Autism

Are We Giving Autistic Children PTSD From School?

When we don't understand autistic kids we create a toxic environment for them.

Posted August 31, 2021 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- We must understand the behavior of autistic children to help them.

- Responding without understanding diminishes the personhood, self-esteem and trust of autistic kids.

- Providing an environment sensitive to the needs of autistic students benefits all students.

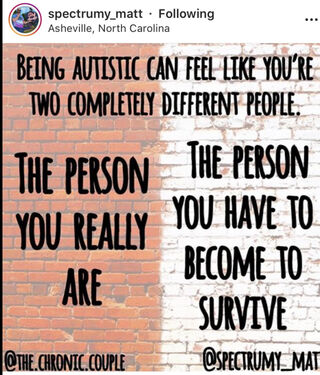

For most autistic children, school can be a toxic environment. Working on the advice of experts, school staff aim to have autistic children’s behavior conform to neurotypical expectations. The more a child is indistinguishable from mainstream peers, the more successful the school intervention is believed to be.

Disruptive or atypical behavior is labeled oppositional, avoidant, attention-seeking, rude, or simply inappropriate. Children who don’t “cooperate” (meaning engage in and respond to school-led, behavioral interventions) are often called non-compliant. The issue is seen to be the child, not the intervention itself. Autistic children are often taught that what they feel, think, or do is wrong and they should do what they are told instead. This can have a life-long impact on self-esteem, self-confidence, and self-advocacy. Quoting a student on a Stanford University panel, “It kills my soul.”

The issue of quashing self-confidence and self-advocacy is worth considering since schools expect students to “participate in post-secondary planning.” According to a 2017 study, “77 percent of autistic high school students play a very limited role or no role at all in post-secondary planning compared to 47 percent of students with intellectual disabilities and 27 percent of students with all other disabilities.” (Gillespie-Lynch, K. et al 2017)

Many interventions treat behavior perceived from the outside, without understanding the meaning or necessity for the child. The behavior is the tip of an iceberg that goes down to sensory, social, emotional, motoric, and cognitive issues the child experiences. A child who is “acting out” may be responding to internal frustration, overstimulation, anxiety, or some other distress. Plans often focus on eliminating the “acting out” behavior instead of recognizing distress. We need to support children, not single-mindedly focus on correcting behavior.

As an example, sometimes autistic children refuse to do work even if they successfully completed a similar assignment before. We assume this issue is attitude and motivation, but attitude and motivation can be very different for children on the spectrum than it is for neurotypical children. Autistic children’s productivity is variable. If children are tired, hungry, not feeling well, or had a problem earlier in the day, they might not be able to access the skills necessary to do an assignment. In a worst-case scenario, this can become a traumatic experience.

This is a slightly altered transcript of an interview with a British autistic adult recalling life in primary school:

I would say, 'I cannot do this. I can't do it.' They put a math worksheet in front of me and said, here, do this. It's like, I can't do it. They try and make me do it, like, just get it over with.

It’s not that I'm being lazy or objectionable. It's not that I don't want to do it. It's that I... I just didn't feel able to do it. Them trying to force the issue would then mean that I got more and more upset and annoyed and angry. At that age, around six or seven, I really didn't express myself well.

I'd just be like, 'No. Piss off, I can't do it!' And then I would get violent. I just struggled and I didn't feel that they were listening to me. I would start throwing things, flip tables over and then the teachers would drag me to my seat.

I would lash out at them and they'd physically restrain me. That was the worst time of my life, when I was in primary school.

It’s likely that if the teacher had allowed the child to do something else or take a break, none of this trauma would have happened. There can be the same failure of understanding in responding to children with sensory or social overload.

The story below is excerpted from a story by Lisa Morgan, an autistic advocate. An autistic student arrived at class finding the desks rearranged.

Standing in the doorway, I tune into the sounds of students talking at different speeds, at different decibels, changing topics with a squeal or two thrown in along with an argument here and there. It’s so hard to think. I panic. There are at least 22 desk chairs squeaking on the floor, pencils being sharpened, the teacher giving directions, students finding new seats. I focus on a spot on the floor, completely overwhelmed. I’m rooted by panic from the change, the noise, and the confusion about where to sit. I can’t find words to explain.

The teacher tells me she wants me to move. Will she touch me? I don’t want to be touched. The teacher warns me again to get ready. I need to move. The teacher’s voice is rising. She sounds angry. Is it me? I’m trying so hard. I move towards a desk, heart pounding, a strong perfume smell making it hard to breathe, a student bumps into me and I stop. My panic rises again. I finally find a desk with my name on it. My head hurts from the smells; I’m overstimulated and overwhelmed, so I sit and rock back and forth to calm myself. The teacher walks over and says, "See how easy that was? Now sit up straight and stop rocking.”

These examples are in the classroom, a relatively “safe,” structured, supervised space. The “no man’s land” of the hallway, recess yard, or cafeteria can be even more problematic.

What can be done? This is taken from a viral Facebook post by a teacher named Karen Blacher in October 2020:

All of my students are neurotypical, but my classroom looks very much like a special education classroom. I teach mindfulness and emotional literacy. I have a calm corner and use it to teach self-regulation. I provide fidgets and sensory toys. My students are thriving. And that made me realize something.

When we treat autistic children the way the world tells us to treat neurotypical children, they suffer. But I have never encountered a child of any age or neurotype who doesn’t thrive when treated like an autistic person should be treated, with open communication, adaptive expectations, and respect for self-advocacy and self-regulation. Maybe neurodiverse people aren’t the only ones who’ve been misunderstood and mistreated all this time. They're just the ones who feel it most.

Accommodations and change are possible and aren’t necessarily expensive. It’s possible to create a sensory or adaptive profile predicting problems and strategies for success. What’s necessary is open-mindedness and willingness to adopt systemic change. The most important thing is to recognize that teaching neurodivergent children in the same manner with which we teach neurotypical children is a recipe for failure, both for the school, and especially for the student.

References

Gillespie-Lynch, K. Bublitz, D., Donnachie, A., Wong, V., Brooks, P. & D'Onofrio J. (2017) For a Long Time Our Voices Have Been Hushed: Using Student Perspectives to Develop Supports for Neurodiverse College Students. Frontiers In Psychology (8) 544