Fear

The Monsters That Make Us: Things That Go Bump in the Mind

A brief history of some things that scare us.

Posted March 8, 2018 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

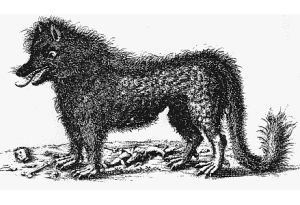

Monster comes from the Latin monstrum, meaning something unnatural or unpleasant. Early thinkers thought a monster was some malfunction of nature. There are plenty of monsters in classical mythology. For example, Cerberus is a three-headed dog with a serpent for a tail. Called “the hound of Hades,” Cerberus guards the gates of the underworld to keep the dead from leaving. A serpentine water monster, the multi-headed hydra poses a unique problem as it regenerates two (or more heads) for every head severed making it difficult to kill. Medusa, a gorgon, has wings and venomous snakes in place of hair. Looking at her directly turns the viewer to stone.

Of course, monsters are not found only in times past; we can find plenty of them in the modern era as well. Frankenstein’s Monster or the Creature comes from Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus written in 1818 by Mary Shelley. The novel details Victor Frankenstein’s assembling and animation of a person from various body parts of deceased persons. King Kong, the gigantic ape, first appears in the 1933 movie of the same name. In 1954 Godzilla debuts as an enormous prehistoric sea monster.

There are also friendly monsters such as the Assyrian lumasi (singular lamassu), protective deities with a human head, the body of a bull or a lion, and bird’s wings that originate from the ancient Mesopotamian religion. Moving to the twentieth century we find Chewbacca, the tall, shaggy Wookie from Stars Wars (modeled on director George Lucas’ dog), Cookie Monster from Sesame Street, and the Iron Giant from the 1999 film of the same name.

While the softer monsters may delight us, the scarier monsters are the ones we should pay more attention to. They are the embodiments of our fears, concerns, and anxieties, urgent messengers from the depths of the mind. In fact, Sigmund Freud argued that the monsters in our dreams are created by our unconscious mind and reflect our current worries and fears—even those we fail to consciously acknowledge. Returning to classical myth, the three heads of the Cerberus are symbols. Some think the heads symbolize three kinds of human hatred, three kinds of human greed, or the three stages of the human life cycle. The hydra with its multiplying heads represents futile attempts to solve a problem that results, ironically, in increasing it exponentially. Medusa demonstrates the difficulty, perhaps even fatality, of directly confronting and addressing a problem that one is not yet prepared or equipped to process.

Moving forward to the modern, many of our monsters point to an unsure relationship with technology, nature, and/or science. Frankenstein’s Monster is an allegory for experimenting with unknown sciences and forces, creating something with the capacity for killing, and being unable to stop or recall it. It is not a coincidence that Shelley gave the novel the subtitle The Modern Prometheus. Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to humanity. In this same sense, Victor Frankenstein steals the spark of life reserved for the sacred realm and brings it to the realm of the profane. It was an unnatural creation of life that had a monstrous result. Such an act violates a basic contract with the universe and brings up questions in areas such as medicine, resuscitation, brain/body death, and the right to die. Although scientists today have codes of conduct in regards to the experiments they conduct, many still fear there is a cost to pursuing certain types of knowledge. Similarly, King Kong taps into longstanding fears of being overwhelmed by the natural world and the various creatures within—The Planet of the Apes series delves into a lot of this subject matter, too. Psychologists worry that with our increased dependence on technology and a decrease in the amount of time we spend outdoors our fears of the natural world will only increase.

Godzilla takes it a step further by adding a nuclear element. First appearing in 1954’s Godzilla, Godzilla is awakened and strengthened by nuclear power. Considering that the film is Japanese and that the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki occurred less than a decade before Godzilla’s debut, the connections between nuclear force and Godzilla are clear. Other mythological sea beasts have connections to modern technologies. The kraken is a legendary sea monster, akin to a giant squid. For early sailors, it was probably an exaggeration of something they actually saw or heard of. However, the kraken has also come to symbolize a huge, unseen force waiting beneath the surface to erupt, much like a nuclear weapon, and devastate us. Consider these lines of description from Lord Alfred Tennyson’s “The Kraken.” He “will lie / until the latter fire shall heat the deep / Then once by man and angels to be seen, / In roaring he shall rise and on the surface die.” Though it was written in 1830 and so Tennyson most likely was not thinking specifically of nuclear force, the poem sounds eerily like a narrative of a nuclear weapon waiting in a silo to be launched and lay waste to the world.

Monsters frighten us—whether they are the monsters from nature or the monsters we have created. Nonetheless, we must not look away because the most effective way to deal with a monster is to confront it. Another root word contained within monster is the Latin monstrare meaning to show or demonstrate. Monsters are trying to show us something important. Monsters are masks for what we really fear.