Psychology

How Can We Combat "Compassion Fade"?

The psychology of comprehending large numbers in crisis

Posted March 25, 2021 Reviewed by Matt Huston

- As the number of victims increases, people's motivation to help can wane—something psychologists have called "compassion fade."

- Compassion fade runs counter to what people might expect about how they would respond to a crisis.

- Visually representing groups of victims as a single unit may increase the impact on viewers and their willingness to provide support.

On February 21, 2021, The New York Times published a rectangle of dots on its front page. Five hundred thousand dots. Why? Each dot represented one life lost to COVID-19. It was a concrete visual representation of an otherwise intangible statistic—a statistic that keeps growing. In the 20 days since that cover image was published, the CDC has reported the deaths of another 29,301 people.

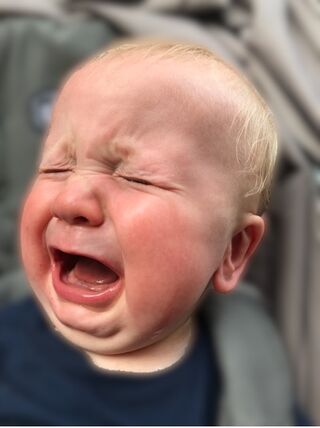

Such visualization tactics work to inspire efforts to change a problem. Behavioral science researchers tested the impact of adding visual images to charitable appeals to improve the humanitarian crisis for children in Syria's civil war. Compared to when it had no images, the appeal that included a picture of an injured boy in an ambulance following an airstrike increased the amount of money donors contributed. A picture of a single child in desperation pulls at our heartstrings and our wallets.

But human hearts can be tapped out. As the number of victims increases, motivation to contribute to solutions to a crisis starts to wane. Psychologists have called this troubling phenomenon "compassion fade." For example, a team of researchers from the University of Oregon found that individuals donated 12 percent less when a charity campaign described the food scarcity experienced by many children compared to when the appeal focused on just one.

This human tendency is disturbing for many reasons. First, it flies in the face of what most people think about how we should value the lives of others in need. As need increases, so too should our response to mitigate the emergency. Second, it contradicts our intuitions about what we think we would do in response to a growing crisis. Finally, it suggests that to combat large-scale health pandemics, we need to surmount not only political and economic obstacles but also psychological ones.

We have a sizable capacity to care for others but it can be challenging to engage it, particularly as the scope of the problem increases. How can we combat compassion fade as the toll of the current pandemic continues to grow larger?

Making Big Numbers More Meaningful

When the number of deaths is as large as it is now, it is impossible to craft a vivid picture of each and every one of the individuals lost and all of their affected families. Instead, thinking of the departed as a single unit reengages compassion. The Times took half a million dots and represented them as a single rectangle, and research finds this kind of visual aggregation tactic to be one that effectively fights compassion fade.

The team of researchers mentioned earlier found that donors were willing to pay $20 to assist eight Syrian children when images of those children appeared sequentially, as if the children were unrelated to one another. However, donors were willing to pay $32 if those eight children appeared in a single photograph and were described as a family. Depicting the victims as a single unit raised concern and assistance.

The White House, too, seems to understand the value of thinking of large numbers as a singular unit. They used this visual technique as a part of the first official national commemoration of COVID deaths. The day after the Times dots cover, President Biden and Vice President Harris, and their spouses, marked this grim milestone by lighting a single collection of 500 candles on one set of stairs on the South Portico of the White House and acknowledged the totality of the loss experienced.

It is likely impossible to forget that people are dying every day. The challenge for us personally is to continue to care.