Personality

Why Small Talk, With Almost Anyone, Is So Rewarding

Connection is important, even with people not important to you.

Posted November 30, 2023 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Most people don't look forward to interacting with new people.

- However, most people find that such experiences are more rewarding than they expect.

- Incorporating the beneficial habit of small talk into your life requires practice.

I want to be a warm and friendly person.

But I don’t know how to do it. —David Berman

Several years ago, I was in line at the local co-op when I spotted a fellow patron in an Old 97s t-shirt. To my own surprise, I quietly blurted something as pithy as “Ah, Old 97s” with my trademark awkwardly raised eyebrow.

Mercifully, my half-hearted attempt at human connection landed shockingly well, and the woman who donned the t-shirt and her husband, child, and even parents are now close family friends without whom my life would be much less full. One would think then that I might make it a common practice to form connections based on public claims of shared identity, then, right?

Reader, I do not.

In fact, my friends and I often joke about how out of character that exchange was for me, and how it might explain that I have exactly 7 friends. Like the man in the lyrical allusion above, I’m tantamount to cordial. This is probably the wrong way to live, and psychologists know it.

Meet Gillian Sandstrom. (If you live in a certain area in England, her wholesome and entertaining Twitter account leads me to believe you may already have.) She's a personality and social psychologist at the University of Sussex who has been studying the impact of weak ties—both in the lab and out in the world—for a while.

A weak tie is a transient social connection with someone who is not particularly important in your life, as opposed to strong ties, which are deeper, closer connections. My contact described above turned out to be a weak tie—we actually worked at the same place—and eventually resulted in a strong tie.

But perhaps counterintuitively, weak ties don’t have to become strong in order to positively impact well-being. That’s what Sandstrom and Dunn (2014) found when they asked people to report on their happiness along with the frequency of their weak and strong tie interactions over a period of time. People who engaged in more interactions with the periphery of their social networks tended to report greater happiness on those days.

This can’t be explained away by the fact that extraverts are both more inclined to talk to strangers and more prone to positive emotionality (both true) because people tended to show greater happiness on days where they had more weak-tie interactions compared to their own personal average number of such interactions. Simply engaging with others—even relatively unimportant others—seemed helpful to well-being.

In the same year, Epley and Schroeder conducted a related and now quite renowned study in which they induced commuters to connect with new people on their trip and found that while we largely have limited interest in doing so, we actually often feel better after doing it. The disinclination toward small talk with strangers can stem from anxiety about one’s own abilities as a small-talker or from doubts about the potential benefits of small talk. (I can personally claim both of these anti-motives.) But given that we now have a fair amount of evidence suggesting that engaging in weak-tie or stranger interactions can boost our mood—even for introverts—it may be time to consider how to entice people to act in their own best interest in this regard.

At first blush, it would seem natural that we would be inclined to engage in small talk. The law of effect tells us that if an act is followed by reinforcement, that act is likely to be repeated. It turns out that people may recognize the benefits of engaging with others immediately thereafter, but the effects are transient.

Indeed, Sandstrom and Dunn noted in 2014 that experience-sampling studies like theirs yielded higher numbers of recalled interactions than do typical retrospective studies of social interactions, suggesting the possibility that regardless of positivity, we may simply forget many of our interactions shortly after they occur. Thus it could be that the brief spark of positive emotion fades, and initiating weak-tie interactions does not really get a chance to become codified as a habit.

Thankfully, Sandstrom has some good ideas here, primarily founded on the idea that it takes a critical mass of such behaviors and subsequent reinforcement for the behavior to take hold. Indeed, research indicates that forming a habit intentionally often takes a couple of months (Lally et al., 2010).

In this case, two key possible mechanisms for habit formation can exist. The first involves the aforementioned opportunities for reinforcement: Since many interactions are actually positive, engaging in more of them will strengthen the behavior/response connection. The second mechanism is somewhat opposite and comes in the form of systematic desensitization, wherein people learn that anticipated punishments (e.g., social rejection) do not tend to occur as expected, and thus anxiety is reduced.

