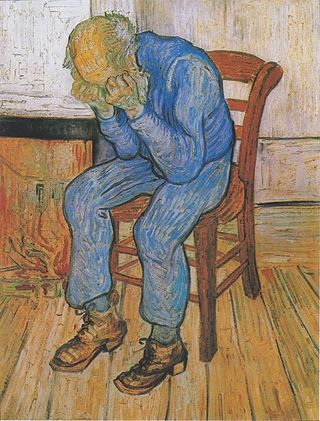

Depression

Beyond MDD: Understanding the Types of Depression

Depression is a heterogeneous condition with varied symptoms and causes.

Posted October 5, 2019 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Depression is a serious and complex human condition that has afflicted mankind for millennia. Attempts to define and treat depressive illnesses are as old as the field of medicine itself and predate the founding of modern scientific psychiatry in the 1800s. The current psychiatric classification system, the DSM-5, includes a single diagnosis for depression: major depressive disorder (MDD).

Yet the idea that all depressions represent the same form of psychopathology, i.e., MDD, is a relatively new concept in psychiatric theory. For much of the 20th century, depression was conceptualized as a heterogeneous condition consisting of various types, believed to have different underlying causes and to be treated accordingly. Distinguishing depression on the basis of its cause was widely believed to be of chief importance in determining the best course of treatment.

Below, I outline some of the types of depression, which I believe remain relevant to clinical practice despite their omission from the modern DSM system.

Endogenous Depression

Endogenous depressions are depressions that occur in the absence of any known psychological or social stressors. Also termed "metabolic depressions" or "biological depressions," these depressions seem to "come out of the blue" and are characteristically cyclical in their nature. Patients with endogenous depressions are unable to identify any trigger for their depression and often have a family history of mood disorder or suicide.

Because the cause of endogenous depression is believed to be biological, antidepressant medication is used as a first-line treatment, often in combination with psychotherapy. For treatment-resistant cases, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) may be necessary to relieve acute suffering. This type of depression aligns closely with the classic psychiatric concept of melancholia.

Exogenous Depression

These depressions are also termed "reactive depressions" or "situational depressions" and are caused by some external factor—most commonly, in the psychoanalytic theory, the loss of a loved person or object. The onset of an exogenous depression may be triggered by any of a host of adverse life events, including the death of a family member, the loss of a job, financial strain, medical illness, etc. The patient with an exogenous depression is almost always able to identify the reason or reasons they have become depressed, and the onset of the depression coincides neatly with the environmental situation or trigger. Because these depressions are deemed to have a psychological cause, psychotherapy is the treatment of choice.

I have written elsewhere on the distinction between endogenous and exogenous depression (see "Revisiting the Concept of Reactive Depression") and have noted some important limitations to this type of conceptual distinction. First, it could be true for some patients that adverse life events are merely coincidental, and the person would have become depressed regardless of any external events. Also, it is true logically that no depression exists independent of one's neurobiology and neurochemistry.

It could also be the case that the external events merely trigger an underlying physiological depression. Conversely, it is possible that an apparent endogenous depression is caused by psychological factors outside of the patient's conscious awareness.

Anaclitic Depression

This form of depression, conceptualized as resulting from an infant's physical or emotional separation from its mother, is characterized by intense fears of abandonment and feelings of hopelessness and weakness. This leads the patient to place an inordinate value on relationships over personal autonomy and leaves the person vulnerable to depressions in response to the loss of a relationship or interpersonal conflict (American Psychological Association, n.d.). Object relations theory has contributed vastly to the understanding of anaclitic depression, and its treatment should include psychoanalytic psychotherapy or psychoanalysis.

Introjective Depression

An introjective depression is a highly self-critical depression. The American Psychological Association (n.d.) defines it as follows:

"Intense sadness and dysphoria involving punitive, relentless feelings of self-doubt, self-criticism, and self-loathing. The individual with introjective depression becomes involved in numerous activities in an attempt to compensate for his or her excessively high standards, constant drive to perform and achieve, and feelings of guilt and shame over not having lived up to expectations."

The believed cause is an early environment characterized by hostile criticism and unattainable expectations.

Depressive Personality

The psychiatrist Kurt Schneider, best known for his first-rank criteria for schizophrenia, introduced the concept of depressive or melancholic personality in the 1950s, and the construct was included in the DSM-IV as a condition for further study.

Those with a depressive personality seem to have a usual mood dominated by gloominess, cheerlessness, and joylessness, and are often brooding, negativistic, and critical of others. They tend to be pessimistic in their general outlook on life. Whereas major depression is an episodic condition, depressive personality represents a persistent disturbance in mood. In this sense, it is similar to dysthymia, or persistent depressive disorder.

Dysthymic Depression

Unlike the other types of depression listed above, this form of depression is afforded its own diagnostic entry in the DSM-5: dysthymia or persistent depressive disorder. Dysthymic depression is a chronic, low-grade depression that consists of milder symptoms for a prolonged period of time. It is virtually indistinguishable from depressive personality, and many psychoanalytically-inclined practitioners prefer to conceptualize this type of depression through the lens of personality disorder. In some cases, dysthymia is more difficult to treat than major depression.

Atypical Depression

Atypical depression is a depression characterized by an improved mood in response to positive life events. In contrast, patients with melancholic depression generally do not experience improvement in mood in response to normally pleasurable events.

Patients with atypical depression also evidence weight gain, increased appetite, and leaden paralysis (a heavy sensation in the limbs), all of which are uncommon in other forms of depression. The term "atypical" does not mean this type of depression is uncommon or unusual; rather, it was chosen because atypical depressions seem to respond differently to medications than melancholic and other forms of depression.

Bipolar Depression

Bipolar depressions are depressions that alternate with periods of euphoria, elation, and high energy and constitute one phase of a bipolar or manic-depressive mood disorder. Bipolar disorder can be classified as either bipolar I disorder, characterized by full-blown manic highs, or bipolar II disorder, defined by less intense hypomanic episodes. Both forms of illness almost always include a depressive phase. Treatment of bipolar disorder includes lithium carbonate or other mood-stabilizing medication, sometimes in combination with antidepressant medication.

Conclusion

Depression is a complex condition that may, in fact, represent numerous psychopathological entities. This is not meant to be an exhaustive list of the subtypes of depression, nor should it be taken as medical or psychological advice. While the DSM neatly classifies all unipolar depressions as major depressive disorder, other types of depression appear in the professional literature and may constitute unique psychiatric disorders.

Facebook/LinkedIn image: Sam Wordley/Shutterstock

References

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). APA dictionary of psychology. Retrieved from https://dictionary.apa.org/