People who don’t watch or read horror stories might think that female characters therein are mere helpless victims, running around (in lingerie) to the sound of chainsaws. I’ve written elsewhere about how nothing could be further from the truth so I won't say too much about that here. Briefly: The figure of the Final Girl—the wise brave savior who is the only one to make it to the end of the story—exists across time and space. She even gets her own name in TV tropes, so common is she.

But, there are other non-heroic (or at least ambiguous) female characters in horror stories. And, just like their male counterparts, these are often the baddies we love to hate. What (if anything) can viewing these people through an evolutionary lens bring into focus? I will argue quite a lot.

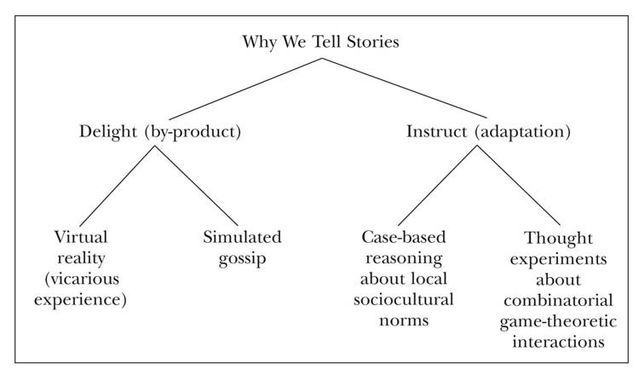

I’m neutral about the evolutionary role of stories. They may be a sort-of brain candy, intellectual cheesecake, but I’m open to the idea that they carry a surprising amount of information to transmit down the millennia. There are four main hypotheses:

There’s no doubt that we delight in story-telling and delight is often (not always) a clue that evolution has a dirty job for us to do, and needs us to be motivated to do it. When we find a baby cute, a lover beautiful, a cake delicious; it’s because the alternative is to find them smelly, annoying, or disgusting and our genes don’t want that. So they make the job fun.

Life is not a smooth transition from birth to death. It is marked by certain key transition points such as puberty, pairing up, childbirth, and old age. It is at these key choke points that organisms have to make decisions, both physiological and behavioral, that will maximize their chances of winning the game of life. And I am going to suggest that these patterns have seeped their way into our stories.

I once worked for a boss (not my current one I hasten to add) who said in a meeting about resource allocation, “Why can’t we focus our attention everywhere”. We all had a good laugh, then realized that he was being serious. We still had a good laugh, but later at his expense, rather than openly, in front of him. Of course, nothing and no-one can “focus its energies” everywhere. That’s what “focus” means. It means to concentrate on that which is vital. The downside of such focus is possibly missing other things going on, but that’s the trade-off. Life is full of trade-offs. Our dexterous hands can make tools, whereas our close relatives the chimps can crush skulls with theirs, but very little DNA separates us. Trade-offs can occur at a lot of different levels.

Life history theory is the biological modeling of how organisms allocate resources according to the slings and arrows (and also cakes and ale) of outrageous fortune. And, like my dim-witted ex-boss failed to realize, you cannot focus these energies everywhere. You need to apply your reproductive decisions in ways, and most crucially at times, when they will have the most impact.

What are these key stages? When it comes to women they are the four “M”s; menarche, mate selection, motherhood, and menopause. Each of these stages has horror characters whom we all know and love (or hate, or love to hate) who embody the trade-offs and symbolisms central to these stages. I don’t think this is a coincidence. But, before I try to make a believer of you, a few words about the “evil” in these characters. Isn’t a word like that a bit, well, biblical for a scientist? Not at all. From a biological perspective “evil” is at least this: “[The infliction of] massive evolutionary fitness costs on us, our families, or our allies.” (Duntley & Buss, 2006). Most of us have had at least some experience with having costs imposed on us, and imposing costs on others. I think this is why some of the characters I’m going to highlight are morally ambiguous. We do not just like bad boys—quite often we are drawn to bad girls as well.

