Creativity

Your Brain on Creativity

Neuroscience research reveals creativity's "brainprint."

Posted February 22, 2018 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn't really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. That's because they were able to connect experiences they've had and synthesize new things. —Steve Jobs

Creativity is amazing. Play is amazing. Being original is amazing. Amazing, astounding, thrilling, asymptotic. Divergence opens up possibilities, creating the flexibility to be extraordinary, to stand out from the crowd and enliven others with a spellbinding display of wit and artistry. When attuned to the environment, when humor is working well and the timing is right, the ideas flow… with art which speaks to the zeitgeist, capturing the ineffable in an ineffable way… creativity leads to deep communion and empathy.

When out of step, the creative process can spiral into loneliness, even despair, leaving you feeling excommunicated and muted inside. The wise recognize, however, that being creative does not always go along with being playful. For many, creativity is serious business, and not at all playful. Like the tango, it takes two to play. In fact, if one person is playing and the other person is not playing, it isn't play — it is something nonconsensual, a non-starter at best which can verge into teasing and intrusion.

Systems in the Brain

What is happening in the brain during periods of heightened creativity? In their recently published paper "Robust Prediction of Individual Creative Ability from Brain Functional Connectivity," Beaty and colleagues (2018) unearth the neurological signature of creativity, using sophisticated approaches to identify the neural network activity, the "brainprint" as it were, which is associated with divergent thinking, and then using that understanding to distinguish more creative from less creative brain activity.

I like to call them the “Big Three” brain networks — the default mode network, the executive control network, and the salience network. Prior research suggests that they work together when it comes to being creative. The default mode network is what's happening in the brain in a resting (but not sleeping) state, the brain’s “idle state.” The executive control network monitors what is going on, manages emotional parts of the brain, directs resources like attention, and oversees decisions and choices. The salience network determines which sorts of things tend to be noticed, and which tend to fly under the radar. In PTSD, for example, the salience network is scanning for threats.

For creativity, scientists hypothesize that the Big Three operate as a team: the default mode network generates ideas, the executive control network evaluates them, and the salience network helps to identify which ideas get passed along to the executive control network. On top of this basic schema, these networks can also influence one another via other feedback loops. For instance, the executive control network might “tune” the way the salience network scans internally, depending on the task at hand, in response to the environment.

These brain networks form a somewhat flexible and responsive system, a "complex adaptive system." Not only is it a resilient learning system, but the brain has also evolved in relation to the environment. With human beings, it isn’t just the physical environment, it is the world of language, culture, and ideas. Of social relations. The level of entropy is much higher as a result of these social and cultural factors, because the information reflected back has so many more possible states it can be in. That’s entropy, a measure of the number of possible states a system can be in, and consciousness is very entropic.

Especially with creativity. Creativity is closely linked to what folks have called “divergent thinking.” Looking at divergent thinking tasks, compared to conventional tasks, and measuring brain activity is how the current research is set up. Beaty and colleagues look at basic brain activity with fMRI and use (similar to other work, such as using machine learning to predict suicidal intent, to understand the effect of cannabis on the brain, and to enhance psychiatric diagnosis) machine-learning approaches, and then leverage those computational models to predict which individuals from a group of people are more creative just by looking at their brain scan.

Even at this very early stage, the predictive ability is pretty impressive. Not quite ready for primetime, but it makes it easier to imagine a human resources evaluation involving analyzing functional neuroimaging during different task types. We can call it NeuroHR, following with the "NeuroEverything" trend. Way better than any tool used by HR nowadays, probably. Still science fiction, but becoming more real.

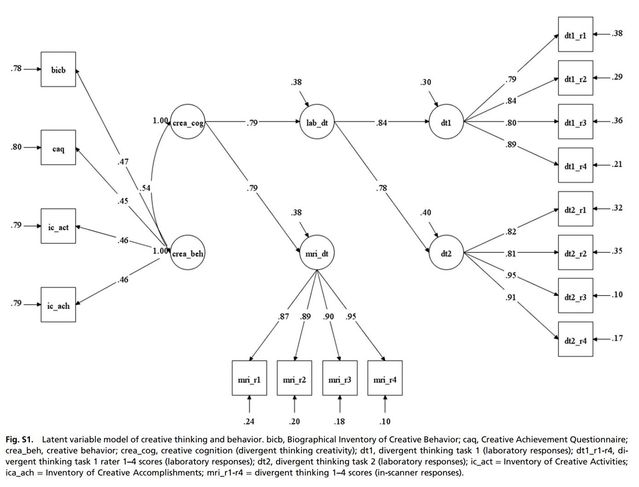

Your Brain on Creativity

The researchers scanned 163 Australian participants, having them perform two different cognitive tasks. The one measuring divergent thinking is called an “Alternative Use Task” (AUT), and the comparison non-creative task is an “Object Characteristics Task” (OCT), basically just describing something without embellishing at all. Not creative. People were rated on their answers when asked to come up with unusual uses for random objects, looking at uncommonness, remoteness, and cleverness to come up with an overall score on divergent thinking. They also completed a battery of questionnaires about their actual creativity: the Creative Achievement Questionnaire, the Biographical Inventory of Creative Behavior, and the Inventory of Creative Activities and Achievements.

Their findings were complex, covering correlations in the creativity questionnaires and, from a neuroscientific view, relating to several specific brain regions core to the Big Three brain networks, and included correlations among brain networks between the divergent thinking creativity task and the basic object description task.

