Happiness

Stoic Truths for a Digital World

Finding happiness in an always-on, consumer-soaked culture.

Posted October 14, 2016

** This article is being published to mark the start of Stocion 2016 and Stoic Week.

Every one of us wants to be happy. We want to be accepted and loved and carve for ourselves a life that feels worthwhile. We hope that when our final moment comes we will be able to look back over our lives and see that our time here has been well spent and has mattered.

Yet so often in the middle of it all, we look up from our commute, or from our chair in the study and see that somewhere, something has fallen short. At every turn there are advertisers, spokesmodels and PR firms ready to sell us a product or image that speaks to our vulnerabilities and dreams.

Without our noticing it, those promises and dreams have become expectations, the standards against which we judge ourselves, and the happiness we really wanted has slipped away.

Yet certain ancient truths persist. Teachings that did not wither in Alexandria’s flames or crumble with the papyrus scrolls worn thin by time. A wisdom that remains resolute and constant, despite the digital wizardry and onslaught of the always-on present. The Stoic philosophers of Greece and Rome tell us something about living the life we want to live.

White Noise

The information age is the age of white noise. With the 24/7 cycle of pseudo-events, news entertainment, staged reality programming, clickbait advertisements, do-it yourself broadcasting, et cetera ad nauseam, the digital biosphere feels more real than a day at the office and there is too much to choose. We expect to always be amazed, entertained, enraptured and fulfilled. But something novel and compelling rarely happens every hour of every day. News programs report that they are waiting for something to happen, or that a politician do not attend a debate. Our digital footprints last forever yet nothing is more permanent than the disappearing photos on Snapchat. Meanwhile we have traded our notions of character for Facebook profiles and the human-to-human dialog about issues, policies and programs that affect our lives have been reduced to screams and sound bites, or limited to 140 characters, including the blank spaces.

As a result, our hopes and expectations have become unrealistic and ungrounded. We expect our bathroom products to do the scrubbing for us. Soft drinks promise happiness and all we need is a little blue pill to have erections into ripe old age. Buff, shirtless men hawk yogurt and salad dressing. Lissome young women offer brownie mixes and headache remedies, all the while Photoshopping our image of what a woman should be. Everywhere, everyone is forever fertile, well-liked and intelligent. We can be too if only we use the right dish detergent, energy drink and body scrub.

A middle schooler with a smart phone has more information at her finger tips than did Aquinas and the church fathers in the whole of their lives. Technologies have brought seismic shifts in access, outreach, communication, productivity and economic opportunity. Diseases have been eradicated. Cures discovered. Literacy rates, access to clean water and health care, and countless other signs of our prosperous well-being, have been steadily rising too. Yet our levels of happiness have remained flat. Our rates of depression, negativity, anger and lack of trust are all increasing. Technology will not stop the brutality, terrorism, incivility or mistrust. What we need, is a collective change of heart.

This day-after-day, always-on media and advertising blitz, shifts the frame of what we see as average and ideal. It gives us a new sense of the matter-of-fact and normal. We expect lithe, nubile women to be everywhere. Men should be rugged and smart, sensitive and able to fix a leaking toilet. And somehow we have failed as parents unless our children win first prize, are on honor roll and acne-free. We have come to expect glittering perfection from our public figures, products, and selves. They should all, always be beautiful, brighter, better, faster and stronger. Yet as if there is no contradiction, we also expect the worst from the world. On the news and internet, we watch war-torn migrants capsize and drown, terrorists hold whole cities hostage, the police kill and are killed, genocides happen again-and-again, and there is a shameful normalcy to the modern slave trade. We expect life to be tragic and brutish as we helplessly retreat to the shopping mall. And among all the data flows and hundreds-of-thousands of search results, we hold tight to any truth that supports whatever halos we long for, or shadows we fear. Our confirmation bias has gone digital.

At the superficial-rational level, we know neither of these are true. But somewhere between the product placements and desire, our standards and visions of the world have become what the Gallup polls and click-based algorithms tell us.

