Psychology

In-Vivo Mere Exposure Effect Manipulation: A Social Dilemma

Facebook ads have much more power than you think.

Posted April 1, 2019

The controversy over foreign influence into the 2016 election involved a debate over whether or not targeted facebook advertising courtesy of Cambridge Analytica and Facebook was more than just an attempt at influencing the election. Was it actually effective in doing so?

Beyond the presence of mere meddling: Evaluating the impact of foreign influence via targeted social media ads on the 2016 election

Since Mueller released his indictment against the Internet Research Agency (USA v. Internet Research Agency, LLC et al, 02/2018) which described the extent of foreign social media interference in the 2016 election, the mainstream media, such as MSNBC and CNN, regularly highlighted the meddling-effectiveness debate. More recent revelations have exposed the collaborative efforts of Facebook and Cambridge Analytica to target users with political ads based on their “psychographic profile” (think every socio-demographic, psychometric, or personality variable possibly scrapped from Facebook using AI, data science, and computer science, etc).

Last week, the interference-impact (meddling-effectiveness) question was emphasized during the testimony of the past ambassador to Russia, Michael McFaul in front of the House of Representatives Oversight Intelligence Committee on March 28th, 2019, broadcast on C-SPAN. Importantly and correctly, McFaul asserted that it would not be possible to assess the unique impact of targeted FB ads on the 2016 electoral outcome independent of all of the other variables that would likely impact voter behavior. In this blog post, I offer an alternate perspective that permits stronger conclusions to be drawn about the impact of the “meddling.”

Meddling? Yes! Did it work? See below.

One promising approach to address this question is to conceptualize Facebook ads as the mere exposure of an emotional stimulus to specific users in an effort to persuade people to vote in one way or the other. What do psychologists know about the effects of merely exposing an individual to a stimulus, typically a visual stimulus? Quite a bit. The famous social psychologist, Zajonc, was one of the major figures to study what has been labeled "the mere exposure effect." The mere exposure effect refers to the finding that individuals prefer stimuli that they have previously been exposed to, even if only for milliseconds or below the threshold for conscious processing. Perhaps, the explosion of research and funding for psychologists to study the mere exposure effect for at least the past four decades has been related to a recognition of the important implications this research has for marketing, advertising, and political campaigns. However, the reasons for considerable long-term government funding and extant research interest in the mere exposure effect is beyond the current scope.

What does mere exposure have to do with Facebook ads?

Practically by definition, an ad involves the mere exposure of a visual image that expresses an idea, trope, schema, or meme, sometimes involving text. Sometimes there is no text. Sometimes ads are videos. Regardless of the specific form, an ad exposes a person to an idea e.g., "politician X is strong," "politician Y is corrupt," or "vaccinations are bad" etc.

Accordingly, the mere exposure effect is inextricably linked to the psychology of marketing on Facebook and elsewhere.

Applied Psychology: Issues of External Validity

In academic psychology research, often in laboratory settings using college students as participants, critics have emphasized that the results of laboratory studies on college students tell us little about the average adult in the general population in the real world. External validity refers to the extent to which the results of a study can be generalized to the real-world. It turns out that college student samples generally do pretty well in generalizing to the general population. Highly controlled, experimental cognitive as well as emotion and psychophysiology laboratory studies are arguably very valuable in the context of generalizability. The argument, which I find very compelling, is that if a statistically significant effect is found in a psychology experiment, then—given all of the controls and an artificial and lab setting—it is logical to infer that the effects of variables under study in the lab will have much larger effects in the real world because of the absence of experimental control.

