Sensation-Seeking

Why Would a Serial Killer Appear on a Game Show?

Games of chance sometimes attract risk-taking offenders.

Posted February 8, 2021 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Serial killers who crave publicity are drawn to the medium of television. Some send communications to station personnel, some appear on talk shows or documentaries, and a few play games. Literally.

In the news recently, we’ve seen articles about a murderer in Wales, John Cooper, whose participation on a game show in 1989 helped to confirm this “super burglar” as a serial killer. His crimes were dramatized in a three-part series, The Pembrokeshire Murders, and described in a crime documentary, The Pembrokeshire Murders: Catching the Game Show Killer.

Cooper liked games. In one called Spot the Ball, he won a car and 90,000 pounds. He quit his job and gambled his winnings away. In 1983, needing money, he took up the high-risk crime of home-invasion burglary. During one incident in 1985, he killed siblings, Helen and Richard Thomas, possibly because they’d caught him. He eliminated them as witnesses before setting fire to their house. Afterward, police discovered that both victims had been shot. Helen, with a rope around her neck, had also been sexually assaulted.

Although Cooper was a suspect, his family provided an alibi, and he avoided the police radar. He continued to break into homes. In 1989, Cooper appeared on Bullseye, a game show that paired amateur darts players with a quizzer. Cooper failed miserably at both throwing darts and answering questions about general knowledge. Yet he bragged about his detailed knowledge of the Pembrokeshire coastline. This would come to haunt him.

Three weeks later, Gwenda and Peter Dixon were killed in this area as they walked on a trail near their campsite. Their killer tied them up and forced them to reveal their bank card information. He then shot Peter three times and Gwenda twice. It appeared that she was also sexually assaulted and her shorts were missing. Cooper used their bank cards in multiple locations but still managed to elude the police. All they got were witness reports of a man with shaggy hair. Like the Thomas case from four years earlier, this double homicide went cold.

A decade later, Cooper was arrested for robbery and burglary. Among the evidence exhibits was footage of him on Bullseye, which showed his close resemblance to the witness reports of a bushy-haired man near the Dixon crime scene. In 2009, Cooper’s shotgun was linked to the murders, and also to several sexual assaults from 1996. A pair of shorts in his possession bore incriminating DNA. Cooper’s risk-taking ventures had finally shifted the odds against him.

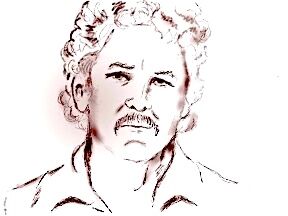

Similarly, Rodney Alcala, the “Dating Game Killer,” appeared on a 1978 episode of the TV show, The Dating Game. At the time, he’d already committed several sexual assaults and homicides and been placed on the FBI’s Most Wanted list. A member of the casting team didn’t like Alcala's audition, but his wife said Alcala would be popular with female viewers. He got on the show.

Cheryl Bradshaw, the bachelorette, questioned the three eligible bachelors who sat on stools on the other side of a partition. Alcala answered most of her questions with playful sexual innuendo. He made her laugh, and she picked him for the date. However, once she met him, she found him creepy. She declined to go on the date.

Alcala was eventually convicted of seven murders, and he’s been charged with one more. During his trial, in which he defended himself, he showed that clip of The Dating Game to try to discredit a key piece of evidence. It didn’t work. He lost.

Although not game shows, other notable TV offender appearances include Stephen Port, a British killer of four gay men in East London. He appeared in 2015 on an episode of Celebrity Masterchef, helping a singer and an actress make pasta and meatballs. By then, he’d killed his first victim. In Vienna, Austria, Jack Unterweger played a game of chance by using his celebrity status to deflect suspicion as he killed nearly a dozen women. Influential writers and critics had helped to secure the convicted murderer’s release from prison because he'd shown writing talent. He embraced the spotlight and used his visibility to taunt police with their failure to catch the “the Vienna Courier.” Him. Yet his hubris, combined with his repetitive MO, turned his own game against him.

Killers who play the odds sometimes learn that the odds will actually play them.