Falling Short Feels Personal

When we don’t measure up, the failures feel personal. We have been told that we are all individual snowflakes and everyone gets a ribbon. Communication and data technologies have even flattened out to shift opportunity out to the margins and cul-de-sacs. Yet not all of our videos and vines go viral. The marriages that should have been perfect fail, and we don’t all get a raise. And as we kneel in the shadow of the idols we’ve praised, the advertisers are there with their $580 billion budgets to tell us how we could be happier, pain-free, younger-looking, and have softer skin. Immunity and immortality, it seems, are just a card swipe or click away.

As we sift through the white noise of progress, there are certain truths from antiquity that can aide in our making sense of things. Lessons from the Stoic philosophers of Greece and Rome can help us reap the very-real benefits of this digital era, and even lead to happiness.

The Stoics

Beginning in the third century BCE, the Stoics emphasized that every one of us has the ability to produce our own happiness. Our well-being, and a positive appraisal of our lives, does not depend upon the praise or opinion of others, consumer goods, renown or social rank. Happiness is not what is found on line.

Most of what we know of the earliest Stoics, Zeno (344–262 BCE), Cleanthes (d. 232 BCE) and Chrysippus (d. ca. 206 BCE) comes to us through the commentaries of others. It is not until Roman writers such as Seneca (4 BCE–65 CE), Epictetus (c. 55–135) and Marcus Aurelius (121–180) that we see complete texts on how to navigate our way in the world.

For the Stoics, philosophy was not just abstract ideas or anemic academic musings. It was a meaningful, pragmatic craft; one that offered practical guidance on how we should live our lives. Many of these truths have only increased in relevance today.

Happiness Is In Our Own Hands

First, the Stoics taught that happiness is in our own hands. Neither it, nor despair, result from external things. Our wellbeing and sense of shelter do not come from the good and bad events of our lives. Instead, all happiness begins and ends in virtue. "Moral goodness is the only good,” wrote Cicero “from which it follows that happiness depends on moral goodness and nothing else whatever." Despite what the advertisers say, there is so much in life that is out of our control. Good health declines. Fortunes fade. We cannot always protect our loved ones from pain or the demons of despair. We can, however, sharpen and balance the tools that enable us to stand strong and clearheaded in the sadness or trauma or pain. We can foster those qualities that help us savor the good things around us. We can learn to look at the world with the clear eyes and see things as they are, rather than as pollsters or doomsayers say. To be happy, we must develop those qualities of character that enable us to live with self-respect and thrive during the throes of life. When we cultivate strengths such as wisdom, justice, courage, and moderation, we can choose the best course of action for our healthy well-being despite all the noise and beautiful lies all around us.

Our Thoughts Are Only Thoughts

Second, the Stoics teach us how to see through that flood of images “brought to us by our sponsor.” The always-on advertisements, entertainers and political machines give us false impressions of what it means to live in the world. We want to believe the digital prophets and billion dollar promises. They give us hope or validate our fears. However, the Stoics remind us that our thoughts about things are different than the truth of those things. This is the basis of modern cognitive behavioral therapy. Someone says or does something, an event happens, Fortune smiles or frowns, and we bring to the moment the entire history of our expectations, aspirations and fears. So often our behavioral responses and emotional reactions are to our assumptions, hopes and suspicions, and not to what really happened. Your daughter is late on a stormy night and you are panicked at thoughts of a soggy ditch. But the ditch never did happen. If we recognize that our thoughts are only thoughts, we can bracket them off and look for what else might be true. We can avoid, as was taught by Epictetus, “the self-imposed slavery that is the result of taking external things to be genuine goods.” Then guided by our character, we can make choices directly that further our well-being, unaffected by the expectations, options, and criticisms of others.

The Stoics did not mean that we should no longer feel. Aurelius’ deeply personal writings at the edges of an empire under siege are filled with depression and hope. He longed for sympathy and affection, and so much more that is part of being human. However Aurelius recognized that “the soul becomes dyed with the color of its thoughts” and adopted a cognitive distance that enabled him to choose his actions deliberately and clearly. You can honor the hard facts of life, feel the vicissitudes, and yet also live in ways that contributes to your effective and affective well-being.

A Single, Connected Human Family

This inward glance toward one’s own character and thoughts does not mean that stoicism is a self-interested, egoistic philosophy. A third thing the Stoics remind us is that we are all connected. It is part of our nature to want to benefit one another. For Seneca, “nothing delights the mind so much as fine and loyal friendship.” Epictetus said that we are not just citizens of our own land, but are also members “of the great city of gods and men.” Hierocles described our relationships as concentric circles including self, family, kin, precinct, country and the whole of the human race. The aim is to pull each person toward the center, “deliberately transferring those in the outer circles to the inner ones.” More than two millennia before satellite phones, virtual reality and Skype, the Stoics talked of a single, connected human family.

