Friends

Is Instagram Making You Poor?

Social comparisons can bring us down. Here's how to channel that need.

Posted October 10, 2018

There’s a game I like to play whenever I feel the gut-punch of envy while scrolling through social media. I call it, “How much did that selfie cost?” I play this game to remind myself that many people, including my friends, are spending WAY TOO MUCH MONEY on things that don’t last, often racking up credit-card debt that will keep them up at night for months, all for the glory of that one fabulous photo.

How much did that selfie cost? Usually, the answer is, “Too much,” but that doesn’t necessarily stop us from feeling a twinge of pain when we look at these posts. In fact, evidence has been mounting for a while that social media may cause or increase depression1. Short of logging off completely, how’s a person supposed to deal with the onslaught of social comparisons that we face each time we check in with our friends and family? In this article, I'll talk about why we NEED (yes, need) to compare ourselves, and how we can do it in a healthy way.

Comparisons are inevitable

Some people advocate a lifestyle free of comparisons. Just stop, they say, and you’ll be happier and healthier. That’s a nice sentiment, but not very practical. First of all, even if you cut yourself off from all social media, you would still have the daily reminder of other people’s lives and money through their cars, clothes, houses, etc. Long before social media, the Joneses were the target of envy. Now, we have the Joneses, the Kardashians, and everyone in between, but regardless of how or to whom we are comparing, the very ACT of comparing ourselves with others is an innate human activity, and to suggest that we can just stop is to deny the reality of human nature.

Back in the 1950’s Leon Festinger wrote a groundbreaking paper on Social Comparison Theory2 that has since become the foundation of an entire branch of psychology. In this work, he laid out considerable evidence for two ideas.

1. “There exists, in the human organism, a drive to evaluate his opinions and his abilities.”3

Simply put, we want to know how we measure up. We need to have a sense of how well we are living; how successfully we are doing this thing called life. The standards by which we judge ourselves may differ wildly depending on our time, our culture, our age, our tastes, etc. but the need to evaluate our life’s progress by some standard is innate and can’t be removed. It’s natural and can be healthy if done right (more on this later).

2. “To the extent that objective, non-social means are not available, people evaluate their opinions and abilities by comparison respectively with the opinions and abilities of others.”3

There is no objective standard that defines what it means to live well. I can measure my health by objective standards like BMI, cholesterol, blood pressure, and the presence or absence of disease. When it comes to lifestyle, there is no metric that marks the line where someone is considered successful. Rather, we are left to define success for ourselves, and often we use our friends, family, colleagues, and even strangers as the scale by which we measure our progress. This can be a problem when it comes to our financial lives.

Comparisons can be toxic

The problem isn’t that we compare ourselves, it’s WHO we choose as the target for comparison. I recently surveyed a group of people about their financial lives, their financial comparisons, and their emotional well-being. What I found was quite interesting.

We tend to compare up, and that brings us down.

Regardless of how poor or wealthy people were, most of them tended to compare themselves with those they thought were better off4. That's understandable when you are on the bottom of the economic ladder (there’s nowhere to look but up), but even those earning top salaries were more likely to judge themselves against those with more. Maybe we think that by looking at those further up the ladder we’ll be motivated to improve ourselves? That’s possible, but the effect of upward comparisons was fairly toxic, from what I could see.

In every income group, people who reported making frequent, upward comparisons also reported having more debt, lower savings, higher stress levels, and lower satisfaction with their own situation than people who compared themselves with those less fortunate. When asked about the emotions they experienced in their own financial lives, people who compared upward were experiencing significantly more negative feelings than those who did not.

Clearly, comparing up isn’t doing us any favors. This suggests that when we scan Instagram or Facebook and judge our own lives by the way they compare to those dream vacation photos and shiny new cars all our friends are enjoying, we may be actively sabotaging our own finances. But if Festinger was right, and social comparisons are inevitable, then how are we supposed to avoid doing damage to our hearts and our wallets?

