Intelligence

Analogy, Insulting Hypocrisy, and Supreme Court Nominations

The faulty arguments for holding Amy Coney Barrett’s confirmation hearing.

Posted September 29, 2020

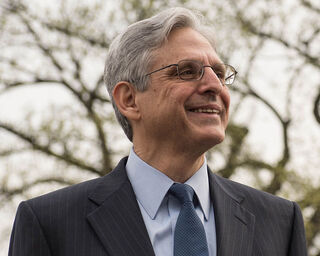

Trump’s nominee to the Supreme Court, Amy Coney Barett, met with Senate Majority leader Mitch McConnell and other Republican leaders today (Sept. 29, 2020). McConnell has vowed to hold her confirmation hearing before the election. But it’s no secret that when President Obama nominated Merrick Garland to the Supreme Court in March of 2016, a full eight months before the 2016 election, Mitch McConnell refused to hold a confirmation hearing, claiming that such appointments should never be made during an election year.

“The American people should have a voice in the selection of their next Supreme Court Justice. Therefore, this vacancy should not be filled until we have a new president.” –Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-KY) February 2016

And, at the time, his Republican colleagues agreed with him.

“It has been 80 years since a Supreme Court vacancy was nominated and confirmed in an election year. There is a long tradition that you don’t do this in an election year.” –Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX)

"The campaign is already underway. It is essential to the institution of the Senate and to the very health of our Republic to not launch our nation into a partisan, divisive confirmation battle during the very same time the American people are casting their ballots to elect our next president." –Sen. Thom Tillis (R-NC)

“In this election year, the American people will have an opportunity to have their say in the future direction of our country. For this reason, I believe the vacancy left open by Justice Antonin Scalia should not be filled until there is a new president.” –Sen. Richard Burr (R-NC)

“I think we’re too close to the election. The president who is elected in November should be the one who makes this decision.” –Sen. Cory Gardner (R-CO)

“I believe the best thing for the country is to trust the American people to weigh in on who should make a lifetime appointment that could reshape the Supreme Court for generations. This wouldn’t be unusual. It is common practice for the Senate to stop acting on lifetime appointments during the last year of a presidential term, and it’s been nearly 80 years since any president was permitted to immediately fill a vacancy that arose in a presidential election year.” –Sen. Rob Portman (R-OH)

"With the U.S. Supreme Court's balance at stake, and with the presidential election fewer than eight months away, it is wise to give the American people a more direct voice in the selection and confirmation of the next justice.” –Sen. Pat Toomey (R-PA)

Of course, it's also no secret that, when Ruth Bader Ginsburg died on Sept. 18 (a mere six weeks before the 2020 election), all these Republicans changed their tune. And to most, this is not only blatant hypocrisy—a refusal to apply their own standards to themselves—but a degrading insult to all our intelligence. But there have been attempts to justify this reversal. Consider, for example, the above quoted Pat Toomey’s recent form letter to his constituents on the matter:

“The circumstances surrounding the current vacancy are, in fact, different. While there is a presidential election this year, the White House and the Senate are currently both controlled by the same party. The Senate's historical practice has been to fill Supreme Court vacancies in these circumstances. … [So the] difference between these Senate practices makes perfect sense. When divided government creates tension between the two organs responsible for filling a position on the Supreme Court, it is completely justifiable to leave open a vacancy until the voters have had a chance to speak.”

What we have here is an argument from analogy—or, more specifically, an argument against an argument from analogy. The argument from analogy is that Republicans should refuse to hold hearings on Trump’s nomination just like they did for Obama’s in 2016.

- Republicans refused to hold confirmation hearings during 2016 because it was an election year.

- 2020 is an election year.

- So Republicans should refuse to hold confirmation hearings in 2020.

And it is to this argument that Republicans are objecting.

