Shyness

The New Shyness

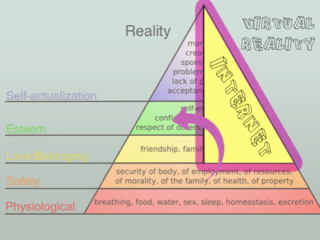

How virtual reality has made social isolation more seductive than ever before

Posted March 31, 2016

Growing up in the Bronx you have to have a thick skin. This made it difficult for my younger brother George, who was shy.

George was so shy that he used to wear a paper bag on his head to class. He wanted to connect with the other kids, he just didn’t know how. Hiding his face actually made him feel more comfortable in his environment.

He was what is known as dispositionally shy. Dispositional shyness implies a fear of rejection by being socially unacceptable to certain social groups or individuals, such as one’s peer group, authorities, or those a person wants to impress, such as members of the opposite sex.

In the last several decades shyness has evolved. Shyness now plays a key role in the complex causal cycle between the self-imposed social isolation of many young people and their excessive time spent in virtual worlds such as video games and porn.

In the 1970s and 1980s when I pioneered the scientific study of shyness among adolescents and adults, about 40 percent of the US population rated themselves as currently shy people, or dispositionally shy.

An equal percentage reported that they had been shy in the past but had overcome its negative impact. Fifteen percent more said that their shyness was situationally induced, such as on blind dates or having to perform in public. So only 5 percent or so were true-blue never-ever shy.

Over the past thirty years, however, that percentage has increased. In a 2007 survey of students by the Shyness Research Institute at Indiana University Southeast, 84 percent of participants said they were shy at some point in their life, 43 percent said they were presently shy, and just 1 percent said they had never been shy. Two-thirds of those who were currently shy said that their shyness was a personal problem!

The deep fear of social rejection has risen in part as a result of technology, which minimizes direct, face-to-face social interaction such as conversing with other people, seeking information, shopping, going to the bank, getting library books, and much more.

The net does it all for us faster, more accurately and without any need for making social connections. In one sense, online communication enables the very shy to make easier contact with others in the realm of asynchronistic communication.

But I believe it then makes it more difficult to make real-life connections, fueling a cycle of social isolation. As one of the researchers of the 2007 study, Bernardo Carducci, noted:

...changes in technology are affecting the nature of interpersonal communication so that we are experiencing more structured electronic interactions and less spontaneous social interactions where there is the opportunity to develop and practice interpersonal skills, such as negotiating, making conversation, reading body language and facial cues, which are important for making new friends and fostering more intimate relationships.

The new breed of shyness then arises not from wanting to reach out but fearing social rejection by making a poor impression, but, rather, not wanting to make social contact because of not knowing how to, and then further distancing oneself from others the more out of practice one gets.

Thus, this new shyness gets continually reinforced, internalized, and, worse, not even recognized when it leads to the absence of contact with most other people. And many shy people behave awkwardly or inappropriately with peers, superiors, in unfamiliar situations, and in one-on-one opposite-sex interactions.

So aside from the increase in shyness, what is different today is that shyness among young people, especially young men, is less about a fear of rejection and more about fundamental social awkwardness – not knowing what to do, when, where or how.

Most young men used to know how to dance and were able to engage young women in neutral topics of conversation. Now they don’t even know where to look for common ground, and they wander about the social landscape like tourists in a foreign land unable and unwilling to ask for directions.

Many of them don’t know the language of face contact, the non-verbal and verbal set of rules that enable a person to comfortably talk with and listen to somebody else and get them to respond back in kind.

The absence of such critical social skills, essential to navigating intimate social situations, encourages a strategy of retreat, going fail-safe. Girls and women equal likely failure; safe equals the retreat into online and fantasy worlds that, with regular practice, become ever more familiar, predictable and, in the case of video games, more controllable.

A twisted sort of shyness has evolved as the digital self becomes less and less like the real-life operator. The ego is the playmaker; the character is the observer, as the external world shrinks to the size of a young man’s bedroom. Hence the worldwide phenomenon of hikikomoris, NEETs, Bamboccionis, etc.

In this way, we can say that shyness is both a cause of the problem as well as one of the consequences of excessive gaming and porn use. As one young man from our survey for Man, Interrupted commented:

I play video games and watch pornography on a regular basis… but I’ve always been average looking and I’ve hated the tiresome aspect of having to make the effort to appease the opposite sex. It’s expensive, confusing and rarely successful. I feel like the personal relationships with any girl/woman I’ve known have meant nothing to me and can be easily substituted with male company whilst pornography fills the rest.

To tackle this new shyness, we must re-engage young men by challenging them and rewarding them in ways they need to be in the real world.

Over the last few decades society has focused on boosting girls and women, which has been much needed. But during this time, boys’ needs have been largely neglected. Nobody has seen investing in their development as “worth it” – now many of them don’t see investing their time back into the real world as worth it.

Society must show young men that they are lovable and desirable – essentially show them they are worthwhile human beings – if we wish to see them RE-connect, rather than DIS-connect, with society at large.