The Exception to the Rule

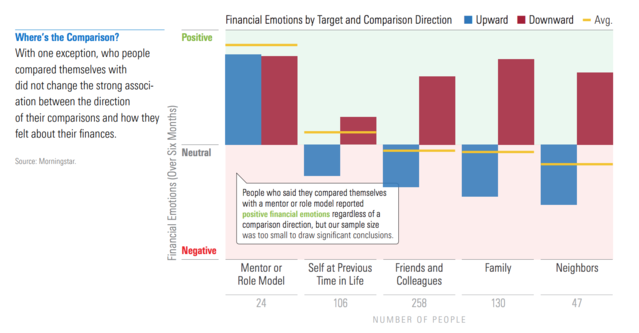

In my study, there was a small group that defied the trend. Most people said that they usually compared themselves to a friend, family member, neighbor or colleague. All of these comparison targets followed the same trend: upward comparisons were most common, and they were associated with lower financial well-being.

The exception to the rule was a small group of people who said they compare themselves to a role model or mentor. In this group, regardless of whether the role model was better or worse off, financially, the person making the comparison tended to feel good about their own financial life. Not just good, but compared to the rest of the bunch, they felt great!

I followed this study with an experiment where I asked one group of people to choose a financial role model and answer a few questions about them while another group answered questions about their normal comparison targets. Both groups then answered questions about their financial habits and emotions.

The people who thought about a role model were significantly more confident and felt more in control of their financial lives after the exercise than the people who made their normal comparisons. This suggests that, while we can’t get rid of our need to compare, we might be able to make those comparisons work FOR us and not against us.

How to choose a role model (and not have it backfire)

Research into the effects of role models on confidence and behavior suggests that we need to take care when we choose a role model, or the results can backfire5. Penelope Lockwood is a giant in this area of research, and her work suggests that people need to be careful when choosing a role model. According to the results of her studies, people who choose a role model whose success is far beyond what they themselves believe they can realistically achieve can actually become demoralized rather than energized by the comparison. This is why Warren Buffet is probably not a good financial role model. Unless what you admire and want to emulate is his humility and habit of living below his means, then using him as your comparison target will probably do you more harm than good.

So, RIGHT NOW, think about someone whose financial life or behavior you admire. You don’t need to know them or their finances well. The point is to find someone whose lifestyle you admire (even if you only have a glimpse), and that you think you can realistically achieve for yourself over time. Make sure the goal you are setting is realistic, positive, and practical. Anecdotally, when I have done this exercise with strangers, be they online survey participants, friends, colleagues, or financial advisors, there are two things that people seem to admire most:

1. Contentment.

2. A lack of stress over money.

These characteristics likely go hand in hand.

Once you have someone in mind, ask yourself the following questions:

1. What is it about their financial life or behavior that you admire?

2. What qualities or values do you think have led them to their current situation?

3. Do you have (or can you cultivate) any of those qualities or values?

4. What is ONE small thing you can do RIGHT AWAY to be just a little more like them, financially?

5. Picture yourself doing that one thing, even just once.

Role models can help channel our natural need to compare into an action-oriented energy that helps us to make progress toward a real goal. By redirecting our toxic comparisons to this role model, we can (hopefully) avoid the overspending (or under-saving) that can come from trying to keep up with the expensive selfie habits of the masses.

Conclusion

The next time you come across that gut-punch Instagram post, catch yourself. Take a breath and think about the person you just named above. Remind yourself of the qualities you admire in them, and of the good things that are around the corner for you by following in their footsteps. Maybe, then, that expensive selfie won’t seem quite so admirable in comparison.

References

1. Kross E, Verduyn P, Demiralp E, Park J, Lee DS, Lin N, et al. (2013) Facebook Use Predicts Declines in Subjective Well-Being in Young Adults. PLoS ONE 8(8): e69841. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069841.

2. Festinger L (1954). “A theory of social comparison processes.” Human relations. 7 (2): 117–140. Doi: 10.1177/001872675400700202.

3. Ibid p. 117-118

4. Newcomb (2018) The Comparison Trap: How Social Comparisons Affect our Financial Well-being, Morningstar, Inc. White paper.

5. Lockwood, P. and Kunda, Z. (1997) Superstars and Me: Predicting the Impact of Role Models on the Self, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 73, No. 1, 91-103. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.578.7014&rep=r…