External validity of the mere exposure effect: Marketing implications

In academic psychology, research on the mere exposure effect has a long history that is beyond the scope of a single peer-reviewed journal article let alone a psychology today blog post. Nonetheless, an overview of some of the major findings and experimental designs is warranted. Zajonc (1968) reviewed the data on word frequency and positivity ratings for those words and reported that the frequency of a word (an index of exposure) had a significant effect on liking ratings of those words, with effect sizes ranging from 0.38 to 0.63. Zajonc (1968) found that participants rated words as more positive if they had previously been exposed to those words as, even after controlling for lexical characteristics that could influence liking ratings. Bornstein & D’Agostino (1992) found that even the subliminal exposure of ambiguous geometric stimuli had significant effects: participants rated shapes that they were previously exposed to implicitly (i.e., without their conscious awareness) as more positive than shapes they had not been previously exposed to.

In a recent meta-analysis of studies on the mere-exposure effect, Montoya et al. (2017) reviewed numerous studies examining the effects of merely exposing different stimuli to participants for different durations, different numbers of repeated exposures, and different as it was found that the repeated mere exposure of a stimulus increased liking of that stimulus in a manner that co-varied with the number of exposures, such that more exposures was linked with greater liking of the stimulus as compared with one or fewer exposures. (Interestingly, a curvilinear relationship was found between the number of exposures and liking, such that after a point, repeated mere exposure no longer co-varies with increased liking but flattens out or slightly decreases.) Affect sizes for the mere-exposure effect in this recent meta-analysis fell within the approximate range of 0.4 to 0.8, with some variation depending on the procedure and stimuli of the specific experiment. A rough estimate of the average effect size for the mere-exposure effect based on my understanding of the data in this meta-analysis is about 0.6.

How big is the mere-exposure effect? Effect sizes and implications for the effectiveness of foreign meddling.

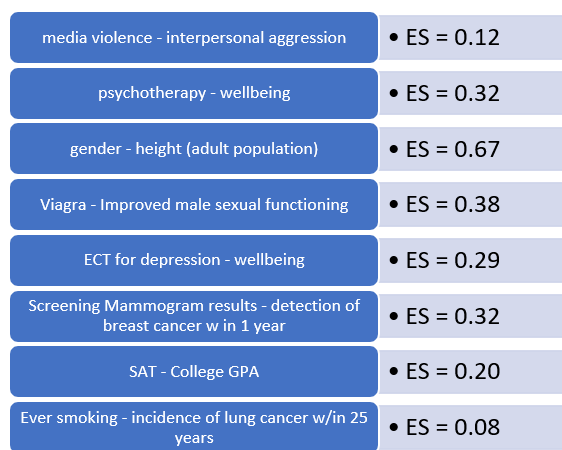

The mere-exposure effect is surprisingly robust and impactful. It really effects how much one likes a stimulus—and the idea, schema, meme, or trope that the stimulus represents—to a significant degree. Based on brief review of the literature on the mere-exposure effect, effect sizes range from .4 to .6 and above. This represents a very large effect in behavioral science. One way to make sense of effect sizes in psychology research is to examine the effect sizes between variables that we are familiar with. In a landmark article on psychological testing published in American Psychologist, the authors provide the effect sizes for common relationships between two variables (e.g., how large is the effect of smoking on lung cancer? How large is the effect of early attachment on later personality or attachment?) For example, see the table/image below for a look at the effect sizes representing the strength of the relationships among various pairs of variables.

By examining existing effect sizes, quantified by R (as is the case with the table above) Cohen’s D, or another coefficient; for familiar relationships, we are in a better position to evaluate the impact of Facebook targeted political ads since we know roughly the effect size of the mere exposure effect on liking (attitudes) for neutral or meaningless stimuli.

Effect size of an ambiguous or meaningless visual image on liking: implications for personally-relevant stimuli.

Consider a scientist who wants to compare the average height of adult males and females. Not surprisingly, the average height of males is higher than the average height of females with an effect size of roughly 0.6 (roughly equivalent to the size of the mere-exposure effect on liking of geometric stimuli, i.e., shapes, as well as linguistic stimuli, e.g., words).

