Health

Immune Health and Mental Illness

What's the gut got to do with it?

Posted July 18, 2022 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- The gut is home to 70-80% of the body's immune cells.

- The enteric nervous system in the gut contains more than 100 million neurons.

- Alterations in the gut microbial environment result in a proinflammatory immune response.

- Systemic inflammation can lead to neuroinflammation, mood disorders, and neurodegenerative disease.

The Playground

The digestive tract, or alimentary canal, is separated from the body’s internal systems by means of a semipermeable mucosal layer surrounded by surface epithelial cells. The tight junctions between the gastrointestinal tract cells function as the gateway for nutrients as well as healthful byproducts of the trillions of friendly microbes residing in the intestines (the gut microbiota). Because it is exposed to all ingested foods as well as resident and potentially pathogenic microbes, and is in direct contact with the enteric nervous system, the intestinal barrier plays a critical role in balancing immune response and tolerance.

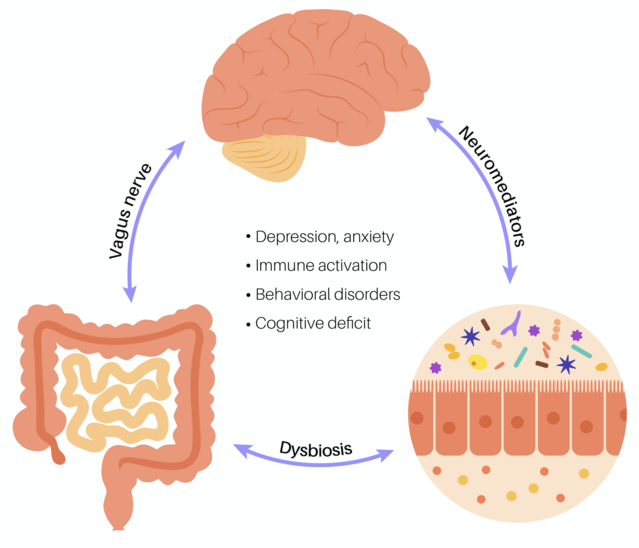

The interaction between the gut microbes, the body’s immune system, and the central nervous system plays an important role in mental health. The relationship between these three systems is a continuous and complex dance, and there are a few proactive measures that can be taken to help keep the system running smoothly.

The Players

The GALT

The gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) is considered the largest immune organ in the human body. A component of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), the GALT is comprised of many different types of immune cells and is responsible for auditing food antigens and bacteria as well as helping to regulate the intestinal immune response.1

The ENS

The enteric nervous system (ENS) is part of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which is responsible for automatic bodily functions such as breathing, heart rate, and digestion. It is sometimes referred to as the “second brain,” as it contains over 100,000 nerve endings and more than 100 million neurons.2

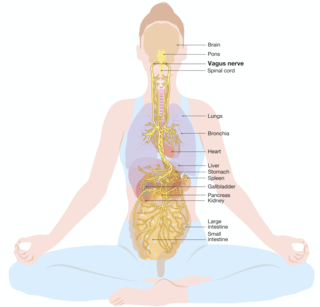

The neurons of the gut control gastrointestinal motor functions and secretion of gastrointestinal enzymes, while communicating with the brain through vagus nerve signals and neurotransmitters. In fact, it is estimated that up to 95% of the body’s "feel good" serotonin is produced in the gut.3 The components of the so-called gut-brain axis include the enteric nervous system, the sympathetic nervous system, and the hypothalamic-pituitary (HPA) axis.

The CNS

The brain is a primary component of the central nervous system (CNS). The brain and the intestines are in constant communication through the vagus nerve, the spinal cord, and the sympathetic system of the ANS, responsible for the fight-flight-or-freeze response.4

The Gut Microbiota

Once thought to outnumber human cells, the total number of microbial cells in and on the body are approximately equivalent to the number of host cells5, with the largest community located in the gut. Through a variety of mechanisms, trillions of these microorganisms stimulate and regulate the intestinal epithelial barrier, the enteric immune system, and the intestinal immune cells. These organisms also produce molecules that influence inflammatory response and neurotransmitter production.

When the System Breaks Down

Interactions of the gut-immune-brain axis occur on many complex levels, but here we will outline a common pathway through which an imbalance in the gut microbiome and its impact on the immune system can result in central nervous system damage and mental health symptoms:

- Gut dysbiosis, or alteration to a healthy gut microbiome, resulting from things like a poor diet and/or disease processes, can lead to intestinal barrier hyperpermeability, or "leaky gut."

- Leaky gut allows toxins and pathogens to leak out of the digestive tract and into the body, triggering an immune response from the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) 6..

- Secretions of triggered immune cells, such as cytokines, can result in a defensive response leading to chronic systemic inflammation.7

- Systemic inflammation has the ability to degrade the protective blood-brain barrier.

