Depression

The Mother’s Depression and the Child’s Heart

How maternal mental health and an infant's temperment interact.

Posted November 19, 2022 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Key points

- Mothers often experience postpartum depression after giving birth. This can influence their families.

- The ability to self-regulate can be measured at the physiological level through patterns of heart rate variability.

- When a mother had postpartum depression and their infants were less well-regulated (as measured physiologically), the mother had worse outcomes.

- Mothers can influence infant mental health, but this study also shows that difficult infants can influence mothers' mental health.

Delivering a baby can trigger many emotions in mothers. Although a new birth often brings joy, it can also often bring feelings of depression. According to recent statistics, around 1 in 10—and maybe as many as 1 in 7—mothers will experience postpartum depression in the year after their baby is born (postpartum just means “after birth”). This depression typically lasts 3 to 6 months, but can be longer. For a third to a half of women, this postpartum depression can lead to a chronic or recurring depression.

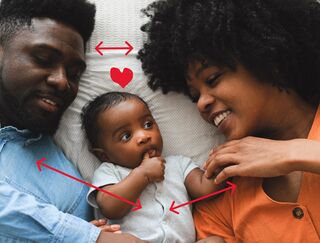

Postpartum depression is also related to the way that mothers and children interact, and the way the caregiving relationship unfolds. Babies are born with individual temperaments, with some expressing more negative emotions and having a harder time soothing themselves. Babies with these less regulated temperaments can actually change how mothers feel about themselves as parents, having downstream consequences. Relatively recent research explores the underlying physiological basis of this effect.

According to decades of theory and measurements, patterns of heart rate variability are related to people’s ability to regulate their emotions. That is, a tendency to be able to flexibly adapt to stressful situations and to deal with your own feelings is reflected in the patterning of your heartbeats over time. There are many ways of estimating heart rate variability, but one of the most widely used is estimating Respiratory Sinus Arrythmia (RSA). This measure tries to isolate activity of the parasympathetic “rest and digest” system, as it influences the heart. Previous work found that infants with lower RSA displayed more negativity and reacted more to new situations. Current thinking therefore suggests that RSA might be a basic, physiological indicator of poor self-regulation in infants.

Researchers followed mothers for 3 years after the birth of their child, taking periodic measurements of both the mothers and the infants. Using these measures, they constructed a statistical model of the process they believed was unfolding in the mother-child relationship. Key to this process was an appreciation of how postpartum depression in mothers and poor self-regulation in infants combined:

- Mothers had varying levels of postpartum depression after giving birth.

- Infants varied in their natural, physiological regulation. (This was measured by the RSA.)

- If mothers were high in postpartum depression, and their infants naturally had a hard time regulating themselves, then there were several negative outcomes.

- The negative outcomes included mothers feeling less confident in their ability to be good parents, and mothers having worse depression symptoms 3 years later.

We can think, then, of the mother and infant as influencing each other. If an infant was “easy,” then postpartum depression didn’t matter as much. Mothers still felt confident in their ability to parent, and they didn’t end up with higher levels of depression 3 years later.

On the other hand, if the infant was more reactive and less able to soothe itself, then postpartum depression did matter. When the infant was naturally more “difficult,” then mothers with more depression ended up feeling less confident and having depression symptoms that lasted longer (e.g., out to the 3 year mark). This shows how both the mother’s state of mind after birth and the infant’s physiology contribute to the way the mother feels throughout the child’s early years.

Discussions of maternal mental health and parenting can lead to strong feelings. Many parents worry about whether they are doing “enough” or “the right things” to make sure their children are healthy and happy. This research offers a few lessons related to these concerns. First, it is normal to feel sad and even depressed after childbirth. Many women feel this way, and even if someone is not diagnosed with postpartum depression, they may have some “baby blues” for a while after the birth.

Second, a strong bond is only partially under the control of the parent. Children are born with their own personalities, and with differences in their physiology. This can have a real effect on how the relationship unfolds. Infants that are fussy might present more challenges for mothers, and that can lead to very different experiences. Parenting might feel harder just because of the genetic luck of the draw. This is important to remember when comparing parenting between people. What might be easy or right for one mother wouldn’t work for another. This isn’t because of their capacities to be good mothers, but because of the needs and demands of their particular babies.

References

Somers, J. A., Curci, S. G., & Luecken, L. J. (2021). Infant vagal tone and maternal depressive symptoms: A bottom-up perspective. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 50(1), 105-117.