olympic medal is in a strong sense a statement about the present and the past. It is testament to an extended period of training and sacrifice in the past, leading to outstanding performance on the day, in the moment of high stakes competition.

But do these medals predict destiny?

Does psychological research know what the future holds for those beaming faces on our TV screens reveling in their current success as they wave their medals at the cameras?

If fourth is just as good as third, then the issue is not just what medal you get, but how you react to it emotionally, and, sometimes, winning can end up causing you lose, just as losing can sometimes, help you eventually win.

References

Gong, Richard, 4th Place Finishers and Bronze Medalists: Differences in Olympic Career Outcomes (January 6, 2021). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3761403 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3761403

Winning After Winning: The Psychology of Ongoing Excellence. Source: Sport Psychologist . Mar1993, Vol. 7 Issue 1, p31-48. 18p. Kreiner-Phillips, Kathy; Orlick, Terry