Bias

Using Harry Potter to Address Racial and Other Prejudices

With so much racial tension in the news, Harry Potter research offers answers.

Posted September 23, 2016

I usually enjoy listening to the radio while I cook dinner, but lately I literally cannot stomach it. It seems that whenever I tune in, the airwaves are full of bad news. From stories about politics to Flint, MI, to police shootings, I often imagine that my colleagues who are therapists must have a line snaking around their office buildings of people who feel anxiety over these troubling times. Of course we want to keep up with the latest news. In this blog entry, I relate some recent science news that is uplifting and also applies to the troubles we hear about in the press.

I study the role of story in our psychological lives, from film and television to books and video games. I also do research on how we talk about race, gender and other social groups in the media. I’ve noticed that many people say that film, television and books are ways to escape, but that they don’t mean much other than that. In these troubling times, can we look deeper and see what these story worlds can do for us other than simple entertainment?

Here’s the story of how our favorite stories, including Harry Potter play a real role in our psychological and social well being. Yes, they are fiction – works of art – and yes, they also can make a difference – maybe more so than the political alarms that we usually hear.

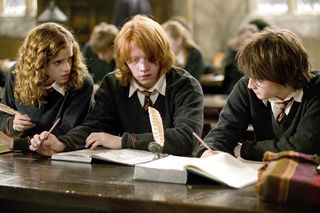

In a recent article titled “The real magic of Harry Potter: Reducing prejudice,” scientists (1) demonstrated the importance of a particular story – Harry Potter -- in real life. They studied elementary and high school children and university students, conducting research in the UK and Italy.

In one study, teachers read portions of the Harry Potter series that related to prejudice against fictional groups (e.g., “Mudbloods” who have parents of mixed fictional heritage) or read portions that were unrelated to prejudice. Results showed that those who had read and discussed the content on prejudice with their teachers were less prejudiced against immigrants those who had not covered the parts of the stories related to prejudice. This effect only worked for those who identified with the hero (Harry Potter) and who did not identify with the villain (Voldemort).

In a second study, researchers found that high school students who had read Harry Potter and who identified with him and not Voldemort were less likely to be prejudiced against homosexuals than those who had not read the books. In a third study, university students who had read the Harry Potter novels and who had taken the perspective of Harry were less prejudiced against refugees than those who had not read the novels.

In another investigation (2), scholars studied English children and their attitudes towards refugees. They found that reading story books to the children in which English children were friends with refugee children reduced prejudice compared with children who read other stories. These studies are thought to work through the “extended contact hypothesis.” In other words, just the idea – even expressed in story books – that people like me are friends with people from another social group – makes a difference in the real world.

In both of these sets of studies, young people showed less prejudice if they connected more closely to the characters. The researchers who studied Harry Potter said that a key factor behind the results is what they call “inclusion of self in other.” In other words, if I can see you as a part of me, I might apply the golden rule to you – treating you as I would like to be treated.

Of course it is important to follow the news, even the bad news. But, I wish that when I turned on the radio in the kitchen, what I heard reflected less of the seemingly endless barrage of terrible news without offering solutions, and more of what is hopeful or that offers solutions. Whether or not we tune into Harry Potter to escape, when we spend time there, it can give us the tools to make a difference. Clearly, the world is in need of more of this kind of perspective.

References

(1) Vezzali, L., Hewstone, M., Capozza, D., Giovannini, D., & Wölfer, R. (2014). Improving intergroup relations with extended and vicarious forms of indirect contact. European Review of Social Psychology, 25(1), 314–389. http://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2014.982948

(2) Cameron, L., Rutland, A., Brown, R., & Douch, R. (2016). Changing Children’ s Intergroup Attitudes toward Refugees : Testing Different Models of Extended Contact Author ( s ): Lindsey Cameron , Adam Rutland , Rebecca Douch and Rupert Brown Source : Child Development , Vol . 77 , No . 5, Special Issue on Race, 77(5), 1208–1219.