Self-Control

What Parents Need to Know About Kids' Meltdowns

Brain-education and strategies to deal with meltdowns in kids and teens.

Posted July 31, 2020 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Tantrums, meltdowns, and stormy behavior are common among toddlers between ages 2 and 4. If parents and caregivers have a good understanding of brain development, we are better positioned to respond constructively to tantrum and meltdowns of toddlers, kids, and teenagers.

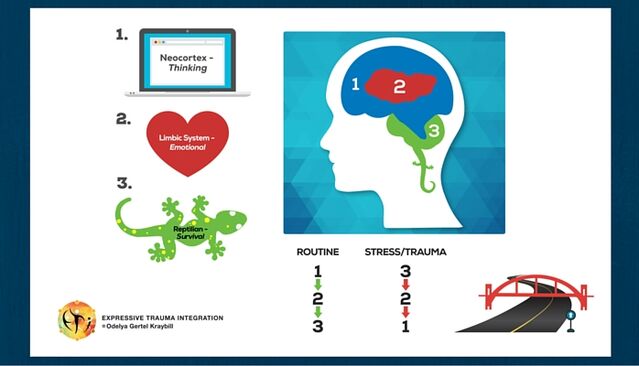

The brain develops from the bottom upward. Lower parts of the brain, the reptilian and limbic systems, are responsible for ensuring survival and are activated in moments of high stress. The upper part of the brain, the neocortex, which develops from about 4 to 6 years of age, is responsible for executive functions like making sense of what we are experiencing, applying reasoning and moral judgment, and making choices.

The development of the upper brain depends upon prior development of lower parts. The brain is meant to develop like a ladder, from the bottom up. So if an infant or toddler experiences high distress frequently over an extended period of time, sequential development of the brain is disturbed. Physical growth of parts of the brain may be slowed down and related functions impaired. Eventually, the ladder develops, but the disturbance in the early formation of the brain can cause enduring problems.

One of the biggest problems is in re-establishing higher brain control after stormy moments. In the diagram below, the 1-2-3 sequence symbolizes how the brain should function in times of normality. The higher part of the brain is in control, not the reptilian brain. We want reason and choice-making to dominate, even when we are upset.

When we are extremely angry or afraid, the order reverses, to 3-2-1. Now the instinctive, quick-acting reptilian brain is in charge. That’s appropriate sometimes, for certain situations. For example, the urgent instinct to flee from danger or resist an attacker might be a lifesaver.

We live our lives in the interplay between these two powerful brain modalities and one of the biggest developmental challenges we face growing up is managing their interaction.

Adults take it for granted that young children are not yet able to control their responses in moments of anger or fear. We soothe them or, if they are angry, we tolerate their outrage until they are calm. In other words, we tolerate the behavior of small children when their lower brain is in control; we do not expect them to quickly regain upper brain control.

As children get older, our expectations change. We calm and soothe them, but we expect growing self-restraint and the ability to reason. We want them to mature into adults who self-regulate anger and fear responsibly. With each passing year, we expect a higher level of performance in this.

For children who experienced a disturbance in early brain formation, this rising expectation is extremely difficult. The self-regulation we expect of them requires the brain to transition during moments of upset from lower brain control to upper brain control. But they are shaky in managing this difficult task.

This includes children and teens with a variety of diagnoses such as Sensory Processing Disorders (SPD), Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), anxiety, depression, conduct disorder, and Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD), etc.

For such children, the reptilian part of the brain is unusually sensitive and reactive. Once triggered, it persists in staying in control of brain functions longer than it should. This means that tantrums, meltdowns, or high anxiety are more easily set off and last longer than they otherwise might. They are in 3-2-1 mode much of the time, in a world expecting them to be in 1-2-3 mode.

Children who are impacted in the way described above are not well-suited to treatment approaches that rely solely on cognitive or behavioral methods as a first line of intervention. These methods engage the upper part of the brain and assume they are able to engage with it enough to be able to execute cognitive processing and behavioral changes. But for children of almost any age, when meltdowns, tantrums, and stormy ups and downs are a prominent part of life, this is not yet the case.

Instead, we need to intervene with strategies for calming a child’s nervous system and building an interpersonal connection with the child in ways that are compatible with the lower parts of the brain. Once that is established, we can proceed to re-engage the upper brain and strengthen its functioning, and cognitive and behavioral methods have a useful role to play in this.

The first step is attunement—a process that most parents do naturally with their children when they are small and which, with effort and skill, caregivers and therapists can replicate as well. Although attunement may seem simple and completely ordinary—which it is for adults who received stable attunement when they were small—it is in fact a complex process with big implications that will unfold over a lifetime. Without it, orderly brain development will be impacted.

Attunement and How to Give It

Attunement is a nonverbal process of being with another person in a way that attends fully and responsively to that person. A key aspect of attunement is that it is a joint activity, experienced in interactions with a caregiver.

In childhood, parents are never able to anticipate and meet all of a child’s needs. So it is unavoidable that an infant will get upset from time to time. Schore and Shore (2008) call this “misattunement.”

Well-functioning parents respond appropriately to soothe the baby, which Schore calls “reattunement” (2008). Through repeated cycles of attunement, misattunement, and reattunement, an infant acquires experience in managing the gap between their own senses and needs on one hand and what the external world delivers to them on the other.

