Identity

Is Being a Cop (or Anything Else) a Job or an Identity?

The problem of singular identity and what to do about it.

Posted October 25, 2021 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Roles squash the people who fill them. Defining oneself by what one does for work can be alienating and damage one's soul.

- Police officers are at risk for over-identifying with their jobs. This can set them up for disappointment and a sense of feeling betrayed.

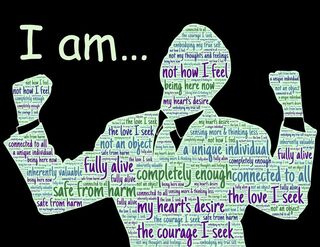

- A person can bolster their sense of self by defining themselves in broader terms.

My colleague, Coach Bruce Sokolove of Field Training Associates, sent me a link to an article by Arthur C. Brooks titled, "A Profession Is Not a Personality." His subtitle? “Reducing yourself to any single characteristic, whether it be your title or your job performance, is a deeply damaging act.” I couldn’t agree more.

I’ve met many cops over years of practicing police psychology who proudly declared, “Being a cop is not just a job; it’s an identity, it’s who I am.” While this may be an expression of loyalty and pride at being part of an elite group, it is also a setup for disaster.

Kevin Gilmartin, police psychologist, retired sheriff’s deputy, and author of the widely read book Emotional Survival for Law Enforcement says that over-identifying with work and linking one’s sense of self to the job is risky business. Risky because you are putting all your eggs into the one basket over which you have little or no control. Think about it. Do you control your chief? The board of supervisors? The city council? Your local politicians?

If we are not careful, our professional roles will squash us. To be a cop 24 hours a day will wear you down and alienate everyone who is close to you. (Ditto for being a therapist 24/7.) We all have multiple roles in life. We are parents, children, siblings, friends. We are athletes, artists, mechanics, volunteers, gardeners, spiritual and religious beings. To tie your entire identity to your profession sets you up for a lifetime of striving followed by the inevitable professional decline and disappointment.

I’ve said this before: While there are good people in organizations, there are no good organizations. Organizations exist for their own survival. They aren’t interested in you as an individual. Your blue family, the one that promised to always have your back, is notoriously fickle. Sociologist Egon Bittner was one of the first to look at police work from an academic perspective. He described police officers as interchangeable pieces of labor, used to fill holes in the system, not work to their individual strengths or preferences.

I was treating Officer K. for post-traumatic stress following a fatal shooting. K. was a committed cop who never wanted to do anything else. The job was his life, leading to a couple of divorces. I doubt K. ever read Bittner’s book. He didn’t have to; he was living it. He described himself as a “tool, no different from the bumper on a car.” From his perspective, when the bumper fell off after the shooting, they sent him to me to put it back on. Not because they cared about him, but so they could send him back to the field ASAP.

Are you over-identifying with your job? Paraphrasing Arthur Brooks, ask yourself the following questions.

- Is my job the biggest part of my identity? Is it the way I introduce myself or, even more damaging, understand myself?

- Am I sacrificing love relationships for work? Have I rejected romance, friendship, or family because of my career?

- Do I have trouble imagining being happy if I were to lose my job or career? Does the idea of losing it feel a little like death?

Did you answer yes to any of the above? I’ve paraphrased Brooks’ suggestions for changing.

- Take a break, find a way to get some time off, reduce your overtime. See how you feel. Get some perspective. Make your own Sabbath where you don’t work and dedicate all your actions to relationships and leisure. Spend time with people who have no connection to your work.

- Quit hanging out with other cops who only want to talk about work. Spouses complain no one wants to talk to them at parties. Don’t let this happen. They are as important as you are. Quit trying to be special. Stop reducing yourself to a single quality. Or, as Brooks says, you will turn yourself into “a cog in a machine of your own making.”

I’m going to close with a quote from Coach Bruce Sokolove, the colleague who sent me the Brooks article. He’s trained hundreds of field training officers over many years. This is the message he pounds home whenever he gets the chance:

“I see so many (one is too many) cops who define themselves by their professional choice. Never stop hitting the reset button to remind young Blues that you never confuse what you do for who you are. Love your occupation but don’t fall in love with The House.”

References

Brooks, Arthur C. (September 30, 2021) A Profession is Not a Personality. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2021/09/self-objectification…

Bittner, Egon (1979) The Functions of the Police in Modern Society. Boston. Oelgeschlager, Gunn & Hain.

Gilmartin, Kevin (2021) Emotional Survival for Law Enforcement (revised edition), Tucson. ESpress.