Fear

Protecting Your Own Cyber Security During the Russian Invasion

How the illusion of invulnerability clouds accurate self-assessment of risk.

Posted March 11, 2022 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- We tend to underestimate the risk to our own cybersecurity.

- Be on guard for spear phishing attempts.

- We can improve our security by updating software, using strong passwords, a password manager, and multi-factor authentication.

Russia's war on the Ukrainian people has taken to the streets, to the skies, but also to the cloud. Less than two weeks ago, the Ukrainian government put out a call for volunteer hackers to help defend the country's cyber infrastructure, and Western allies sent intelligence specialists to the country to help.

How Our Security is Hacked

Conti, a Russia-based group of hackers and ransomware developers, works by gaining remote access to our devices. It pays a wage to individuals to deploy ransomware in addition to offering a share of the profits from successful attacks, making participation in the group doubly lucrative.

Attackers gain initial access to networks through spear-phishing campaigns that tailor emails to potential victims, distributing notes that seemingly originate from known and trusted senders. The correspondence contains malicious attachments or links with embedded scripts that drop malware connecting a victim's device to Conti’s command-and-control server.

Once inside, hackers steal documents, encrypt devices and their contents, and demand a ransom payment to free the hijacked files and locked down systems. The attackers threaten to make the data publicly available unless they get paid.

Protections and Why They Don't Work

What do organizations do to protect against these kinds of phishing schemes? One of the most common approaches is to forewarn individuals of danger by sharing base rates on the susceptibility of attack. In a 2019 briefing, Proofpoint, a leading cybersecurity company, reported that 83 percent of more than 7,000 adults in seven countries experienced a phishing attack the year before. Security companies, like Proofpoint, present these base rates to incite fear and an urgent need for self-protection.

Unfortunately, communicating these types of statistics does little to reduce people's inflated sense of personal security and complacency research my colleagues, Blair Cox, Quanyan Zhu, and I published in 2020 show. People continue to believe the odds of someone else clicking on a malicious link, accidentally downloading trojan software, or engaging with a would-be attacker are higher—in fact about 50 percent higher—than they think it is for themselves. It's as if we are living under an illusion of invulnerability.

Back in the early 1980's, social psychologist Linda Perloff discovered that people believe they are safeguarded from the dangers and misfortunes of life that afflict other people. That's why people don't wear seat belts or use condoms at the rates they should.

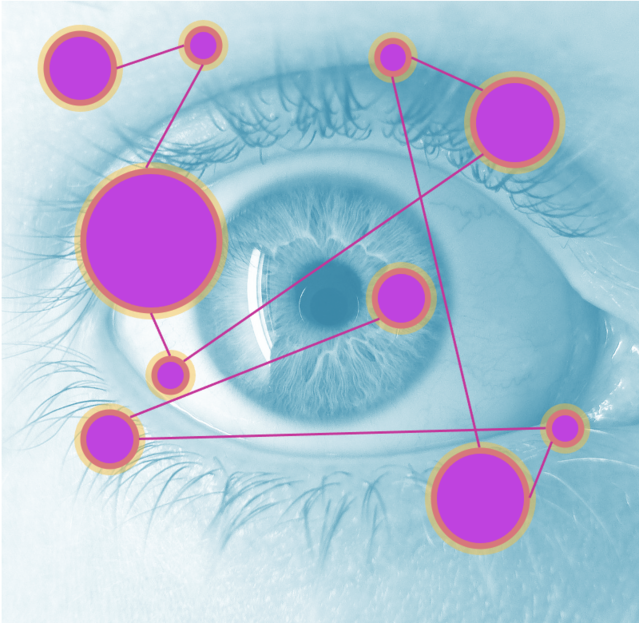

Our research also discovered that the same illusion might be responsible for the poor assessments of personal cyber security, and our research found out why. Using covert eye-tracking technology that monitored where people looked without them knowing that we were tracking their gaze, we discovered that people look about 14 percent more often at statistics that communicate whether the odds of attack are large or small when thinking about other people compared to themselves. People act—wrongly—as if these base rates aren't personally relevant or meaningful.

What Can You Do To Keep Yourself Cyber Safe

To combat the rise in attacks, the United States' Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) launched its Shields-Up Campaign, which offers four steps to maintaining cyber hygiene.

First, slow down and think before you click. CISA finds that 90 percent of successful cyber-attacks start with a phishing email that includes a link or webpage that looks legitimate but is actually a trick designed by would-be attackers to get us to disclose our passwords, usernames, and personally-identifying information like social security, bank account, or credit card numbers. Trust your instincts. If something looks fishy, it might be phishy.

Second, we can update our software with patches that address known exploited vulnerabilities. Keep automatic updating turned on and follow through with recommendations to update software.

Third, use strong passwords. Unique, complex, random string passwords are the least susceptible to hacking. Store computer-generated, hard-to-remember strings of letters, numbers, and symbols with a password manager. But a strong password isn't enough. Adding a second layer of identification, like a confirmation by way of text message or email, a code from an authentication app, a fingerprint or Face ID, or a FIDO key, substantially reduces the odds you get hacked.

Finally, Shields-Up also encourages federal, state, local, tribal and territorial governments, as well as public and private sector critical infrastructure organizations to sign up for free cyber hygiene services. CISA can provide a phishing campaign assessment that determines the potential susceptibility of personnel to phishing attacks and measures the effectiveness of security awareness training.

Even if you or your country is not at war, we all might be standing one click away from being collateral damage.

References

Cox, E. B., Zhu, Q., & Balcetis, E. (2020). Stuck on a phishing lure: Differential use of base rates in self and social judgments of susceptibility to cyber risk. Comprehensive Results in Social Psychology, 4(1), 25-52.