Child Development

Has Callout Culture Finally Gone Too Far?

The Twittersphere reacts to Heisman Winner Kyler Murray's old tweets.

Posted December 9, 2018

Hours after Kyler Murray was awarded the coveted Heisman Trophy, old tweets surfaced in which he used the term “queer” to refer to some of his friends. News outlets quickly reported that he had used “an anti-gay slur in a tweet to friends,” or more accusingly as “using an anti-gay slur to defame them,” with headlines that invariably called the tweets “homophobic.” Some referred to other well-known personalities who have been publicly shamed as a result of old tweets.

We once viewed childhood as a time for kids to learn how to be a person in the world. But over the past few years, a different way of thinking about childhood—and human nature—has emerged. The witch hunts of Salem may have stemmed from a view of human nature that assumed all people are born either good or evil. In callout culture, witch hunts are back, and it seems as though this view of human nature is, too.

In some ways, freshmen arriving on residential college campuses face much higher expectations of their maturity than their parents did when they arrived, even though this generation of students have met far fewer critical milestones on the road to adulthood than had their parents at the same age. At a time when many students begin college already contending with anxiety and depression, these expectations certainly don’t help.

Imagine what it must be like to embark on students' first extended experience away from home and parents, and be confronted with an ideological orthodoxy to which they must subscribe—or be labeled (in one or more ways) a Very Bad Person. This fundamentally religious view of human nature means students are not only expected to conform, but also to have already learned everything there is to know about how to be a person in the world before they arrive.

What was once considered thoughtless or insensitive is now called “aggressive” (albeit “micro”), and instead of a college education including an understanding that everyone will learn from each other, nonconforming students are silenced with an injunction to “educate yourself!” Engaging in dialogue with other students who don't have the same perspectives is no longer a common expectation on campus. Instead, this is seen as oppressive “emotional labor.”

Young people can be morally indicted not just for what they say, but for anything they once wrote to someone in an email or posted on social media. And worse, the messy, ugly parts of this generation’s childhood will live on forever, etched in cyberstone, able to be recalled with only a few taps and swipes. Young adults can now be condemned for words their 9th-grade selves used—as if by the time they enter high school, children should all be mature enough to know better.

In a swift online apology, Murray noted that his tweets were issued when he was 14 and 15. “I used a poor choice of word that doesn’t reflect who I am or what I believe. I did not intend to single out any individual or group,” he wrote.

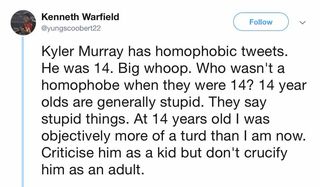

Refreshingly, the Twittersphere appears to have come to his defense. One follower succinctly reminded us that our childhood selves are not our best selves: “14-year-olds are generally stupid. They say stupid things. At 14 years old I was objectively more of a turd than I am now.” Another noted, “You were still going through puberty at the time of the tweet. The media, however, is still as childish as ever.” Many others, whether football fans or not, are posting similar sentiments.

This online reaction is encouraging. Maybe callout culture has finally gone too far, and we're at a turning point. Perhaps it's time for us to be more charitable about one another's less than perfect past. ♦

Pamela Paresky's opinions are her own and should not be considered official positions of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education or any other organization with which she is affiliated.