- Immune cells responsible for maintaining balance in the central nervous system (microglia) are activated to a proinflammatory state by the circulating microbial toxins (lipopolysaccharides), resulting in neuroinflammation.7

- Neuroinflammation can lead to a variety of mood disorders and neurodegenerative diseases.7

Proactive Steps to Protect Gut, Immune, and Brain Health

Supporting healthy gut microbiota balance and function is a primary step in avoiding the destructive gut–immune-system–mental health cascade. Fortunately, for most individuals, the process is a relatively simple one:

1. Remove Food Allergens

Food allergies (IgE antibody-mediated) and sensitivities (IgG antibody-mediated) will initiate an undesired immune response, gastrointestinal damage, and potential blood-brain barrier damage, which compromises mental health. As such, known food triggers should always be removed from the diet. Elimination challenges (elimination of potential food allergens to assess changes in symptoms) and blood serum allergy testing are two of the best methods to identify allergies and sensitivities. Common culprits include dairy, soy, and gluten.

2. Feed the Good Gut Microbes

Eat whole foods rich in complex fibers such as whole grains and vegetables, which, while indigestible by humans, serve as a staple for healthy gut microbes. Quality prebiotic formulations can also supply such plant fibers and as a bonus help keep the digestive process working smoothly. Prebiotic fibers such as fructooligosaccharides (FOS) and galactooligosaccharides (GOS) have been found to play a role in alleviating depressive symptoms.

3. Heal and Balance the Gut

Common natural health supplements including L-glutamine, omega fatty acids, collagen, and others have been shown to help heal gut hyperpermeability. A quality probiotic formulation8—with a balance of strains proven to produce the short-chain fatty acids that can repair intestinal damage, help eliminate circulating toxins, and enhance neurotransmitter production—is a great way to boost a healthy microbial population.

Final Thoughts

The gut-immune-brain connection is highly integrated and constantly communicating, with most of the messages beginning in the gut. Disruptions in the gut microbiome can therefore wreak havoc in many forms—from the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)9 or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) to depression.10 Fortunately, simple gut-supportive measures can play an important role in maintaining system balance and overall mental wellness.

References

1. Wiertsema SP, van Bergenhenegouwen J, Garssen J, Knippels LMJ. The Interplay between the Gut Microbiome and the Immune System in the Context of Infectious Diseases throughout Life and the Role of Nutrition in Optimizing Treatment Strategies. Nutrients. 2021 Mar 9;13(3):886. doi: 10.3390/nu13030886. PMID: 33803407; PMCID: PMC8001875.

2. Yoo BB, Mazmanian SK. The Enteric Network: Interactions between the Immune and Nervous Systems of the Gut. Immunity. 2017 Jun 20;46(6):910-926. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.05.011. PMID: 28636959; PMCID: PMC5551410.

3. Strandwitz P. Neurotransmitter modulation by the gut microbiota. Brain Res. 2018 Aug 15;1693(Pt B):128-133. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.03.015. PMID: 29903615; PMCID: PMC6005194.

4.Giuffrè M, Moretti R, Campisciano G, da Silveira ABM, Monda VM, Comar M, Di Bella S, Antonello RM, Luzzati R, Crocè LS. You Talking to Me? Says the Enteric Nervous System (ENS) to the Microbe. How Intestinal Microbes Interact with the ENS. J Clin Med. 2020 Nov 18;9(11):3705. doi: 10.3390/jcm9113705. PMID: 33218203; PMCID: PMC7699249.

5. Ron Sender, Shai Fuchs, Ron Milo: Are We Really Vastly Outnumbered? Revisiting the Ratio of Bacterial to Host Cells in Humans, in: Cell 164, January 28, 2016

6. Uniyal, A., Tiwari, V., Rani, M. et al. Immune-microbiome interplay and its implications in neurodegenerative disorders. Metab Brain Dis 37, 17–37 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11011-021-00807-3

7. Wang J, Song Y, Chen Z, Leng SX. Connection between Systemic Inflammation and Neuroinflammation Underlies Neuroprotective Mechanism of Several Phytochemicals in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018 Oct 8;2018:1972714. doi: 10.1155/2018/1972714. PMID: 30402203; PMCID: PMC6196798.

8. Grumet L, Tromp Y, Stiegelbauer V. The Development of High-Quality Multispecies Probiotic Formulations: From Bench to Market. Nutrients. 2020 Aug 15;12(8):2453. doi: 10.3390/nu12082453. PMID: 32824147; PMCID: PMC7468868.

9. Moser, A.M., Spindelboeck, W., Halwachs, B. et al. Effects of an oral synbiotic on the gastrointestinal immune system and microbiota in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Nutr 58, 2767–2778 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-018-1826-7

10. Moloney RD, Johnson AC, O'Mahony SM, Dinan TG, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B, Cryan JF. Stress and the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Visceral Pain: Relevance to Irritable Bowel Syndrome. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2016 Feb;22(2):102-17. doi: 10.1111/cns.12490. Epub 2015 Dec 10. PMID: 26662472; PMCID: PMC6492884.