Education

To Learn Better, Make Mistakes

New findings suggest deliberately making and correcting errors boosts learning.

Posted March 26, 2022 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- Many effective learning strategies, such as concept-mapping, discourage errors.

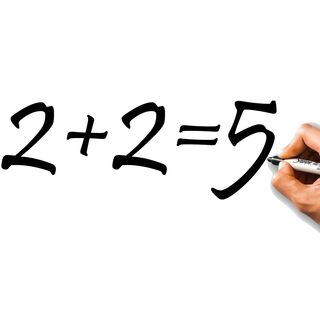

- New research shows that intentionally making mistakes and correcting them can enhance learning. This is called the "derring effect."

- Learners who have experienced the derring effect often remain unaware of its cognitive benefits and positive impact on test performance.

Suppose you are studying for a test and, despite knowing the right answer, deliberately make a mistake and subsequently correct it? Might this unusual technique, known as the "derring effect," help you learn the material more effectively?

Yes, according to recent research by Wong and Lim, published in the Journal of Educational Psychology. The investigation’s methods and findings are discussed below.

Deliberate Errors and Meaningful Learning

Experiment 1

Between-Subjects Design

Sample: 120 English-speaking college students (87 females); the average age of 20 years old.

Procedure: Participants were instructed to study a text. They were told they would be tested on it.

There were three conditions: copy, concept-map, and concept-error.

And there were three stages to the experiment, as described below:

Practice stage: Individuals in the copy condition were asked to copy the practice text and underline key concepts. Those in the concept-map condition were asked to create a concept map depicting the relationship between concepts visually, using nodes and arrows.

Students in the concept-error condition were instructed to write down every sentence “such that it contained a plausible conceptual error (i.e., an error in understanding or interpreting a concept), before striking out this error and correcting it by writing down the actual concept exactly as it was presented in the text.” To illustrate, for “Bats are mammals that fly,” an acceptable response would be, “Bats are birds (mammals) that fly.”

Study stage: Participants were instructed to read and study a text (either on food allergies or volcanoes) using the method assigned (copy, concept-map, or concept-error learning strategy).

This was followed by answering questions about their familiarity with the subject matter, understanding of the material, and predicting how well they had learned the information (i.e., “judgment of learning” or JOL).

Test stage: In the application test, participants were presented with a news article related to the topic of study (i.e., food allergies or volcanoes) and asked to answer a few questions.

In the free recall test, they were required to write down everything they could recall from the studied material.

Last, they rated the effectiveness of the learning method assigned.

Results: Relative to the learning strategy of copying or concept mapping, the learning technique of deliberately making and correcting mistakes “produced superior recall performance and...enhanced students’ meaningful learning in applying their knowledge to analyze a novel news event.”

So, the findings “provide evidence for the derring effect in both knowledge retention and higher-order application.”

Surprisingly, the data also showed students were largely unaware of the benefits of deliberate erring (i.e., concept-error technique).

Experiment 2

Within-Subjects Design

Sample: 40 English-speaking college students (32 females); an average age of 21.

Procedure: This was a replication of the first investigation and had three phases: practice, study, and test.

There were only two conditions; concept-error and concept-synonym. All participants experienced both conditions (i.e., studied both texts), so there were four tests—two free recall and application tests.

The concept-error learning strategy has already been described (see Experiment 1). But the concept-synonym learning strategy is new: In this condition, participants were required to elaborate on a text they were given by “writing down each sentence such that it contained a conceptual synonym (i.e., an alternative word or phrase with the same meaning as the actual concept), before underlining this synonym,” and copying the concept just as it was in the text.

We can think of the concept-synonym learning technique as a type of paraphrasing, of writing things in one’s own words.

To illustrate the difference between concept-error and concept-synonym, consider the statement, “Magmas that are low in silica tend to be very fluid.” Here are sample responses for each condition:

- Concept-synonym. “Magmas that are low in silica tend to flow very easily like liquid (be very fluid).”

- Concept-error. “Magmas low in silica tend to be very

viscous(fluid).”

[Note: The italicized segment represents the text that would be underlined.]

The researchers’ goal in comparing these two conditions was to determine whether the benefits of intentional erring were related to the active generation of correct elaboration of the material (i.e., concept-synonym) or incorrect elaborations (i.e., concept-error).

Results: Analysis of data showed that “Deliberately committing and correcting errors produced superior retention and higher-order application performance even over generating conceptual synonyms.”

And since both learning techniques entail coming up with elaborations, elaborations alone cannot explain why the derring effect occurs. So, the benefits of the derring technique must be “specific to having first deliberately produced an incorrect response.”

Another finding was that participants were unaware of the benefits of the concept-error technique (i.e., of deliberate erring). They wrongly predicted that the concept-synonym learning strategy would be equally or more effective than the concept-error learning strategy, “even after their actual test performance revealed otherwise.”

Takeaway

Over the years, research has explored a variety of very different approaches to improving memory and cognition, some of which have shown promising results—e.g., mindfulness meditation, moderate-intensity exercise, even chewing gum.

So, just because some behavior appears unrelated to cognitive functioning, it does not mean it is necessarily ineffective in boosting learning. The same is true of unusual learning strategies.

The research reviewed here shows concept-error learning (intentionally making mistakes and correcting them) can improve meaningful learning, memory, and test performance.

To use this study technique yourself, write down wrong responses to the questions and correct them. But make sure the wrong responses you generate are conceptually believable, meaning that they are errors in understanding or interpretation, as opposed to spelling mistakes.

For instance, it is a more believable conceptual error to consider apples to be vegetables than animals.

Try this study technique and compare it with others you know. Here is one approach: Apply the concept-error learning method for one chapter and your usual learning method for another chapter. Then compare the results. You may be surprised.