And now at our fingertips and phones, we have the tools to bring about this shared and common kinship. Our cultures interact and overlap. We are connected economically, politically and socially. Whether in London or Lagos, Riyadh or Richmond, we share the same ideas and images we got from reruns of Dallas and Game of Thrones. The more global we become and the more connected, the more our fates rise and fall together.

Yet we remain ethically isolated. We continue to be lured by the advertisements and images, the biases and promises, that flicker across our computer screens. Whatever is placed into the networks spreads. So often, it is the worst aspects of society - anger, hostility, the false idols. As a result, the world becomes angrier, less trusting, more divided.

However, if we foster personal goodness and live in accordance with highest and best aspects of our character, we cannot help but place something else into the networks: courtesy and friendliness; mercy and gentleness; dignity; discretion; and humanity. Qualities such as these bind us to one another. It is the exercise of these strengths that transform small and large communities into alliances of confidants and friends.

Living in Accordance with Virtue

Technology connects us and brings so many good things about the world into our grasp. But it also delivers promises it cannot keep. It speaks to our basest and cheapest desires and leaves us awash in the worst aspects of humanity. As we try to make sense of things, it is easy to be tempted by the ideals and images that have been repackaged as adjuncts to our happiness. But so often the promises are just efforts to sell and promote, and rarely advance our wholesome wellbeing.

So despite whatever passions flare, regardless of the hopes we want to believe, the question becomes, “How do you want to live your life?”. If you live in accordance with virtue, you might get “likes” and “followers” and “retweets”. Others might notice you and validate what you are doing. However, they might not. But if we live from a standpoint of virtue, we will see that those things never really mattered.

The only things we can claim in life are our character and integrity. Never lower yourself because of circumstance or desire or fear. Unchain yourself from the standards set by others. When we align ourselves with the highest and best aspects of our nature, we are able “to increase our self-restraint, to curb luxury, to moderate ambition, to soften anger, to regard poverty without prejudice, to practice frugality . . . [and] to acquire our riches from ourselves rather than from Fortune.” It is through the exercise of virtue, that we find happiness.

References and Quotes

Cicero said "Moral goodness is the only good . . .” in Discussions at Tusculum.

Epictetus' line regarding “self-imposed slavery" is quoted from Stephens, W. O., 2007, Epictetus and Happiness as Freedom, London: Continuum, cited in Baltzly, Dirk, "Stoicism", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta

For a discussion of the emotional fullness and struggles Marcus Aurelius, see Introduction, Meditations (Trans., Maxwell Staniforth) Penguin, 1964

The description of Hierocles “deliberately transferring those in the outer circles to the inner ones” is quoted from Graver, Margaret R., Stoicism and Emotion (pp. 176-177). Kindle Edition.

The virtues discussed by Marcus Aurelius include Comitas (courtesy and friendliness); Clementia (mercy and gentleness); Dignitas (dignity); Prudentia (discretion); and Humanitas (humanity).

Seneca's line "to increase our self-restraint, to curb luxury" is found in On Tranquility of Mind, p. 88

Image Credits

Human being asking the Universe by CLUC/Flickr, made available via a Creative Commons, Attribution-NoDerivs license, Retrieved from flikr October 14, 2016.

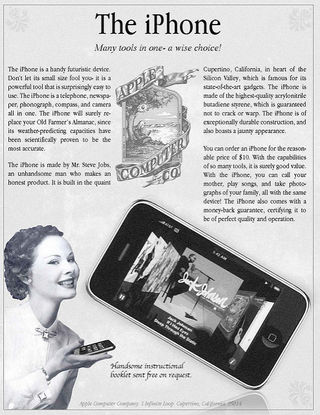

iPhone by Emily/Flickr, used under a Creative Commons, Attribution 2.0 Generic license. Retrieved from flickr October 14, 2016.

Buste cuirassé de Marc Aurèle âgé photographed by Pierre-Selim and made available via Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0. Retrieved from wikimedia.