Autism

“Thoughts Are Not Feelings” Is Bad Psychological Advice

A Personal Perspective: Time to stop spreading unscientific mind-body dualism.

Posted October 1, 2022 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

If you have been in therapy before or have picked up a cognitive behavioral or dialectical therapy book, you have likely encountered the adage that “thoughts are not feelings.” The statement intends to help clients distinguish between their interpretation of a situation and the emotional reality of how that situation affected them. Take, for example, this passage from the Dialectical Behavioral Therapy Workbook for Bipolar Disorder by Sheri Van Dijk:

When I ask a person how she felt in a situation, she may respond by saying, 'I felt that I was being criticized' or 'I felt that he should have understood how I was feeling.'

If you look closely, she didn’t actually describe an emotion, but stated what she was thinking about the situation.

Van Dijk explains that this patient feels angry or disappointed by past treatment. But as Van Dijk acknowledges, our emotions shape how we perceive the world. Conversely, the content of our thoughts impacts our emotions. When we dwell on unhappy subjects, we make ourselves sadder. The relationship between affect and cognition is a two-way street that never shuts down. So why do we even bother trying to cleave thinking from feeling in the first place?

“Thoughts are not feelings” is something patients who heavily intellectualize their emotions tend to hear from their therapists. Take, for example, this exchange I had with a therapist many years ago:

Me: Yet another friend of mine is struggling with suicide ideation and depression.

Therapist: And how do you feel about that?

Me: It feels like there is nothing I can do to protect people or to help people get better.

Therapist: That’s a thought, not a feeling.

If my therapist’s goal was to help me connect with my emotions, she could not have done a worse job. Rather than hearing my anguish, she disapprovingly corrected me. This made me trust her less and made me feel that how I emote was somehow “wrong” in her view.

When therapists chide patients to share a feeling and not a thought, they are typically requesting the patient provide a straightforward affect word such as “joyful,” “irate,” “disappointed,” “bashful,” or “sad.”

However, at that appointment, I did not feel emotion words such as “sad” or “guilty” did justice to the enormity of what I was going through. I was alarmed and had been for weeks, and I literally could not stop thinking about it. My thinking was clearly quite subjective, flowery, and intuitive: It was emotional. Yet my therapist shut me down for conveying feelings by sharing my thoughts.

Unfortunately, this approach may be common to a variety of therapeutic approaches. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) teaches patients to avoid cognitive distortions by identifying whether their thoughts align with reality. Dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) also involves instructing clients to draw a firm line between their thoughts and emotions. Returning to the Dialectical Behavioral Therapy Workbook for Bipolar Disorder, it tells the reader that a statement such as “I’m an idiot!” is a thought, not a feeling. But is there a more emotionally charged thought than one that rejects your entire selfhood like that? It’s hard to imagine ever thinking of oneself as an ‘idiot’ and not simultaneously experiencing a flood of negative emotions.

To say that one feels ashamed and embarrassed is to lose specificity in this case. “I’m an idiot!” (or “I feel like an idiot”) conveys that a person is experiencing profound negative emotions directed toward themselves and that those negative emotions connect with concerns about intelligence and capability. That says a lot about why the client is upset. Why would a therapist ever want to replace such a rich, contextual discussion with vague faffing to feelings?

In my book, Unmasking Autism, I describe how the social pressure to mask as neurotypical leads to many Autistic people being quite bad at knowing how we feel–especially in the heat of the moment. Scientists often call this alexithymia, and it manifests in many ways.

Autistic writer and researcher Stevie Lang observed that during sexual encounters, Autistic folks can’t always tell if we have genuinely consented to an activity or if we merely want to do something to please a partner. One Autistic person I interviewed told me she needs days to reflect on an experience before she can tell how it made her feel.

I am often the same way. Big losses and surprises throw me for a loop and leave me numb. “I’ll think about this and get back to you” is a life-saving phrase in such cases. It’s the way so many other Autistic people and I work. Thinking is part of how we arrive at how we feel. So for a therapist to tell us that all this crucial interior work is invalid because “thoughts are not feelings” is devastating.

This statement compounds the many other invalidating experiences Autistics have in a standard therapy office, such as being told our emotions look too “flat” or that we explain experiences in too much detail.

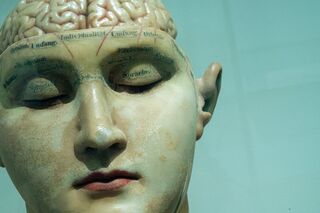

Thoughts are feelings. And feelings are thoughts. Just as behavior is communication. Many decades ago, psychologists did away with the concept of Cartesian Dualism, which looked at the mind and body as separate entities.

We know today that the mind and the body are one inseparable whole. Our gut biome affects how we feel. Our beliefs about food can alter our metabolism. Our facial expressions can shift our moods. Everything’s connected. And so, as psychologists, we must stop spreading the notion that we can draw a sharp dividing line between feelings and thoughts.