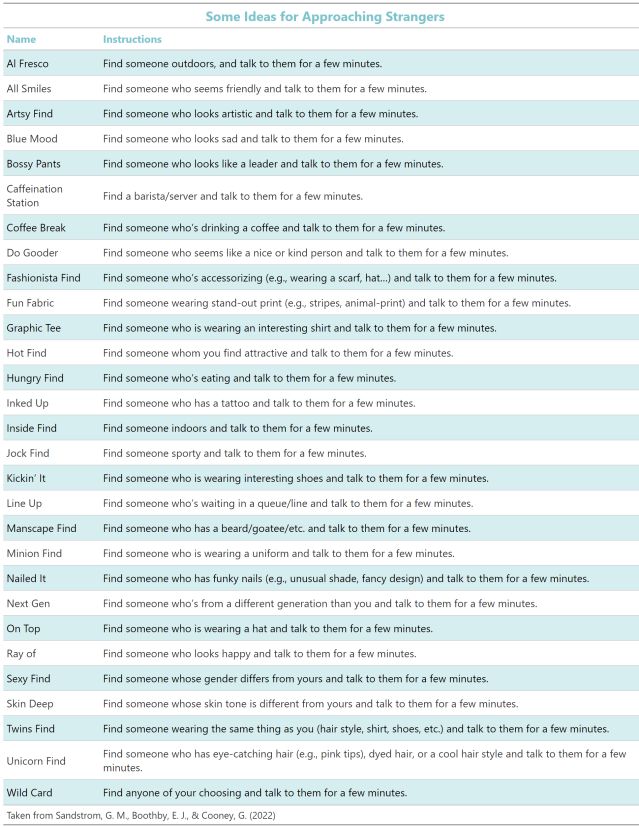

Sandstrom et al. examine both of these possibilities in a recent study. This time, her team gave people “challenges” in which they had to encounter unknown others out in the wild who fit certain parameters, e.g., start a conversation with someone who has interesting shoes or who has a tattoo or who looks sporty.

Here's the full list of 29 possibilities:

Each person was to engage in one activity of their choosing from the list at least once per day for a week. In a control condition, people were asked simply to observe the tattooed individual, whereas, in the experimental condition, they were asked to talk to this person. At the beginning of the study, people in the two conditions reported similar levels of perceived conversational ability, awkwardness talking to strangers, enjoyment of talking to strangers, and positivity of the impression they made on others.

After a week, the treatment group reported significant gains—most of which persisted in a follow-up a week later—in all of these measures: lower awkwardness, and higher everything else. The control group did not show such a pattern. People in the treatment group also reported starting more conversations with strangers in the week that followed the intervention, perhaps because they also reported noticing more opportunities to do so.

Finally—and importantly—people felt less likely to be socially rejected after engaging in the treatment condition. This seemed to be not because they experienced fairly painless rejection but rather because they did not experience much rejection at all. The paper goes into greater detail than I have here, but the results were fairly clear in my reading: Forcing yourself to engage with unknown others can help shift your attitudes regarding the activity, which has the potential to shift behavior, which, as we’ve already learned, is likely to lead to more moments of mundane happiness. Who doesn’t need those?

Coda

As I was working on this piece, we were walking over to my Old 97's friend’s house for dinner when a toddler in a passing car yelled something to my 5-year-old. I was a few steps behind and didn’t hear what she had said: Why did someone just yell at us from a moving car? My wife informed me that they had said, "Hey! I like your tutu!"

I chuckled as I considered the potential response had I taken a similar action, and then I realized that I was succumbing to the standard fallacy that nobody would be glad if I made random social contact with them and that it would likely be a negative experience. But do you know who doesn’t have his misgivings? My 5-year-old. She is constantly approaching weak ties and strangers with some sort of compliment for their dog, their shoes, their hair bow, etc. It makes me a bit sad to think that one day she’ll be more like me, admiring shoes from a distance, quietly to herself.

In the Purple Mountains song referenced at the top of this post, the singer laments his partner making friends and his turning stranger. I’ve definitely become stranger, but we don’t have to. Our assignment this week is to find someone with interesting shoes.

Facebook/LinkedIn image: Drazen Zigic/Shutterstock

References

Epley, N., & Schroeder, J. (2014). Mistakenly seeking solitude. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143, 1980.

Lally, P., Van Jaarsveld, C. H., Potts, H. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 998-1009.

Sandstrom, G. M., & Dunn, E. W. (2014). Social interactions and well-being: The surprising power of weak ties. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40, 910-922.

Sandstrom, G. M., Boothby, E. J., & Cooney, G. (2022). Talking to strangers: A week-long intervention reduces psychological barriers to social connection. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 102, 104356.