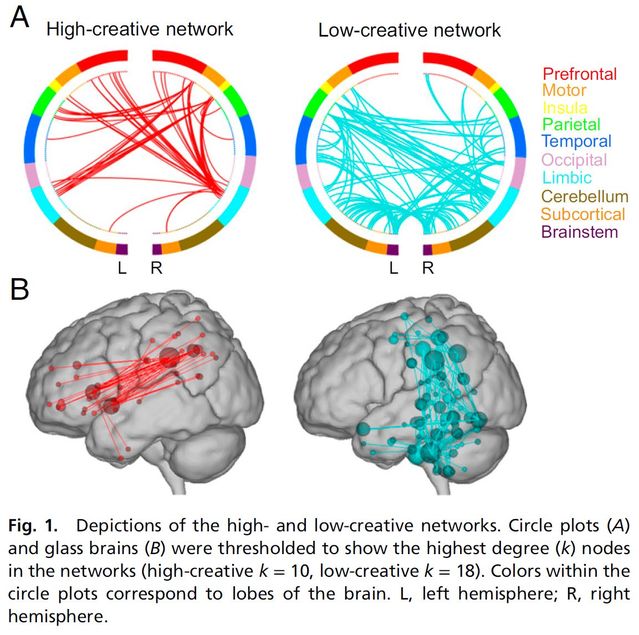

First, they found that self-reported measures of creativity correlated well with measured creativity performance, confirming the validity of self-report. Using a branch of mathematics called “graph theory” which is used in modeling neural networks, they identified the “hubs” or “nodes” through which the most information flowed during creativity tasks, and defined the connections between hubs (“edges”) to determine which were most important in distinguishing creative from baseline tasks.

Briefly, during the creativity condition, they found dense functional connections in the areas of the brain related to the three networks of interest, scattered through the frontal and parietal cortices. The areas identified are core hubs for the different networks, including, for example, the left posterior cingulate for default mode, left anterior insula for salience, and right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex for executive networks. The 25 most highly connected nodes during the creativity task included 12 from the default mode network, four from the salience network, and three from the executive control network.

For the low creativity task, there was some overlap with the default mode network, to be expected given that it is involved in standing brain activity, but the rest of the nodes were mainly located in subcortical, deeper areas of the brain in the brainstem, the thalamus and cerebellum, which are distinct from the cortical areas found in creative activity.

The correlations within creativity networks were strong, showing internal consistency; the correlations in the non-creative networks were also strong, and they were not correlated with one another, and each pattern of activity was unique to the task of interest. These last confirmatory steps were critical to making sure these findings could then be used to predict creativity for a different group of participants unrelated to the people studied to obtain the data in the first place. These findings confirm earlier studies on brain networks in creativity, replicating and extending our understanding of how the brain generates divergent thinking.

They showed that their findings could then be used to identify who is more and who is less creative, just by looking at brain scans of them doing nothing in particular. When they imaged this different group of 405 Chinese participants, they found that measured creativity scores (shown to be an accurate reflection of real-world creative performance in the first stage) were significant when correlated with resting-state MRI data. Note that the participants in the second phase of the study were not engaging in any tasks. Creativity was reflected in measuring their minds at rest. To make sure the predictive model was checking creativity and not overall intelligence, they checked and found that creativity network measures were not correlated with intelligence.

Futurism and Neuroscience

These results are of critical importance for anyone seeking to understand, and possibly enhance, creativity, for they point to the global nature of generative processes for engaging multiple brain networks, activating in sync, providing feedback to and mutually regulating one another. There isn't one "creativity" area in the brain; creativity emerges from the interplay of complex brain activity involving multiple more basic systems. The implications of this work, just in the early stages, are remarkable.

Would an approach like this be useful in identifying creativity for hiring purposes ("NeuroHR") or in evaluating applicants for an education involving creativity? Could this approach be used to track outcomes in training up creativity, or therapeutic outcomes, or to enhance problem-solving by increasing divergent thinking? Could neuroscience be used to help people with writer's block or artists who have hit a dry spell?

Change the Brain, and the Mind Must Follow

Could neuromodulation approaches (including TMS, tDCS, neurofeedback, and others) be used to target key nodes in the creativity network? In the future, we may be literally able to put on a headpiece that allows us to enhance the performance of our minds for creativity — the proverbial "thinking cap" taken literally — or for other tasks and performance contexts requiring different kinds of brain activity. Or for entertainment, virtual reality, an immersive, neurally enhanced experience, is within reach. Enjoy playing video games? Even better with neural enhancement.

And what are the implications for neurobioethics? For example, using neuromodulation to convert a non-creative person to a creative person has implications for identity. Many of us organize our sense of self around certain qualities, including "being a creative person." As changing the brain becomes an option, one which we might be able to switch on and off at will, what are the implications for free will and personal identity? Given possibly enhanced creative productions — art, music, literature, architecture, engineering, design, and perhaps new fields we cannot even imagine — culture will feedback as a container for the mind, further influencing the individual engaged in creation.

This research also suggests that we are able to consciously influence ourselves to have greater creativity. Not just by practicing and doing exercises that require creativity or by being creative, but also by using our executive network to invoke our salience network to scan actively for more divergent thoughts, and by disinhibiting our suppression of divergent thoughts. It's easy to train oneself to suppress divergent thinking, and to have a one track mind... but we can unlearn that habit.

A taste of the modeling used in this study:

References

Beaty RE, Kenett YN, Christensen AP, Rosenberg MD, Benedek M, Chen Q, Fink A, Qiu J, Kwapil TR, Kane MJ & Silva PJ. Robust prediction of individual creative ability from brain functional connectivity. PNAS 2018 January, 115 (5) 1087-1092. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1713532115