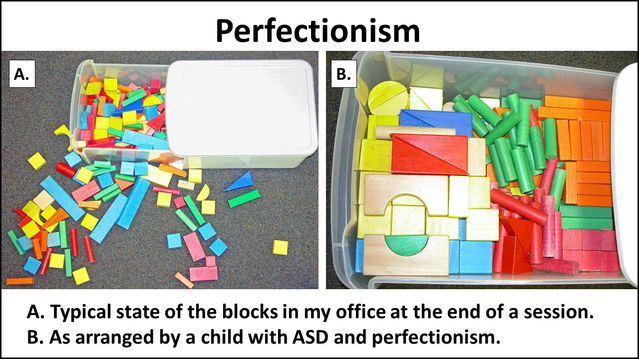

Perfectionism

The 8-Ball from Hell of ASD: Perfectionism

How to draw the line between healthy striving and self-destructive behavior.

Posted September 7, 2016

Attention to detail, and doing things the right way are both admirable traits, but as my stepmother was fond of saying, “Too much of a good thing is no good.” There is an invisible threshold between pursuit of excellence (a “good thing”) and dysfunctional perfectionism (not so good). Speaking personally, that threshold is determined not only (or even primarily) by the level of effort we put into a task, but by the backlash of self-criticism that comes if we don’t meet our own self-appointed (and impossibly high) standards.

I learned from one of my daughters to use the phrase “Trial and correct,” rather than “Trial and error.” It makes a big difference. A star athlete, virtuoso musician or ballerina will practice for years until they have achieved near-perfection; but they don’t berate themselves for falling short. They will analyze their performance, and try to do better the next time, but underneath all that hard work, their attitude is “I will do my best. That’s all anyone has a right to expect of me, and that’s all I have a right to expect of myself.” The perfectionist, on the other hand, will beat up on him/herself for not getting things exactly right – whether it’s a broad jump, a math problem, or cleaning the kitchen floor. Ask me how I know this! And I have seen this same process play out over and over again in my patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Here are a few vignettes, all of which illustrate variations on the theme of perfectionism (names and details have been changed to preserve confidentiality):

A classroom teacher wrote about one of my patients (a 7-year-old boy with high functioning autism, anxiety, and perfectionism): “Tony tries to exclude himself from any ‘competition’ types of games or activities, as he really dislikes being ‘wrong,’ ‘out,’ or to lose. On the times he has had tantrums after being ‘out’ or when his team has lost, the other children have been very empathetic towards him and he has not lashed out at them. His frustration appears to be with himself.” At Tony’s next office visit, I tried to engage him on the subject: “Sometimes you just need to do your best, and then move on,” I said in an encouraging tone of voice, then asked him “What do you think of that?” “Not much,” he replied bluntly.

-----------------------------------

Sam, a 12-year-old with superior IQ, autism and perfectionism earnestly attempted the Bender-Gestalt figures (a shape-copying task), but became overwhelmed, repeatedly erasing and re-erasing. He went so far as to measure the distance between the dots on one of the stimulus cards with his finger, trying to replicate the spacing exactly. “If I can’t get something right I get angry with myself… Sometimes I take it out on other people,” he confided. As he labored mightily over the cards, he sighed “This is torture…” After he had manfully struggled over a single card for several minutes, we opted to move on to another task.

-----------------------------------

Billy, a boy with ASD and normal nonverbal IQ, whom I diagnosed on the spectrum at age 3, came in at age 8 with a recent history of severe tantrums at school. A behaviorist had done a functional behavioral assessment (“FBA”) and was puzzled: Billy was not being permitted to escape from task, nor was he getting additional attention or gaining access to desired activities (“escape,” “attention,” and “access” are the 3 “functions” that behaviorists commonly look for when analyzing disruptive behavior). The school personnel were stumped. Why was Billy having tantrums? The only clue was that the outbursts always occurred at transition times. The simple answer would have been “Well of course. People with autism don’t like transitions.” But why didn’t Billy like transitions? (“Just because” is not a good enough answer.) Fortunately, Billy was very verbal, and Billy and I were on friendly terms from previous visits. “Billy,” I asked in a caring, but light-hearted tone of voice, “You’re always getting in trouble at school. What’s going on?” And Billy replied, in his earnest monotone: “I’m afraid that if I hand in my work, I’ll never get a chance to go back and make it perfect.” (Amazing what you can learn by asking the child, isn't it?) So the solution was simple: I instructed his teachers to put a cardboard box in the classroom, labeled “Billy’s Box,” and when it was time to transition to something else, to tell Billy “Put your paper in the box, and we promise you will be able to go back later and work on it some more, if you want to.” And that was the end of his tantrums.

----------------------------------------

These clinical summaries underscore the point that there are two prongs to perfectionism: The first, and more obvious prong is the need to get things “Just right” - an impossible goal, because no amount of effort is sufficient to achieve perfection. The second prong – often under-appreciated - is the incessant self-blame for failing to get things right. In the classroom this can take the form of outbursts (I had one child who repeatedly punched herself in the face for her perceived errors – even as she was executing the task at an adult level), or task refusal. Children (and adults!) with perfectionism often procrastinate, or attempt to avoid a task altogether, not out of “laziness,” but out of pre-emptive fear of failure, and fear of self-inflicted self-blame. Alas, teachers (and behaviorists) often do not understand this, and as a result they set up behavioral plans designed to instill “compliance to task,” rather than focusing on the child’s perfectionism and self-criticism. What’s needed is a positive behavior support plan for internalizing behavior, including perfectionism. That’s a story for another day.

Until then.