The primary way one criticizes arguments from analogy is by finding relevant differences between the two things being compared (in this case, the two election years) and suggesting these differences entail the conclusion does not follow. According to Toomey, the suggested difference is whether the White House and Senate are controlled by the same or different political parties. In 2016, they were controlled by different parties; in 2020 they are controlled by the same party. So, Toomey’s argument suggests, the above analogy doesn’t hold.

But such criticisms are legitimate only if the difference that is identified is actually relevant to the conclusion at hand, and in this case it clearly is not. Why? Because in all the Republican justifications for holding up the nomination in 2016, the only relevant fact that was mentioned was the fact that the nomination was happening during an election year. In 2016, no one anywhere said anything like:

“Because it’s an election year, and because The White House and the Senate are controlled by different parties, no appointments should be made. Otherwise it would be fine.”

No. The only relevant fact invoked was the fact that it was an election year—that the hearing was going to happen too close to the election. Therefore, other factors—like about whether the Senate and White House are controlled by different parties—are completely irrelevant.

Indeed, Republicans themselves recognized this at the time.

“I don’t think we should be moving on a nominee in the last year of this president’s term - I would say that if it was a Republican president.” –Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL.)

“I strongly support giving the American people a voice in choosing the next Supreme Court nominee by electing a new president. … I want you to use my words against me. If there’s a Republican president [elected] in 2016 and a vacancy occurs in the last year of the[ir] first term, you can say Lindsey Graham said, ‘Let’s let the next president, whoever it might be, make that nomination.’ And you could use my words against me and you’d be absolutely right.” –Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC)

What’s more, the only actually relevant difference between 2016 and 2020—the time between the hearing and the election—means that there is even more reason to not hold confirmation hearings for Barrett. Garland's confirmation hearing would have happened months before the election; Barrett’s will happen only a few days before the election. Given that the only reason Republicans invoked for holding up Garland’s confirmation in 2016 was its proximity to election day, and Barrett’s will be much closer than Garland’s would have been, the only relevant difference between 2016 and 2020 means that there is even more reason to not hold confirmation hearings in 2020.

To make matters worse, despite what Toomey suggests, it is not the "Senate’s historical practice [to] fill Supreme Court vacancies” during election years only when one party is in control. Election years have seen Supreme Court Nominations 12 times; five of those years had hearings under unified power; four had hearings under divided power (e.g., in 1988, Democrats confirmed Reagan's nominee Kennedy). Indeed, hearings were not held twice while control was unified; only once, in 2016, were hearings not held while power was divided.

Indeed, the “no judicial confirmations during an election year” rule that the republicans invoked in 2016 is known as the Thurmond Rule. And, although its status as an actual “rule” is a myth, it’s called the “Thurmond Rule” because Strom Thurmond invoked it in to try to block LBJ’s apportionment of Abe Fortas … in 1968 … when both The White House and Senate were controlled by the same party!

And as if to add insult to injury, Thurmond’s argument was that judicial appointments should not be allowed in election years, unless the nominee had bipartisan support from Senate committees and both parties’ leaders. Since Merrick Garland was someone that Republicans universally praised (until Obama nominated him), but Barrett is someone who Democrats largely opposed (even before her nomination), by the Thurmond rule—the very rule to which Republicans are appealing—they should have held a nomination confirmation hearing in 2016, but shouldn't now in 2020.

What’s more, Trump has made clear that he intends to legally contest (without evidence) the results of the election (if he loses), and the appointment of Barrett would likely decide things in his favor—but no such thing was true in 2016 about Obama (or Hillary Clinton). Consequently, by arguing that a hearing should have been held in 2016, but should not be in 2020, Democrats are not merely holding Republicans to the same standard that they set in 2016; one could argue that they are standing up for democracy itself.

So, in short, the Republican argument that this time it's different—that it was legitimate to refuse to hold a hearing for Garland in 2016 but is imperative that they do so in 2020 for Barrett—is so bad, that it is not only blatantly hypocritical, and factually inaccurate, but laughably fallacious—an actual insult to our intelligence.

Copyright 2020, David Kyle Johnson.