Relationships

The Photographer Who Taught Us to See the Unseen

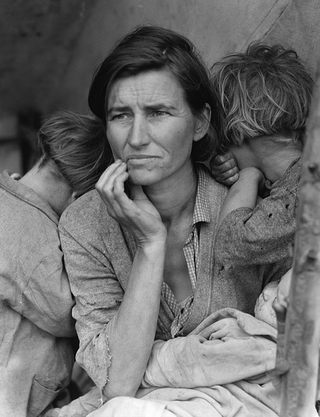

Dorothea Lange opened our eyes to the plight of the poor.

Posted January 21, 2020

Dorothea Lange was one of the 20th century’s great American photographers and created perhaps its most iconic image: “Migrant Mother.” Her images of the impoverished, hungry, and incarcerated may have done more than the words of any journalist or politician to foster public sympathy for their plight, in part because she had been there herself.

Born in New Jersey in 1895, when Lange was 7 years old she contracted polio. She became known as “Limpy,” later saying that the disease “guided me, instructed me, helped me, and humiliated me.” When Lange was 12, her family was evicted from their home. Her father vanished, and her mother, she, and her younger brother were forced to take lodging with her grandmother.

A desultory student, Lange managed to graduate from high school. When her mother asked her what she wanted to do next, she replied that she wanted to be a photographer. Eventually, she enrolled in a photography class at Columbia. Later, she and a friend embarked on a round-the-world voyage but only got as far as San Francisco before their money was stolen.

There she opened her own studio, which attracted wealthy patrons. She traveled to Arizona, where for the first time she saw and photographed “Indians, Mexicans, and poor whites.”

Back in San Francisco during the Great Depression, she became more and more acutely aware of the poor and unemployed all around her. She took her camera and headed for the slums.

Lange soon met Paul Taylor, an economist who studied the plight of migrant farmworkers. It was at a migrant camp in 1936 that Lange took her most famous photograph, “Migrant Mother.” Taylor urged the government to improve migrant living conditions, but farmers and townspeople resisted such improvements.

In 1941, Lange received a Guggenheim Fellowship, the first awarded to a woman in photography. A year later, President Roosevelt signed an order establishing concentration camps for Japanese Americans. Relinquishing her fellowship, Lange worked for the War Relocation Authority, documenting the internment. During the war, the Army impounded most of her images.

After the war, Lange received numerous commissions from “Life” magazine, and her work was displayed at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Her health declined through most of the 1950s and 60s, and she died of esophageal cancer in 1965.

Lange’s most famous photo depicts a family’s humble living space. At the center of the image is the mother. Her hand is drawn up to her mouth, and her expression is one of evident concern. She holds a baby in her arms. She is flanked by two daughters, both of whom are turned away from the camera.

We get the sense that only the mother can look at the misery that lies before them, a sight the children cannot ever bear to behold. In an irony even Lange might have found troubling, after she captured the photo, she went on to become a famous photographer, never to see or interact again with the subject of her most famous work.

Lange focused her lens on ordinary people and especially the poor. In photographing them, she used the same techniques of composition that she had perfected with San Francisco’s elite, imbuing their lives with significance. Those who had witnessed the intimacy of her images would find it more difficult to dismiss the nameless and property-less as “the poor.”

As she would write years later, “The camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera.” Through her lens, she could teach viewers what is worth noticing and how to look. And she could engage not only our eyes but also our hearts and eventually our minds and hands, summoning us to reach out to those in need.