Creativity

Time Pressure and the Trying Trajectory of Team Creativity

Why the midpoint of project timelines is a critical window for breakthroughs.

Posted May 10, 2021 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Too much time can be just as detrimental to a project as too little.

- The midpoint on a project timeline often marks a turning point for team creativity and productivity.

- Understanding the psychological effects that time can have on a project can help teams maximize their resources.

We've all probably been there at least once, and perhaps more times than we care to remember. The group or team project that, from the outset, just seems to be going nowhere. There's lots of animated discussion, many meetings or emails, plenty of back-and-forths (and back again) with ideas and possibilities. New options and variations on options keep appearing. It can all seem so meandering, so directionless, even counterproductive...

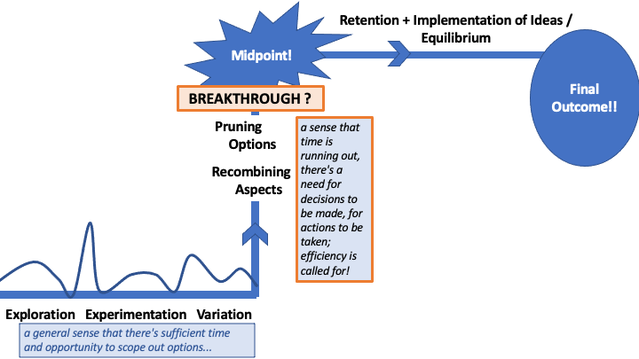

But then, as the deadline for the project approaches and the team draws nearer to the midpoint of the timeline, things start to happen. There's a flurry of decisions; some possibilities are dropped or unceremoniously jettisoned as unfeasible or too vague; other possibilities are merged or recombined into promising, specific, and welcomed ones. The team assigns portions of the project to smaller subgroups, and the subgroups or individuals within them start working in earnest and in parallel. There's a newly emerging collective feeling of purposeful forward endeavor and growing optimism that the team will successfully make or deliver the desired outcome.

But why does the creative process of team projects, and often of individual projects too, follow this seemingly strange and decidedly bumpy trajectory across time?

Time as a resource and a constraint: Neither too much nor too little

Time is undoubtedly a valuable and necessary resource for creative endeavors. It is also very often a limited resource that is felt to be in short supply. In in-depth interviews with more than 25 research and development (R&D) teams, with goals ranging from developing new electronics technology to software innovation to novel materials for the medical industry, constraints on time were by far the most frequently mentioned constraint on teams' creative processes.

Yet, perhaps surprisingly, having a very large or unlimited amount of time is not necessarily a boon to creative ideation or innovation. Instead, several theories suggest that the amount of time that is dedicated to a project, like other resources, can be too generous; there can be too much time allotted. If so, the overly expansive time allocation can paradoxically produce a sense of complacency and insufficient attention to whether the time is being spent wisely.

Creative and innovative thinking clearly requires enough room for flexibility, experimentation, and exploration—or what has been termed "slack" by organizational researchers. Yet too much room, or too much slack, can smother rather than spark imagination and ingenuity.

Researchers have found that the midpoint in a project timeline often seems to be a dividing line—a psychological breaking point or inflection point—between two contrasting team perspectives on time. Before the midpoint, teams may have a sense that there's a sufficiently generous amount of time remaining, allowing them to engage in wider exploration, experimentation, and varied responses. But once the midpoint of the timeline is reached or is closely approaching, there's often a turning point.

Now, teams start to feel anxious that it's a time for decisions to be made, for actions to be taken. They are on the lookout for increased efficiency in how effort—and time—are spent. At this point, there may be a valuable pruning of ideas and/or synergistic merging and ingenious recombining of ideas: The team zooms in and selects the smaller subset of ideas that the project will commit to carrying forward.

The qualitative forms of time

The creative and innovative knowledge outcomes of time given to creative projects and innovation are not just a matter of "how much" time (the quantity of time) that is devoted. The quality of time also matters. It is crucially important how the allotted time subjectively feels to the team or individual, and how the allotted time connects to the required deliverables, including the final deadline of the project.

Indeed, innovation researchers are increasingly focusing on the many ways in which project time is not simply "time" but comes in many different forms. And the different forms of time relate not only to a central creative aim but also to "off-shoot" (tangential, branching) creative ideas that happen to emerge. For these tangential, branching ideas, too, there needs to be sufficient time after idea generation for exploration, experimentation, and variation. Without the right amount of such "slack," potentially valuable ideas will never be given the space and opportunity to fully develop. We and our teams need to be mindful of the different psychological qualities of time and their dynamically changing—sometimes bumpy—contributions to the creative process.

References

April, S., Oliver, A. L., & Kalish, Y. (2019). Organizational creativity‐innovation process and breakthrough under time constraints: Mid‐point transformation. Creativity and Innovation Management, 28, 318–328.

Nohria, N., & Gulati, R. (1996). Is slack good or bad for innovation? Academy of Management Journal, 39, 1245–1264.

Puech, L., & Durand, T. (2017). Classification of time spent in the intrapreneurial process. Creativity and Innovation Management, 26, 142–151.

Richtnér, A., & Åhlström, P. (2010). Organizational slack and knowledge creation in product development projects: The role of project deliverables. Creativity and Innovation Management, 19, 428–437.

Russo, B. D. (2014). Creativity and constraints: Exploring the role of constraints in the creative processes of research and development teams. Organization Studies, 35, 551–585.