Menarche

This is the stage of transition to fertility, characterized by bleeding, which is often marked by significant ritual activities across time and space. This transition can be accompanied by some pretty major transitions in terms of emotions and behavior as well. One of the core myths in our culture (we call them fairy tales sometimes) is Little Red Riding Hood (who is many millennia old), and it hardly strains the imagination to see the blood imagery and the barely coded warnings about sexually predatory males. Little Red Riding Hood with her themes of blood red, emotional turmoil, and nascent (but not fulfilled) sexuality is kin to Carrie, Regan in the Exorcist, Sadako (the Ring) and Aurora.

Mate Selection

As we get older we pair off. Well, sometimes we don’t and the role of the mate poacher exists in horror fiction across time and space. Using sex as a weapon, exploiting male weakness, and tearing up families. Examples of such figures in film and theatre include Alex Forest (Fatal Attraction); Carmilla (The First Vampire in Fiction); The Greek Bacchae, Salome’s Mother (Matthew 27:56); and the Jackal (G!kno//amdima’s sister in African mythology).

Motherhood

Motherhood is a period of unalloyed joy and fulfillment. Except when it isn’t. I’ve been reliably informed that the first forty years are the worst but even leaving that aside, there are trade-offs to be made. Humans are obligate investors and human babies require a lot of investment. This can lead to three possible dark sides, all well-represented in the horror genre

Protection of offspring.

Everyone knows not to get between a mother bear and her cub. Humans have a similar dark side—represented in the horror genre as being vengeful beyond all reason in the defense of offspring. From the monstrous mother in Beowulf; through to Annie Wilkes in Misery (yes, she sees Misery in maternal terms); and on to the Matriarch in the Aliens series, monstrous mothers are some of the more terrifying horror tropes.

Defection

An abiding fear that mothers might have is the feeling that the pregnancy is going wrong. A whole genre of horror stories from Medea, through Veronica Quaife in the Fly, Katherine (Damien’s mother) in the Omen; or Charlotte Gainsborough in Anti-Christ all explore themes of possession and the potential for the abandonment of a monstrous child. Which connects to the last sub-type:

Devil Children.

Fear of post-partum depression (and the possibility of abandonment) given real and horrible form. Chucky in the eponymous films, Rosemary’s Baby; The Babadook..dook…dook.

Menopause

Last but not least. Menopause is the transition to non-reproduction, but that does not mean that grandmothers no longer play a role. Far from it. We have good evidence that grandmothers contribute significantly to their great-grandchildren. So what could possibly be horrifying about that? To be blunt: Other people’s grandchildren (who might be rivals for resources). Across time and space (cultural and physical) the figure of the witch who interferes (usually magically) in others reproduction is a standard figure. The White Witch of Narnia, the Greek Morai who need to be propitiated, Baroness Bomburst in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (not a horror story, you say? The child catcher still scares me) are all good examples embodying symbols of sterility, magical interference and the hatred of others children.

I hope I’ve at least convinced you that female characters in horror stories are not merely helpless victims, but active (and sometimes scary) strategists with their own goals, methods, and desires. I think an evolutionary lens adds depth to their character but, whether you agree with me on that or not—Happy Halloween!

References

Duntley, J. D., & Buss, D. M. (2004). The evolution of evil. The social psychology of good and evil, 102-123.

King (2015). Regiments of Monstrous Women: Horror stories as a window into human life history. Evolutionary Behavioral Science.

Biesele, M. (1993). Women like meat: the folklore and foraging ideology of the Kalahari Ju/'hoan (p. 202). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Lewis-Williams, J. D. (1981). Believing and seeing: symbolic meanings in southern San rock paintings (pp. 3-14). London: Academic Press.

Clover, C. J. (2015). Men, women, and chain saws: Gender in the modern horror film. Princeton University Press.

Source: Jonathan Gotschall (with permission)