Relationships

2 Must-Have Ingredients for Helping Others Grow

What research and practice tells us about the most effective support styles.

Posted September 23, 2020

Those in helping professions, such as teachers, doctors, mentors, often say that serving, supporting, or facilitating the development of others is the greatest honor of their lives. Whether you’re hoping to help others grow as a manager, a parent, a teacher, or a peer, you need two ingredients to succeed: love and belief. Without these ingredients, others may still succeed, but it will be in spite of you, not because of you.

To be clear, the development of others isn’t ever something you do for them. The locus of control and responsibility always resides in the person doing the changing. That said, growth, success, and development don’t happen in a vacuum. If you hope to lend a hand in positive change, make sure you’re including the following foundations.

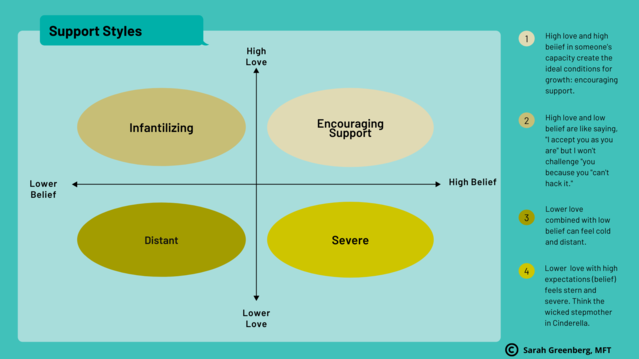

Support styles matrix

Here’s a little two-by-two I created to show these two core ingredients define our support style. Love can be thought of as caring and acceptance. Belief is interchangeable with expectation.

High love, high belief (top right quadrant) is when we feel and express caring and acceptance, while simultaneously holding high expectations for what others are capable of.

The effectiveness of this approach transcends disciplines. In the parenting realm, this state best aligns with “authoritative parenting,” which research shows is the best style for rearing children who are independent, well-adjusted, and successful. I use the phrase, high love, high expectations because the term “authoritative” really connotes raising kids.

High love, low expectations is when we feel and express caring and acceptance, but don’t really trust others to navigate their responsibilities. As a result, we may “infantilize” our the adults we hope to serve. “Infantalize,” a term that goes back to the 1940s, means treating someone “in a way that denies their maturity in age or experience.” This can foster unnecessary reliance, learned helplessness, and general lack of thriving. In the workplace, it feels condescending.

Low love, low expectations cultivates distance. This is not a good way to show someone that you are in their corner. It may align with Laissez-faire management styles, which research suggests are not effective.

Low love, high expectations cultivates a sense of severity and coldness. An exaggerated version of this might be the wicked stepmother in Cinderella.

Read on for why I see these dimensions as critically important for anyone who wants to be a facilitator of others’ development.

Belief

In 1965, two social scientists, Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson, administered psychometric tests at an elementary school in California. Based on these tests, they informed the teachers that they identified the “growth spurters”—the students who were most likely to “bloom” academically. A year later, these “growth spurters” indeed blossomed.

But before you start guessing at the "growth spurters" in your life, know this: The test was fake. Unbeknownst to the teachers, the “growth spurters” were selected by the two researchers at random. So the only real difference between the “growth spurters” and the rest of the students was in the minds of the teachers.

This groundbreaking study was among the first to offer clear evidence of the Pygmalion Effect—the phenomenon that expectations become a self-fulfilling prophecy. It has since been demonstrated in sport, in the military, and in the workplace.

What we expect from others influences what we get from others, for better or worse. The impact of "belief" comes down to a small, but critical mindset shift. If you want to help others grow and change, look within. Ensure you are truly holding generous expectations for the humans you are working with. If you are human, this will likely be easier to do with some than with others. Do the hard internal work to shift this and you will shift your impact.

Love

I speak not of romantic love, but of a fundamental human love that is based on genuine care, respect, and acceptance. If you don’t like the term “love” sub in “nurture,” "acceptance," or “caring.” When we seek “to change someone” because we feel they need to change, it’s neither kind nor effective. “I care about you, now change,” is simply not an approach that works.

Part of this is because it’s not our job to change others. As Carl Rogers, one of the founders of Humanistic Psychology, wrote, “In my early professional years, I was asking the question: How can I treat, or cure, or change this person? Now I would phrase the question in this way: How can I provide a relationship which this person may use for [their] own personal growth?” The most successful facilitators of growth don’t do the growth for others; they provide the atmosphere in which others have space to grow.

Part of this is because of the paradox of change: Change begins with full acceptance of one’s current state. In other words, as a former teacher of mine used to say, “You can’t get anywhere from not here.” This importance of beginning from a place of acceptance is everywhere–from wisdom traditions such as mindfulness to popular programs such as 12-step. Western psychology owes a debt of gratitude to Carl Rogers for integrating this truth into modern psychotherapy. He wrote, “The curious paradox is that when I accept myself just as I am, then I can change.”

Final thoughts

Think back to a time when someone else helped you grow in a positive direction. Did this person embody love (acceptance and caring) and belief (high expectations)? Or perhaps they didn't believe in you, and you set out to prove them wrong — thus, succeeding in spite of them? What other ingredients helped you succeed?

Love and belief are flour and water. Without these, you just won't get the optimal impact (the bread) you hope to make. But there are many other ingredients that matter too. Which ones are important to you? Which do you want to embody?