Testosterone

When It Comes to Color, Men & Women Aren't Seeing Eye to Eye

How does the brain's wiring affect men and women's perception of color?

Posted April 8, 2015 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- Three dimensions affect how we visualize color: hue, saturation, and brightness.

- Research suggests that the wiring differences in visual areas of the brain contribute to how men and women see differently.

- Differences in testosterone levels promote drastically different organization of the neurons in the visual cortex in men and women.

This guest blog post was written by Sadie Steffens.

The paint color in our master bathroom has been a source of debate since we bought our house. While I am certain that the color is firmly in the purple part of the spectrum, my husband insists that the paint is blue. Period.

Visiting friends have often been asked to weigh in on this debate, and the outcome is fascinatingly similar every time. When asking couples to cast their votes, men instantly declare the color to be blue. Women, on the other hand, typically pause before suggesting something like “periwinkle” or “lavender blue.”

This phenomenon has been played out between men and women time and time again—from selecting clothing to disagreeing at the paint store about whether one hue of blue looks more purple than another. Although you may be tempted to write off this difference as a consequence of cultural conditioning, the true root is physiological.

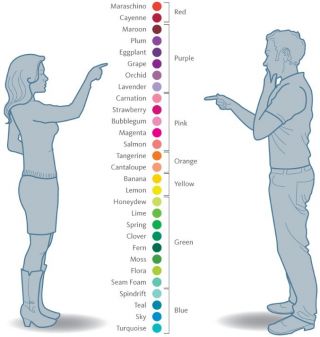

Previous research has shown that women have a larger color vocabulary—think periwinkle, azure, and other color names that are unlikely to be used by men in general conversation. But is this lack of color names the main reason why men and women “see” color differently?

Israel Abramov, a behavioral neuroscientist at CUNY’s Brooklyn College, doesn’t think so. He’s curious about how the wiring in the brain influences our perception of color. Do variations in neural connections explain perceptual differences between men and women?

Three dimensions affect how we visualize color: hue, saturation, and brightness. Hue is the actual color—red, yellow, green, or blue. Saturation is the deepness of the color: emerald green is more saturated than pastel green. Brightness describes the way a color radiates or reflects light.

Abramov asked men and women to break down the hue of a color and to assign a percentage to the categories red, yellow, green, and blue. The results showed that women were more adept at distinguishing between subtle gradations than were men. This sensitivity was most evident in the middle of the color spectrum. With hues that were mainly yellow or green, women were able to distinguish tiny differences between colors that looked identical to men. In fact, Abramov found that slightly longer wavelengths of light were required for men to see the same hues as women—hues identified as orange by women were seen as more yellow by men.

However, when shown light and dark bars flickering on a screen, men were better than women at seeing the bars. Men were better able to perceive changes in brightness across space, a skill useful for reading a letter on an eye chart or recognizing a face. This effect was increased as the bars narrowed, suggesting that men are more sensitive to fine details and rapid movement than women.

These results suggest that the wiring differences in visual areas of the brain contribute to how men and women see differently, regardless of whether a person has an extensive vocabulary of color names. Sensory differences between sexes have been well studied. In the realms of hearing, smell, and taste, women perform better than men at distinguishing between slight differences. Hormone levels may be the basis for these sex differences.

Abramov believes that testosterone expression early in development plays a major role. Differences in testosterone levels promote drastically different organization of the neurons in the visual cortex in men and women. There are more receptors for testosterone in the cerebral cortex (the part of the brain that processes information from the senses) than there are in regions of the brain associated with reproduction.

Men have more testosterone receptors than women, especially in the visual region of the cerebral cortex. The elements of vision that were measured in this study are determined by inputs from these specific sets of neurons in the primary visual cortex, so it makes sense that different numbers of receptors would result in differences in visual perception.

But why do men and women perceive color differently? One potential explanation goes all the way back to the hunter-gatherer responsibilities of early nomadic tribes. As hunters, men needed to be able to distinguish between predators and prey from afar. On the other hand, women might have developed better close-range vision from the act of foraging and gathering.

Although further research is necessary, these visual differences could have consequences for how men and women perform at tasks such as art and athletics, where differences in near-vision and far-vision could be important.

Regardless, we can be sure that the way we visualize color is somewhat different from person to person, as evidenced by “the dress” that recently sparked much debate on the internet. (I’ll admit, I was a misguided member of team #whiteandgold).

My husband and I are picking out colors for our guest room now. Although we disagree about whether the blue we chose is more green or more grey, at least we were both able to agree when we found the right color.