To translate, the odds that mere exposure to a meaningless Facebook ad/visual image (e.g., that portrays a geometric shape) increases one’s liking of that image are roughly equivalent to the odds that if one were to select a female at random from the general population that she would be shorter than a male selected at random from the general population. Mere exposure to stimuli predicts subsequent liking of that stimulus to a degree that is roughly equal to or greater than the strength of the relationship between viagra and male sexual performance. How much would you be willing to wager that a male selected at random would be taller than a female selected at random? If you like odds, betting, and math, then you might want to go all in on this bet. You should also be willing to go all in on the bet that mere exposure to a neutral ad on Facebook will predict subsequent liking of that ad.

Generalizability and Real-World Applications

Based on a light review of the literature, it appears that the best estimate for the effect of mere exposure on liking is approximately (and conservatively) 0.4 to 0.6** for neutral or meaningless stimuli. This estimate likely substantially under-estimates the impact of repeatedly exposing individuals with specific “psychographic” profiles to stimuli that is not ambiguous nor meaningless. When stimuli are targeted to a specific psychographic profile, it is reasonable to expect the mere exposure effect size to increase considerably. Furthermore, three processes can be hypothesized to significantly increase the impact of mere or repeated exposure to a Facebook ad on the subsequent liking of that ad:

(1) Firstly, personality-based or other demographically variable based ad-targeting likely increases the effect of merely exposing an individual to a neutral or meaningless Facebook ad. Consider studies on the Emotion Stroop Effect. These studies have found that individuals display a slower latency to personally relevant, threat words as compared to neutral words, indicating a significant effect of exposing individuals to personally relevant stimuli.

(2) Secondly, during the 2016 campaign/election, Cambridge Analytica/Facebook were very careful to select stimuli (ads) that were not meaningless or neutral at all. The ads (visual stimuli) were loaded with personally relevant tropes designed to maximize the impact of exposure.

(3) Lastly, Facebook may repeatedly expose users to different ads that contain the same schema or idea or trope, thereby increasing liking for the relevant idea. Facebook may also repeatedly expose individuals to the same ad multiple times as well, thereby increasing the liking for that specific ad.

Conclusion

If the chances that foreign meddling (via Facebook-Cambridge Analytica targeted advertising) effected the outcome of the 2016 election are at least the same as the odds that a random male is taller than a random female, then there is a strong, empirically based rationale for concluding that meddling effected the outcome of the 2016 election. As they say on Twitter, Full Stop (almost).

Of course, the relationship between liking (attitude) a politician or idea and voting (behavior, action) is not a perfect 1:1 correspondence but extant empirical research in social psychology indicates a strong link between attitudes and behavior. Nonetheless, even taking into account this mitigating factor, I find the argument that it is impossible to know if meddling in the 2016 election had an effect or the claim that there was no effect to be dishonest, misleading, and inconsistent with decades of psychological science.

**Note effect size can be calculated using a variety of statistical coefficients, including Cohen’s D, Beta, Pearson R. At the risk of misinterpreting the relations among these estimates of effect size, I have treated them as roughly equivalent. The Meyer et al. (2001) effect sizes are reported with the coefficient, Pearson R.

Keywords: Cambridge Analytica, Facebook, Political Ad Targeting, Attitudes, and Voting Behavior

References

Bornsetin, R.F. & D'Agostino, P.R. (1992). Stimulus Recognition and The Mere Exposure Effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 63 (4).

House Select Intelligence Committee, Testimony of Michael McFaul, 03/28/2019, C-SPAN.

Meyer, G., Finn, S., & Eyde, L. et al. (2001). Psychological Testing and Psychological Assessment. American Psychologist. 56 (2).

Montoya, R.M., Horton, R.S., Vevea, J.L. et al. (2017). A Re-Examination of the Mere Exposure Effect: The Influence of Repeated Exposure on Recognition, Familiarity, and Liking. Psychological Bulletin. 143 (5).

Zajonc, R.B. (1968). Attitudinal Effects of Mere Exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Monograph Supplement. 9 (2).