Relationships

Mindful Music: Listen, Learn, and Love!

Sit down, take a moment, and really listen to music.

Posted May 4, 2020

With earbuds, smartphones, and streaming apps, many of us spend considerable time in the presence of music. Yet generally, it’s background fodder as we engage ourselves with other tasks, such as preparing a meal, exercising, or casually grazing on newsfeeds. Our time with music reminds me of the line in Simon and Garfunkle’s song, The Sound of Silence—"people hearing without listening.”

During our extended “time-out” this spring, I’ve been sitting in a comfy chair with good headphones and really listening to music—from Ray Charles to Henryk Górecki. The experience has made me think about the multifaceted ways music affects us psychologically. On the one hand, music is universal as every culture revels in it, and its emotional impact appears direct, bringing tears to our eyes or sending chills down our spine. On the other hand, cultures vary widely as to the sounds, melodies, and instruments used to create what can be called music.

Indeed, a tune that affects one person deeply may do nothing for another. As pervasive as music is, it is clearly an acquired taste—based significantly on cultural and personal experiences. Some are inspired by opera, while others love Country Western music.

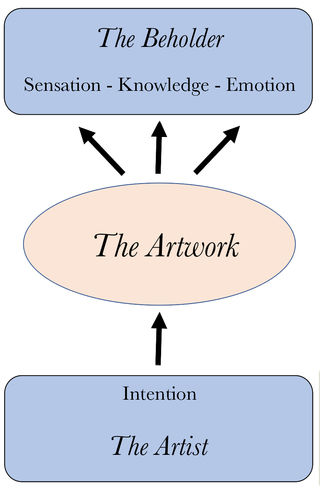

In my writings about the psychology of the visual arts, I have focused on how we—as beholders—experience art. We all agree that art is a sensual and emotional experience, yet we don’t always appreciate how much knowledge and prior experiences drive our sensations and feelings. In my I-SKE framework of art experiences (see figure), The Artist creates an Artwork with the Intention of driving Sensations, Knowledge, and Emotions in The Beholder. I argue that a heightened art experience (that “wow” feeling) occurs when all three psychological processes are driven to the max.

Knowledge influences our art experience in many ways. It directs us to pertinent perceptual features. It can also drive emotional responses.

Years ago, on a visit to the de Young Museum in San Francisco, I came upon a curious installation comprised of pieces of black wood hanging from wires. Reading the placard next to the piece, I learned that the artwork, titled Anti-Mass, was created by British artist Cornelia Parker, who constructed the work from the charred remains of a Southern Baptist Church that was burned down by racist arsonists. This knowledge suddenly turned an intriguing visual display into a wholly emotional experience that brought tears to my eyes.

Listen! In the span of just a few minutes (or longer, if desired), music offers a mindful experience that can capture our sensations, thoughts, and feelings in glorious fashion. Much has been discovered about the brain mechanisms associated with our music experience (see Robert Zatorre’s TED Talk, From Perception to Pleasure: How Music Changes the Brain, and Daniel Levitin’s book, This Is Your Brain on Music). With respect to personal knowledge and prior experiences, many songs have become part of the “soundtrack” of our lives as they cue memories of our past.

Certain songs are firmly associated with a specific time and place from our past and are thus intertwined with emotions felt at that time—perhaps related to a celebration, coming-of-age moment, or traumatic event. Some songs—like Georgia On My Mind, Take Me Home, Country Roads, and Carolina In My Mind—spark nostalgic memories of my hometown, even though the specific locations mentioned in these songs are far from where I grew up. Other melodies induce feelings directly, such as the calming effect of a slow, lyrical piece or the energizing feeling of a fast-paced dance tune (see Palmer, Schloss, Xu, & Prado-León, 2013 for a psychological analysis of emotion and features of music).

Learn! As with my encounter with Cornelia Parker’s Anti-Mass, learning about an artwork enriches the experience both intellectually and emotionally. With internet access at our fingertips, it is easy to gain knowledge about any genre of music, artist, or specific tune. Documentaries, tutorials, and interviews are available on video streaming services, such as YouTube.

I particularly enjoy presentations by Leonard Bernstein, the renowned orchestral conductor, whose insightful analyses and musical demonstrations can be seen on his early television program, Young People’s Concert, his appearances on the TV show Omnibus, and his various public lectures and performances (many available on YouTube). Last week, I listened to Bernstein’s Young People’s Concert tribute to Leon Sibelius, the Finnish composer. Bernstein helps us understand the thematic motifs underlying the music, performs several of Sibelius’s works, and discusses the political-cultural context that made the composer such an important figure in Finland. In just an eight-minute segment of this program, Bernstein shows how a simple three-note motif is intricately woven in Sibelius’s Symphony #2. His performance of the last movement is felt so much more deeply as Bernstein tells us that “for the people of Finland, this ending only means one thing—freedom.”

Love! I’m in love with Pohjola’s Daughter, Sibelius’s 1906 symphonic tone poem. Having heard it for the first time last week, it is now a daily love affair, not unlike my childhood encounters with Beatles songs and other rock and roll hits. The Finnish myth of Pohjola’s Daughter is a story about the old and bearded hero, Väinämöinen, who, on his journey home, sees the fair maiden above a rainbow, weaving a cloth of gold. Väinämöinen asks her to descend and join him, but is ultimately rejected and must continue his journey alone and disappointed.

The music begins with a slow, lyrical motif played by a cello and develops with intertwining oboes and violins. Like a heroic tale, there are moments of tension and release with a fiery climax, which is followed by a peaceful ending. It is satisfying to break out of my standard playlist of old and familiar tunes and encounter such a lovely piece of music for the first time.

Perhaps a silver lining of this pandemic cloud is that we have been forced to spend time evaluating our situation. I suggest taking some mindful moments listening, learning, and falling in love with music. Expand the experience by gaining knowledge about the music you enjoy.

Ask yourself the aesthetic question: "Why do I like it?" What sensual qualities drive my interest—rhythm, melody, instrumentation? Does the music remind me of past experiences? What feelings are generated? What are my favorite songs?

I remember enjoying "Desert Island Discs," a section in the free weekly magazine, Pulse, published by Tower Records (some might remember record stores). In it, people listed the 10 albums they would bring if stranded on a desert island (I’ve since learned that this idea was lifted from a BBC radio program). It’s a fun topic of conversation to share with others—yours and their desert island discs (novels or movies). It offers a way to discover new works… so consider asking family and friends, "What do you like?"

Art’s Desert Island Discs

- Bach: Cello Suites, Pablo Casals

- Beethoven: Late String Quartets, Quartetto Italiano

- The Cache Valley Drifters, Vintage Drifters Live in Los Angeles, 1979

- Gal Costa: Canta Tom Jobim

- Bob Dylan: Blood on the Tracks

- Everything But the Girl: Idlewild

- The Grateful Dead: Reckoning

- Dennis Kamakahi: 'Ohana

- Joni Mitchell: Miles of Aisles

- John Renbourn: Another Monday