At birth, a baby is fully dependent on parents to facilitate moving through the cycle and return to reattunement. But over time, babies internalize the process. They become more able to manage moments of frustration and more able to achieve reattunement. From this emerges a sense of self and ability to control emotions or emotional regulation.

So far I’ve described early life experience. But because attunement is key in the development of emotional functioning, we can use it in working with certain children of any age as well as young adults with neuropsychiatric symptoms.

In stormy moments, they too are reactive (3-2-1) and unable to deploy the resources of the upper brain to control their emotions. In such moments, for them, as for infants, consequences and other cognitive responses may have a little helpful impact.

In fact, consequences may lead to a greater sense of shame and guilt and feelings of being out-of-control, or worthlessness that was already there due to the ongoing difficulty with meeting expectations for self-regulation.

This does not rule out consequences and other cognitive responses designed to impact how a child or young person makes choices. The point is rather that we must be careful about when and how to use such responses. They are most useful when there are signs that a child has returned to some level of rational functioning and it is able to engage with reasoning.

Responding to Meltdowns

-

Remind yourself that this is a 3-2-1 moment, and reasoning probably won’t work.

-

Remind yourself that storms are cyclic. They have phases of intensification and de-intensification, and cyclic events always end.

- Stay present as much as you can until it passes. It is very difficult to be present when your child is “out of control." However, it is critical to do so, for children in these moments soon begin to think of themselves as destructive and not worthy ("I am bad"; "I can’t control it"; "I am worthless"). Give them a sense that they are not alone in this and that, no matter what, you are sticking by them. Stay physically visible so your child can see you, and if they will allow you, try to soothe them. If they don’t accept soothing, just hang around calmly in the vicinity.

- Reduce expectations from your child.

- Reduce expectations of yourself. Just getting through this moment without becoming emotionally reactive yourself is a huge accomplishment. Set aside thoughts of "teaching a lesson" or announcing establishing new rules or principles. There’s time for that later when you and the child are calm if you still think those thoughts are wise.

- Avoid bribes (especially not candy and numbing tactics). Bribes may help immediately but in the long run, will create an unhelpful mechanism in the child that seeks to replace any intolerable experience with instant gratification and/or quick numbing tactics.

- Wait for the cycle to pass and reattune. Reattunement, in this case, can be giving them a hug, telling them that they are loved also when they are stormy, that everyone gets stormy sometimes (examples of your own experience are always best), that together you will find the best possible ways to help them feel better.

If you do become reactive to your child, simply follow the reattunement model. First, reattune within yourself. Then reattune with your child. Going through cycles of misattunement that then lead to reattunement is how children learn reattunement. So do not be too distressed about misattunement. Just focus on assisting reattunement as soon as you are able. Through many repeated experiences of this, your child will eventually learn to model your responses.

- Notice and remember the good times. Write them down and remind yourself and your child of them later. In calm times, remind them (and yourself) that good moments are also a part of life. Take this time to make the first steps to learn and facilitate self-compassion. Read more in this post.

- Reset. Some children, especially the young ones, may be able to engage in the Reset Exercise* and divert the storm. This exercise resets the nervous system and helps get back to upper brain functioning.

- Psychoeducate your child, other caregivers, and family members about the brain, explaining the difference between 1-2-3 mode and 3-2-1 mode. Use this information in times of calm and create together a response plan for stormy times. Having a plan is no guarantee it will always work. But even when it does not, it helps a child who is out-of-control to recognize the episode does not mean they are bad or destructive, rather they are suffering from an over-active biological response whose overall purpose is to help them stay alive. More in this post.

- Get help and learn how to help your child self-regulate. Self-regulation is the ability to manage extreme (positive or negative) emotions, sensations, and thoughts. Learning to self-regulate is essential to maintain 1-2-3 modes of response. Read more in this post.

- Rule-out and treat underlying root-causes that lead to neuropsychiatric symptoms. For toddlers, kids, and young adults who suffer from SPD, OCD, ODD, ASD, ADHD, Conduct Disorder, DMDD, Eating-Disorder and Body Dysmorphia, Self-Harm, Major Depression, Bi-Polarity, PTSD, cognitive impairment, speech delay, learning disabilities, and more, first rule-out medical root causes such as inflammation and underlying infections. Before choosing mental health interventions, get informed about underlying infections as root causes for neuropsychiatric symptoms. More in this post.

- Work on developing a family sustainability plan. Dealing with kids'/teens' tantrums is draining and requires a systematic response that includes all family members. An individualized Sustainability Plan (ISP) is an integrative plan for self-care designed to assist the continuity of progress. It contains a variety of techniques and practices tailored to a client's unique situation and preferences and addresses all aspects of wellness, including emotional, cognitive, physical, spiritual, and social aspects. ISPs draw from various practices demonstrated to be effective in mitigating stress symptoms and enhancing the capacity to experience joy. Read more in this post.

*Reset Exercise:

Jump up and down (as fast as you can) 10 times.

Sit down (preferably leaning back on something) and breathe in (2-3-4). Hold (2-3-4-5) and breathe out. Make an s-s-s-s or hm-m-m-m sound on the out-breath and notice how the sound changes during the out-breath. Repeat the deep breathing part five more times.

References

Schore, J. R., & Schore, A. N. (2008). Modern attachment theory: The central role of affect regulation in development and treatment. Clinical Social Work Journal, 36(1), 9-20. Wylie, M. S., & Turner, L. (2011). The attuned therapist. Psychotherapy Networker, 35(2), 19-27.